If last year’s headlines are any indication, incidents of strange and aggressive animal behavior are on the rise in North America. Experts attribute increasing human-animal encounters to a combination of factors—from human encroachment into once–remote wildlife habitat to an ever-increasing number of carnivores migrating into America’s cities and suburbs in search of an easy meal.

While recent statistics from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show you have a better chance of getting killed or seriously injured by hitting a whitetail deer with your car (the cause of roughly 130 deaths in the U.S. every year) than in an animal attack, these compelling stories from 2013 show that you can never get complacent when you step outdoors.

In each of these stories, the victim managed to survive through a combination of quick thinking and good luck. Our panel of animal-attack experts examines the likely causes of the vicious encounters, what can be learned from them, and how each might have been avoided.

The Experts:

Dave Smith: Dave Smith is a naturalist who has worked in Yellowstone, Glacier, Denali, and Glacier Bay national parks. He is the author of several books, including Don’t Get Eaten: The Dangers of Animals That Charge and Attack.

Kathy Etling: One of the nation’s most respected authorities on bear biology and behavior, Kathy Etling is the author of the two-volume series Bear Attacks: Classic Tales of Dangerous North American Bears.

Mike Lapinski: Mike Lapinski is the author of 11 outdoor books, including True Stories of Bear Attacks: Who Survived and Why; Wilderness Predators of the Rockies; and Death in the Grizzly Maze: The Timothy Treadwell Story.

1. Turkey Hunter Calls in Wrong Tom

Photo by Mark Miller/Images on the Wildside

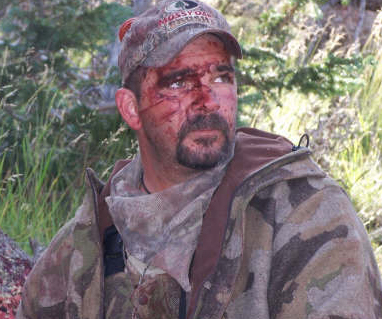

Bud Griffith was hunting turkeys in the woods of his Lincoln County, Kentucky, farm last April when he was attacked by a 30-pound bobcat, according to a report in the Central Kentucky News.

“I was sitting there with my back against the trees,” Griffith told the paper. Scratching out a few yelps on his call just a few yards from his decoys, Griffith felt an animal suddenly jump on his left shoulder, reach around his face, and smack him in the right eye. The bobcat immediately tried to escape, and Griffith, feeling blood running down his face, instinctively fired and killed the animal.

“If I hadn’t had my glasses on, I think he would have taken out my eye,” he said.

Smith: Clearly the cat saw the decoys, saw the movement of the hunter, and pounced, fully expecting a turkey to be there. Short of giving up hunting, I don’t see how this encounter could be avoided. Shooting the bobcat was a good idea, so authorities could test it for rabies.

Lapinski: Anyone who hunts and calls to turkeys long enough will eventually be stalked by a coyote. But sometimes there are other predators out there. Whenever you hunt turkeys or anything from a stationary position on the ground, you have to be prepared and set up in such a way that allows you to see what may be sneaking up on you. Eye protection isn’t something many hunters think about, but Griffith’s glasses probably saved his eye.

Quick Attack Fact: Bobcats rarely attack people without provocation, but those that do typically display symptoms of rabies.

2. Black Bear Mauls Canadian Man After Killing His Dog

Photo by Tony Bynum

While enjoying a morning cup of coffee on the porch of his northern Ontario cabin, Joe Azougar thought he heard thunder but turned to see a black bear barreling at him.

His dog, a 6-month-old German shepherd, leaped into its path, giving Azougar time to get indoors. The man later told reporters he locked the door, called a friend (who dialed 911), and then looked out a small window to see the bear dragging the dog’s lifeless body into the nearby bushes.

A minute later, the 300-plus-pound bear returned, smashed a window with its paw, and began forcing itself inside the tiny cabin. Azougar threw things at the animal and stood on a chair “to appear large.” But, ignoring Azougar’s shouts and screams, the bear climbed halfway through the busted window frame before a panicked Azougar decided his best chance for escape was to run.

He almost made it to the road before the bear caught up with him. Azougar later described the feeling of being scalped as the bear’s teeth tore at his skull, then ripped at his neck and shoulder. The attack continued until Azougar, nearly unconscious, felt the animal dragging his body toward a nearby ditch. The bear likely would have finished him off had it not been for two women who happened by and honked the horn of their van, frightening the bear away.

Reattaching Azougar’s scalp required some 300 stitches. The bear was later killed, but tests conducted by the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources failed to reveal a disease or abnormality that might explain the predatory attack.

Smith: My guess is that garbage and unnatural foods—reports mentioned that Azougar kept animals—might have been a factor in the bear’s approaching. Bears love dog food, oats for horses, chicken feed, etc. Any time food or garbage isn’t securely stored, it’s likely to attract them. Whatever the bear’s motivation, this was clearly a predatory incident, which means you fight back any way you can.

You should never run from a bear unless you’re running for shelter and you’re confident you can reach it before the bear does. So initially Azougar made the right move by dashing into his cabin. Once inside, the first thing he should have done was grab a weapon for self-defense. Did he have a firearm? How about an ax, knife, or fire extinguisher? The best time to fight the bear would have been when it was coming through the window.

I don’t blame Azougar for running—the cabin he was in was reportedly very small. But with nothing outside to run to and no hope of outrunning the bear, going outside was a big mistake. He did, however, do the right thing by trying to fight back. Unfortunately for Azougar, this had little effect on the predatory bear.

Etling: The bear charged the man and his dog on the porch of the cabin, fought with and killed the dog, and, thus, had a meal. But, for no reason that I can discern, the bear left the dog’s carcass and attempted to enter the cabin and attack the man. This is such aberrant behavior that it defies explanation.

Trying to appear large in the face of an ongoing attack is pointless. But had Azougar smacked the bear in the face with, say, a cast-iron pan as it was sticking its head in the window, the rest of the attack might have been averted.

Then again, if it were my cabin, I would have had a gun someplace nearby for protection. My first instinct would have been to shoot the bear.

Quick Attack Fact: In a 2008 study of Alaskan bear attacks, bear spray stopped undesirable black bear behavior 90 percent of the time during close-range encounters.

3. Utah Sheepherder Gored by Wild Wapiti

Photo by Denver Bryan/Images on the Wildside

The Salt Lake Tribune reported last October that Utah wildlife officials who had been relocating mountain goats in the La Sal Mountains east of Moab were approached by a man frantically speaking Spanish, claiming an elk had attacked his friend.

Three hundred yards away, officials found Hugo Macha covered in blood and suffering from a severe wound to his back, a punctured lung, and other injuries. Macha, a remote mountain sheepherder, told officials that he was sitting against a tree and watching his flock when a bull elk suddenly emerged from the forest and approached him. Macha tried to move away, but the bull ran him down and gored him with its antlers until the sheepherder was unconscious. Macha, who was airlifted to a local hospital, said later that by the time he regained consciousness, the bull had vanished.

Smith: This guy was a real toughie, but trying to get away was a mistake. Standing your ground is always a better strategy. The message that sends, even if you pee your pants, is, “If you attack me you might get hurt in the process, too.” Rutting bull elk can get feisty, and about the only thing Macha might have done to prevent this attack would have been to stand up, shout, and let the animal know he was not a rival elk. Or, if possible, climb a tree.

Lapinski: I’ve been treed by rutting bull elk about 12 times when photographing them. I would have to say that the man’s inexperience with the situation he suddenly found himself in was the biggest reason why he was attacked.

If waving your arms and shouting at the animal doesn’t work, walk—don’t run—to a tree and either climb it or simply put it between you and the animal until it loses interest in you and walks away. One thing you never do is turn your back and run away. It triggers an aggressive response to chase, even in elk.

Quick Attack Fact: A wildlife photographer taking pictures in Yellowstone National Park in October 2012 observed a single bull elk damage nearly four dozen vehicles.

4. Idaho Grizzly Researcher Attacked

Photo by Tim Irvin/Images on the Wildside

The Jackson Hole News & Guide reported last July that Brett Panting, a wildlife technician conducting habitat research for the nonprofit Wildlife Conservation Society, was attacked by a radio-collared grizzly in the Caribou-Targhee National Forest west of Yellowstone National Park. Panting was reportedly carrying bear spray but was unable to deploy it in the dense, brushy habitat where he was working.

After biting the man, the bear bolted from the scene, according to the newspaper story. Panting’s colleagues were in the vicinity, and the man was taken to Idaho Falls Hospital, where he received treatment and minor surgery for puncture wounds and lacerations.

Smith: This story illustrates that attacks can happen to anyone, no matter how woods-wise or bear-savvy you happen to be. The best advice is to simply avoid areas with limited visibility where you think bears might be present. Make some noise, pay attention, and be ready.

Carry a firearm or bear spray, and if you become aware of a bear, immediately get your gun or spray in your hand. I’ve done the math, and when a grizzly charges it can cover about 44 feet per second—like it’s been shot out of a cannon. If you don’t react within two seconds, you’re toast.

Etling: Here, the wildlife technician seemingly ventured alone into dense undergrowth where grizzlies were known to be active. The story mentions other people on the scene, but any time you’re conducting grizzly habitat research, a minimum of two people should be dispatched, one of whom should be on guard while the other technician conducts his work.

Quick Attack Fact: If you find yourself in an up-close encounter with a grizzly bear and it yawns, the bear isn’t bored. “Yawning” is actually a sign of stress.

5) Colorado Man Attacked by Trio of Coyotes

Photo by Tim Christie

A resident of suburban Boulder County, Colorado, Andrew Dickehage, was walking to work with a flashlight in predawn darkness last October when he thought he heard “a bunny rustling” in a bush.

Pointing his flashlight toward the noise, he was immediately hit by a large coyote that sank its teeth into his hand and fingers and wouldn’t let go. After beating back the coyote with his flashlight, Dickehage was set upon by two more.

“They were continuously jumping on me, one after the other,” Dickehage told a reporter for the Longmont Times-Call. “It was so dark all I could see was the glimmer of their eyes.”

According to news reports, the coyotes continued their attack—biting, scratching, and lunging at Dickehage—for more than a minute along a 70-yard stretch of road. While fighting them off with his flashlight, the man sustained numerous bites and puncture wounds to his arms, hands, and face. Two of the coyotes, which wildlife officials did not believe were defending their young or a food source, were later killed and found to be in good health.

Smith: Whoever makes that flashlight should put this guy in an ad. Since this took place in a residential area, it’s a good example of how animals that are used to humans can become emboldened. This guy was fighting for his life, and he did a great job using the only weapon at hand. Even if he had had mace or bear spray, it doesn’t sound like there would have been time to deploy it in this situation.

Etling: This is abnormal coyote behavior, but it shows that even in the suburbs they can be dangerous predators. This strikes me as an opportunistic attack. The coyotes saw Dickehage as prey, maybe felt empowered because they were in a pack, and just went for it. The man is lucky to be alive and did the right thing by using his flashlight as a weapon.

Quick Attack Fact: A study of 108 coyote attacks from 1960 to 2006 revealed 37 percent of those attacks were of a predatory nature.

6) Man Thwarts Bear Attack by Grabbing Bruin’s Tongue

Photo by Donald M. Jones

Out for a walk on his wooded property last October, Gilles Cyr of Grand Falls, New Brunswick, suddenly saw a blur of something black come flying out of the woods at him.

“For a second, I thought I was dead,” Cyr told reporters. The black bear knocked Cyr down and was immediately on top of him. “His mouth was wide open right in front of my face, so the last thing I remember I had his tongue in my hand and didn’t want to let go.”

Cyr said he grabbed the bear’s tongue on instinct and held on tight so that if the animal tried to bite, it would also bite its own tongue. Managing to get out from under the bear and escape the initial attack, Cyr let go and ran behind a nearby tree.

The bear followed him but then suddenly appeared to lose interest before walking away. Cyr received only superficial wounds in the attack.

Smith: When I worked in Yellowstone, I read about a similar tussle in which a guide escaped a bear attack by grabbing the animal’s tongue, but I certainly wouldn’t recommend it as a go-to move. Usually in a predatory attack like this one, the bear will not break off the attack until you’re dead, so the results of this encounter are pretty unusual. The guy survived by fighting back, so it’s hard to say what he could have done differently.

Etling: This is the worst possible scenario: an unavoidable, predatory attack by a black bear hell-bent on eating a human.

Cyr could have waited to go hiking with someone, but he was on his own property and probably felt safe. He was totally surprised and wouldn’t have had time to deploy bear spray even if he had been carrying it. Cyr was knocked flat, but in fighting back—holding onto the bear’s tongue and causing the bear to hurt itself every time it tried to hurt Cyr—he did everything right.

Quick Attack Fact: Human food or garbage was present in 38 percent of fatal black bear attacks between 1900 and 2009, according to a 2011 study. The bear either showed interest in the food or actually consumed it.

Correction: This article originally misstated the name of the Wildlife Conservation Society researcher as Brent Panting.