We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

Hunters love to sit around the fire and argue about guns. When there’s no fire, there’s still social media, where people also sometimes argue. When I saw Freel and Towsley engaged in a Facebook pissing match over bear-defense handguns, I invited them to bring it to the pages of Outdoor Life. Enjoy. —Will Brantley

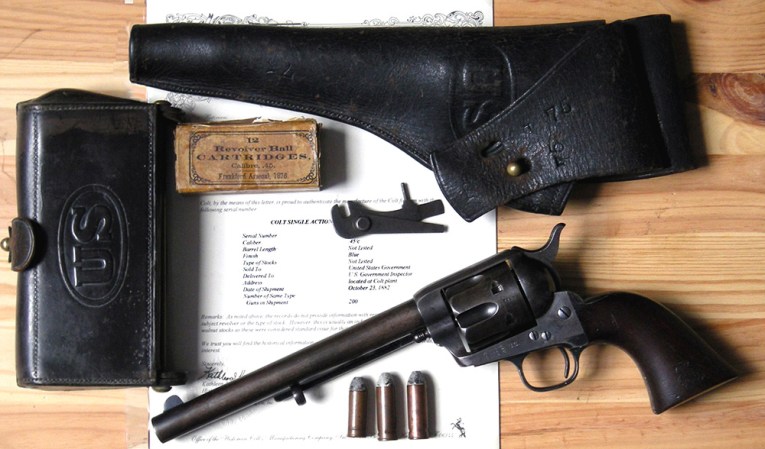

Wheelguns for Bear Defense

I’ve been hunting bears for 40-some-odd years all over North America and in Russia. I have learned a couple of truths. First, bears are tough, both in construction and attitude. They have thick hides, strong muscles, and big bones. When wounded, they rarely give up quickly.

The idea of using a semi-auto handgun in a cartridge designed for self-defense against humans is ballistic folly. I know everybody thinks they are going to go John Wick on a bear and overwhelm him with a multitude of bullets, but that ignores the second bear truth: Bear attacks happen very fast. You may get one or two shots, if you are lucky, before he is chewing on your skull like an hors d’oeuvre.

True bear-protection handguns use a big bullet with lots of horsepower behind it to get through the hide and muscle, and to break bones. Big-bore revolvers with heavy-for-caliber, flat-nosed, non-expanding bullets do that very well. Cartridges designed for defense against human predators do not.

The 10mm auto with the best 220-grain hard-cast bullet has a pathetic 703 foot-pounds of energy. In contrast, a .500 Smith & Wesson with a 440-grain bullet has 2,579 foot-pounds of energy. That’s double the bullet weight, 25 percent more bullet diameter, and 267 percent more energy (not to mention 170 percent more momentum, which many believe is a better measure of a bullet’s ability to penetrate than kinetic energy).

Semi-autos can jam. Revolvers rarely malfunction, and there is no magazine to fall out, as apparently happened during a fatal attack last fall on a Wyoming guide.

Another guy in New Mexico failed to stop a black bear quickly enough with his 10mm, even with multiple hits. The bear was gnawing on him when he tried a head shot. The gun jammed. He cleared the jam while the bear continued to dine on his leg and finally killed the bruin. Rescuers had to cut the bear’s jaws off his leg.

Contrast that with my friend, Alaska resident and guide Lucas Clark. A large brown bear attacked him. He shot it with his .500 S&W, and the bear fell down and politely died.

Little-gun advocates have two arguments. One is for fast follow-up shots. It’s that John Wick syndrome again. But a revolver is just as fast as any other handgun for the first shot, and that’s the one that really counts. They are fast for follow-up shots too, even the big boomers. I can put five full-power shots from my .454 Casull single action on target in 2.8 seconds. I have video to prove it.

What’s the second little-gun argument? Proponents claim that most people can’t shoot a big gun. The recoil melts snowflakes or something. Anybody who can shoot a 10mm can very quickly learn to shoot a grown-up cartridge. I know because I have taught dozens.

This is your life we are discussing. What would you rather have in your hands when a 1,200-pound brown bear is directing his anger issues at you? ––Bryce M. Towsley,

Auto Pistols for Backcountry Protection

Nothing is certain in a bear attack. I’ve lived in Alaska my entire life, and I have killed and seen killed in the range of 45 black bears and 16 grizzlies and brown bears. Each bear is different, but typically, if one gets amped up, it’s painfully difficult to stop it.

If you’re in a bear attack, you’ll be wishing for a rifle. A big one. A handgun is better than nothing, but whether it’s a 9mm or .500 S&W, it’s just punching holes. Some punch bigger holes, and some can punch deeper ones. But they all lack the trauma-inflicting velocity of a rifle. For perspective, an 8-inch .500 with a 440-grain bullet tops out with less muzzle energy than a .308. A brain shot is pretty much the only way to guarantee that you’ll stop an attacking bear with any handgun. Something you can shoot quickly and accurately, and fire as many rounds on target with is a must. (And good luck taking follow-up shots with a single-action that kicks like a .454.)

But a gun’s worthless if it isn’t with you. Ease of carry and use are, in my opinion, more important than caliber. A Ruger Super Redhawk in .454 Casull will weigh more than 4 pounds loaded. A Glock 20 loaded with 15 rounds is just 2.5 pounds.

Read Next: An Expert’s Guide on How to Stay Alive in Grizzly Bear Country

Many of us here in Alaska have quit carrying giant hog legs because, frankly, they’re a pain in the ass. But if you don’t carry it, it’s useless. The light weight, ergonomics, and increased capacity of a 10mm auto is something to take seriously. So is the potential for practice. Big revolvers vary from unpleasant to painful to shoot, and ammunition for them is too expensive for frequent practice for most people. The 10mm auto is stout, but recoil is manageable. You can find practice ammo for about $20 a box. Just be sure to switch to hard-cast or solid bullets for defense.

Some use this incident as an argument against the 10mm, but last summer, when a fellow from New Mexico put the final bullet through the head of a black bear that was clamped on his leg, he had already spent more than six rounds. His initial body hits with personal-defense ammo may not have stopped the attack, but it’s difficult to say whether better bullets or a larger handgun would’ve either. Ultimately, his gun was with him, the bear is dead, and he is alive. Bear attacks aren’t always as neat and clean as we imagine. Sometimes the bear bites you, and that’s going to hurt—but if you survive the attack, it’s a win.

Having a handgun that you can shoot comfortably, practice with regularly, and carry at all times will do more for your odds against a bear than a giant revolver that you might shoot a couple of times per year—and that’s so heavy that it’s stuffed into your backpack or left sitting behind in the truck anyway. ––Tyler Freel

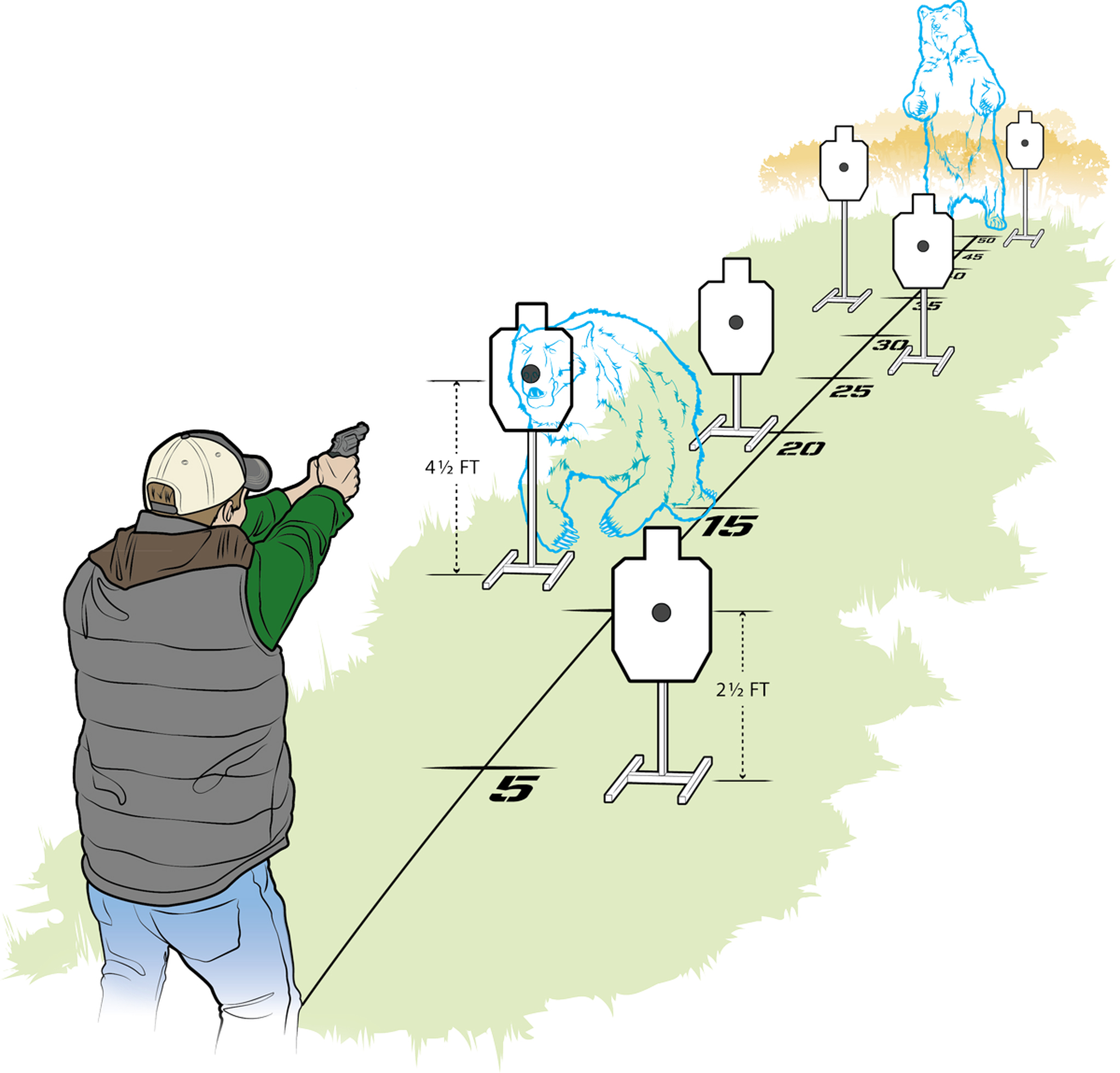

A Practice Drill to Drop a Charging Grizzly

No matter what gun you decide to carry in the backcountry for bear protection, practice taking down a charging animal in a do-or-die situation.

Of all the animals in North America, the one most likely to charge and attack is the brown bear. I live and hunt in grizzly country and always carry bear spray and a sidearm with me when I venture past the trailhead. (In case you’re wondering, my handgun of choice is a Smith & Wesson 329 PD .44 loaded with 420-grain hard-cast bullets.)

Bear charges happen fast and in close quarters. Your shooting needs to be spot-on in order to stop the threat. This drill will test your speed and ability to transition between targets rapidly. You can perform this with a handgun, a rifle, or a shotgun.

Setup the Bear Drill

Set up four to six targets in a staggered pattern, placing the farthest 50 feet downrange and the closest at 5 feet. Also, alter the height at which you position the targets, placing them between 2 ½ to 4 ½ feet above the ground.

You can use IPSC targets or cut out 8-inch circles of cardboard. In either case, put a 2 ½-inch black spot in the center of the target. (This is the bear’s nose, a useful aiming point.)

How to Shoot The Drill

Move your eyes ahead of your gun and learn to time your shot so the trigger breaks the moment your front sight settles on the black dot. Don’t start and stop the gun in a jerking motion— keep it moving smoothly.

Use a shot timer (you can download one for free to your smartphone) and start with your firearm at the low ready. Set the timer for 3 seconds. At the sound of the buzzer, bring the gun up to the farthest target and take a sight picture. Whether you pull the trigger is up to you, but either way, quickly transition to the next target and then the next. Keep the gun moving in a smooth back-and-forth motion. Before the 3 seconds are up, you should have taken a sight picture on each target, finishing on the closest one.

One clean hit is better than a bunch of misses, but if you’re using a handgun, you want to try to get at least three good hits in that time frame—though the more, the merrier. ––John B. Snow