Autumn Veatch had given up.

She had just endured a frigid and painful night alone in the North Cascades without shelter, dry clothing, fire, food, or first-aid. No one knew where she was—herself included. She had blistering second-degree burns on her dominant hand, and her body was bruised and sore. The day before, she’d watched her step-grandparents die.

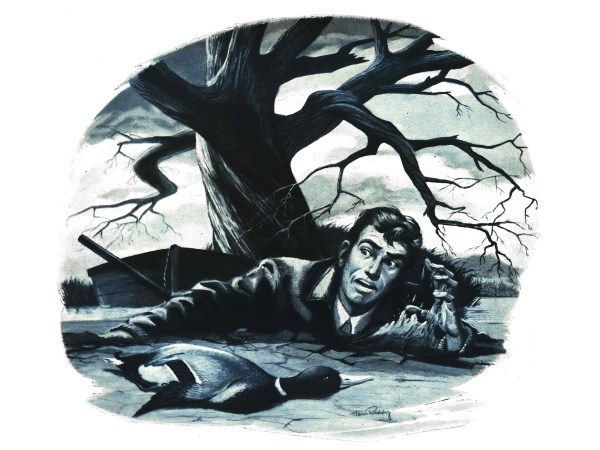

So the 16-year-old curled up on the damp earth at the base of a conifer tree. It seemed as good a place as any, she decided. This is where she would die.

FLIGHT LOG

Some 20 hours earlier, Veatch had climbed into her step-grandparents’ prop plane in Kalispell, Mont. It was Saturday, July 11, 2015. Although the family originally planned to drive Veatch home to Bellingham, Wash., her step-grandfather, Leland Bowman, offered to fly her instead.

Inclement weather delayed their early-morning departure, but when they realized it wouldn’t improve further, the Beechcraft A35 lifted wheels at 1:01 p.m. P.T. Leland and Sharon Bowman manned the cockpit while Veatch texted her boyfriend from the backseat. He would be waiting at the airport in Lynden, Wash.

The trio flew along under the clouds until, about 90 minutes into the flight, fog engulfed the plane. Everything turned white.

They almost crashed once, but Leland swerved and narrowly missed a mountain. Instinctively hunching over in her seat, a panicking Veatch kept her mouth shut and listened to Leland and Sharon, who Veatch says kept their cool—until the GPS shut off. The couple had been navigating with a tablet (similar to an iPad) and cell service. But the signal cut out. Now they were flying blind.

According to WSDOT, the aircraft dropped off radar at 3:21 p.m. P.T. The last cell signal from its occupants vanished at 3:49 p.m.

IMPACT

The plane’s belly scraped trees. There was no whiplash yet—the crash unfolded almost gradually. They skidded along, mowing down pines and firs until the propeller-tipped nose struck the ground. Veatch says she was fully conscious for the whole ordeal, but she can’t recall exiting the cabin. The plane was already on fire when she slipped outside. Meanwhile, the Bowmans were still alive. She knew because she could hear them screaming.

Veatch tried to pull Leland, who was closest to the door, from the cockpit. She told him to unbuckle his seatbelt, but he was concussed and disoriented. The heat burned her right hand, driving her back. She tried again, but the flames were too much. Veatch’s face was already burned, her hair scorched, and her eyelashes shriveled. Soon the yelling stopped, and Veatch knew it was over. So she ran.

“The smell of burning flesh is really unpleasant, and it was hurting my heart,” Veatch says. “So I started going downhill. I was—what’s the word—just full of adrenaline, and not really present.”

Sobbing, almost yelling, Veatch slid down the steep slope, choosing that direction simply because it was the easiest way out. The plane’s severed wing lay tangled in pines, and an explosion reverberated behind her. She stumbled down the mountain, grabbing branches and bark with her blistered hand, lurching from tree to tree as she descended.

“I ended up tumbling over the side of a cliff. It wasn’t a really big one, but it was enough for me to fall on my back. At that point, I was like, Okay, I need to think for a second.“

Veatch recalled the survival shows she had watched with her dad in grade school—shows like Man vs. Wild and Dual Survival. The two main principles she remembered were to travel downhill and follow water. Listening intently, Veatch thought she heard the faint sound of a freeway. It turned out to be running water.

DOUSED

Everything was wet. The clouds were spitting, the ground was saturated, and Veatch was drenched.

She had been following the rivulet for hours, watching it grow wider and deeper, and crossing it repeatedly when the bank became impassable. The afternoon turned to evening, and Veatch was still sobbing loudly—freaking out, as she puts it—and talking aloud.

The death of the Bowmans had rattled her, Veatch says, but the enormity of the situation also weighed heavily. That night she climbed onto a ledge above the river to sleep. It wasn’t dry, but it was the closest patch of habitable ground. She wasn’t worried about wild animals, like snakes or bears. Instead her mind was occupied by a single thought: I’m gonna die.

Hypothermia would be the culprit. She realized then that it had been a poor choice to continuously cross the creek, but there was nothing to be done about it now. By the end of the night, her chilled cotton clothes and canvas Chuck Taylor sneakers lay in a pile. Still wearing a tank top, Veatch wrapped her cardigan around herself, exhaling into the cocoon to stay warm. Sleep was nearly impossible, especially with the pain from her burned hand. But it was rest.

Come first light, she put on the wet clothes and resumed the march, feeling worse than she had the day before. After nearly an hour, any hope that remained had drained away. So 16-year-old Autumn Veatch—lost, uncertain, ill equipped, and alone—lay down against the big conifer to die.

Only she couldn’t.

SELF RESCUE

She kept imagining the sound of a helicopter, but nothing was there. After 45 minutes of searching the sky and then lying back down, she rose a final time.

“Somehow I got motivation. I was angry. I was like, This isn’t fair. How come I have to die right now? I have so many things that I want to do.”

The rest of the day followed much as the previous one had, with zigzagging river crossings and endless trudging. She did end up spotting rescue aircraft but couldn’t attract their attention. Morale waxed and waned.

As the adrenaline faded and tedium set in, she kept her mind occupied. Veatch describes herself as quiet, and had remained so for much of the hike. But now she sang songs and told the story of her trek aloud—just to hear how crazy it sounded. She wondered if she was on the news. She wondered what her boyfriend and family were thinking. Random thoughts popped into her head, including scenes from children’s movies and long-forgotten classmates. She even tried prayer.

“I did pray, if we’re being honest here,” says Veatch, who is agnostic. “I felt alone. When you’re that alone and probably going to die, might as well pal up to the big man.”

That night was worse than the first. She slept along the river and was tormented by sand fleas. Walking the next morning hurt. Her muscles were stiff and sore from exertion and dehydration, her skin itchy and chafing from the insect bites and sand in her clothes.

Today, though, spirits were high: survival seemed certain. Surely two days of walking had brought her close to civilization.

At last, a wooden bridge materialized amid the trees. She thought she was hallucinating, but the vision held her weight and Veatch followed its path to a trailhead parking lot.

REENTRY

For an hour, motorists zoomed past the disheveled girl waving frantically from the highway shoulder. It was Monday, July 13—two full days after the plane had gone missing. Veatch knows she “looked like Freddy Krueger” at that point, but says she was clearly distressed and still nobody stopped. People even waved.

Unable to stand anymore, she returned to wait for the owner of the single car parked in the lot. To add insult to injury, the trailhead marker there read “Easy Pass.” Thirty minutes later, a car pulled into the lot. Veatch started crying.

The Good Samaritans provided Gatorade and a ride to the town of Mazama, where she made a 911 call that would later go viral. Listeners criticized her for her lack of emotion, but Veatch had already done her weeping on the mountain.

“Autumn Veatch…V-E-A-T-C-H,” she told the dispatcher. “We crashed, and I was the only one that made it out.”

READ MORE

Alone, severely injured, and 10 miles into Idaho backcountry, elk hunter John Sain had a decision to make: end the suffering or crawl for help Vincent Soyez