What is the Bear Matrix? It’s a world of horrific maulings, canine teeth gnawing on scalps, claws ripping into flesh and people being eaten. No, this isn’t a nightmare-it’s a computer database compiling info on more than 500 bear attacks that have occurred in Alaska since the early 1900s.

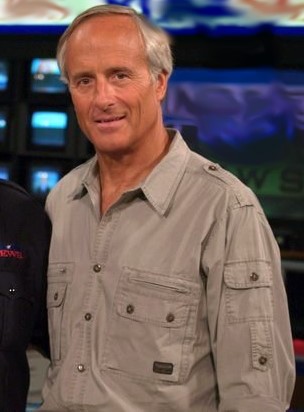

The gatekeeper of this data is U.S. Geological Survey research biologist Tom Smith. Smith is one of the few people who can analyze the patterns contained within the database, and his research shows that bear attacks are anything but random events. Brush aside the blood and gore of these encounters and you can probe the age-old mystery that has chilled the marrow of many outdoorsmen: Why do bears attack?

ATTACK TRIGGERS

Three joggers decided to drive a short distance outside Anchorage and conduct a practice run down the McHugh Creek Trail in the Chugach Mountains. After climbing up a mountain, the joggers spread out and slogged down the trail, focused on making each step count. In their path was a dense alder patch with a brown bear on a moose kill. The surprised bear attacked and instantly killed the first jogger. The second ran into the fray and was also mortally wounded. The third, hearing the commotion and realizing it was a bear attack, retreated up the trail, climbed a small tree and stayed there until some hikers approached.

“Surprise is the biggest factor in triggering a bear attack,” says Smith. “When first startled, a brown bear is just trying to defend itself.”

Analyzing the story, Smith said the joggers made four major mistakes. “They were running in bear country. They were not close together. They carried no deterrents and made no noise. All the elements came together at the right time to create an attack. If they had been walking together, making noise and carrying pepper spray, the mauling would likely never have happened.”

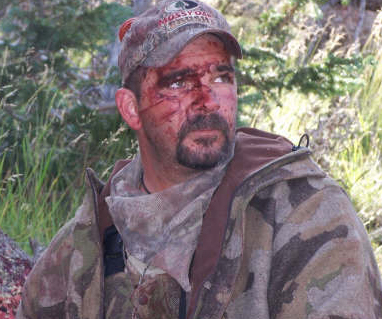

Hunters Most Susceptible

The database shows that of the different types of outdoorsmen who use the Alaska wilderness, hunters are the most susceptible to bear attack.

“Hunters typically aren’t making any noise, and they sleuth around while wearing camo,” Smith says. “Maybe they’re blowing a predator call-the database confirms bears sometimes approach people who use predator calls.” Many encounters take place at a downed animal, gut pile or bear-killed or scavenged carcass. Yet according to Smith, carcass defense is often misunderstood.

“Take your dog’s food while it is eating, and chances are he’ll bite you. You can do anything to the animal at any other time with no similarly aggressive response. Eliminate walking up on a bear and surprising it over a carcass, and you reduce the possibility of an attack by fifty percent.”

Browns Most Dangerous

Alaska has a population of about 7,500 polar bears, 35,000 brown bears and 110,000 black bears-yet brown bears account for more than 86 percent of all bear conflicts in the state. The average brown bear encounter is 13 times more dangerous than the average polar bear encounter and 22 times more dangerous than the average black bear encounter. Smith says this disparity is due to many factors. Black bears are relatively timid compared to browns and grizzlies, and polar bear habitat is restricted to remote regions with few people around. Humans interact more with brown bears on common-use land (such as berry patches, fishing streams and hunting areas) than with other species.

Wrong Place, Wrong Time

The matrix shows that bear attacks are seasonal in nature. Far more attacks occur in fall, during hunting season, than in spring. Summer berry season is another peak time for human-bear encounters. The time of day can also play a role in whether an attack happens. You stand a far greater chance of having an encounter by taking a nighttime walk adjacent to a salmon stream than you will by making noise alg that same stream during the daytime.

AVOIDING ATTACKS

Joe Want had journeyed far from camp and was heading back before nightfall. He could barely see the branches sticking out along the bear trail he was following. The trail was quiet as he hurried along, using what was left of the twilight, when he surprised a brown bear resting nearby. Startled by the quickly approaching form in the low light of dusk, the bear charged. Joe dropped down into a tussock, face first. The bear tore up his pack frame, which had slid over the back of his neck, and swatted at his arms and shoulders. Joe remained still as the bear vented its surprise and left. Injured, Joe made his way back to camp, thankful to be alive.

**Trekking in Bear Country **

Had Want been making noise or wearing the headlamp that was stashed away in his backpack, or had he slowed his pace a bit, chances are this incident could have been avoided.

Even during the day, don’t trek through bear country mindlessly while zoning out under your CD player’s headphones. Stay alert and walk ridges and trails that afford good views of the surrounding environment. Whenever possible, walk alpine ridges rather than brushy gullies and riverbanks. Use extra caution when walking through feeding areas, such as salmon streams and berry patches.

**Setting Up Camp **

How you set up your camp can make the difference between a sound night’s sleep and having your dreams interrupted by a bold bear.

“At least three-fourths or more of the bears that enter camps do so from 2 a.m. to 5 a.m., the time when people are most quiet and sound asleep,” he says. “I sleep well at night because I set up an electric fence around my camp.”

Electricity is an underrated bear deterrent, according to Smith. But you don’t have to set up a high-powered (and expensive) fence charger designed for cattle. Instead, visit a local home improvement store and buy a $39 fence charger that runs on two “D” batteries.

** Strength in Numbers **

Bears don’t like seeing more than one person. Smith says you can deter attacks by hunting or hiking close together. Moving over regular terrain you can walk 10 to 20 feet apart, but when you get into the thickets, it’s time to group up. That alone will work. Smith has no record of a bear that has charged and attacked two or more people standing their ground. “As soon as you split up, you stack the odds against you,” he said.

** FIGHTING BACK**

The biologists darted the grizzly from the helicopter, then landed. Approaching the bear to take blood samples, they sensed something wasn’t right. The bear moved, and moved again. Suddenly, from just 19 feet away, the bear charged the two researchers.

One biologist pulled a .44 and fired four shots at the bear, which quickly beelined for the brush. The pair ran for the safety of the helicopter cab. From the air, they noticed the bear still wandering around, so they darted it again. Upon examining the bear, they found that even at close range not a single bullet had hit the bear.

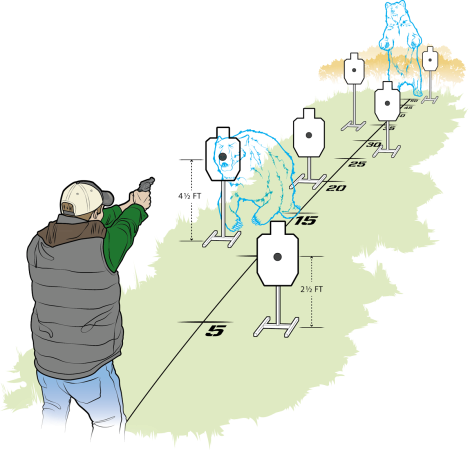

**Do Sprays and Guns Help? **

When it comes to arguing about the effectiveness of bear sprays vs. firearms as deterrents in bear attacks, both sides have valid points to make. The truth is that people don’t shoot particularly well under stressful situations like a bear attack, as illustrated by the above example. Sprays can also fail spectacularly as deterrents, especially when the canister is stashed in a backpack (as often happens) or if the wind is blowing the wrong way. But Smith says one thing is certain. Having a deterrent handy is much better than facing a menacing bear with nothing but your fists. For one, the spray or firearm gives you something to do other than run, which is the wrong response to an encounter.

“Just as backing away shows fear, standing confidently means something to a bear,” Smith says. “It’s very difficult to stand down a menacingly curious bear, but no matter what, it is imperative that people not back away.”

When All Else Fails

If you have sprayed or shot at a brown bear and it attacks, do not lie down. Instead, Smith says, turn your back to the bear and let it knock you down. Once you are knocked down by a brown bear, assume a defensive position by lying face down with your hands interlaced over your neck to protect it. Spread your legs to help keep you face down during the attack. Be still. Remember, the vast majority of brown bear attacks are defensive-the bear will nip, bite and swat for a bit and then move on. If the attack is prolonged-going on for minutes, perhaps-it is time to fight back.

Black bears are a different matter. “The majority of black bear attacks appear predatory,” Smith says. “You should always fight back.”

** LESSONS LEARNED**

Smith says that his study shows that a large percentage of bear-human conflicts are avoidable if a few simple rules are followed.

- Hike, hunt and fish in groups of two or more, keeping close in areas with limited visibility.

- Make noise when appropriate, such as when entering a thicket near a salmon stream.

- Always have a deterrent or two handy for dealing with a bear (e.g., pepper spray, flares and firearms). The database shows that in most conflicts bears were only defending themselves when surprised, and that their goal was to neutralize the threat and move on. Bears aren’t “out to get” anyone. Ultimately, the Bear Matrix shows that people and bears pretty much want the same thing: to be left alone to do their own thing, and not be surprised in the wild. ently means something to a bear,” Smith says. “It’s very difficult to stand down a menacingly curious bear, but no matter what, it is imperative that people not back away.”

When All Else Fails

If you have sprayed or shot at a brown bear and it attacks, do not lie down. Instead, Smith says, turn your back to the bear and let it knock you down. Once you are knocked down by a brown bear, assume a defensive position by lying face down with your hands interlaced over your neck to protect it. Spread your legs to help keep you face down during the attack. Be still. Remember, the vast majority of brown bear attacks are defensive-the bear will nip, bite and swat for a bit and then move on. If the attack is prolonged-going on for minutes, perhaps-it is time to fight back.

Black bears are a different matter. “The majority of black bear attacks appear predatory,” Smith says. “You should always fight back.”

** LESSONS LEARNED**

Smith says that his study shows that a large percentage of bear-human conflicts are avoidable if a few simple rules are followed.

- Hike, hunt and fish in groups of two or more, keeping close in areas with limited visibility.

- Make noise when appropriate, such as when entering a thicket near a salmon stream.

- Always have a deterrent or two handy for dealing with a bear (e.g., pepper spray, flares and firearms). The database shows that in most conflicts bears were only defending themselves when surprised, and that their goal was to neutralize the threat and move on. Bears aren’t “out to get” anyone. Ultimately, the Bear Matrix shows that people and bears pretty much want the same thing: to be left alone to do their own thing, and not be surprised in the wild.