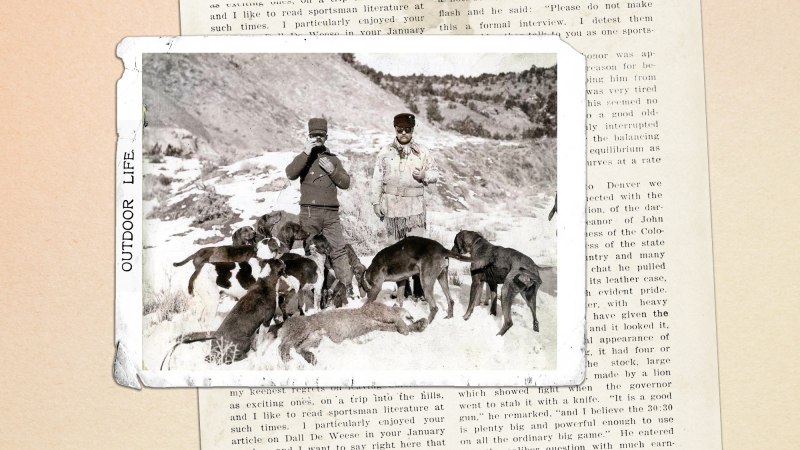

There was nothing easy about frontier life. If you lived into your 40s, you were a novelty. Those who survived were of hearty stock, and their tales of survival still live today. We sifted through the stories and found some of the hardiest frontier folk to live through it all. Keep in mind, for the most part, these are indeed stories and tough to verify. So take them with a grain of salt. If just half of their trials are true, then “tough” doesn’t begin to describe them.

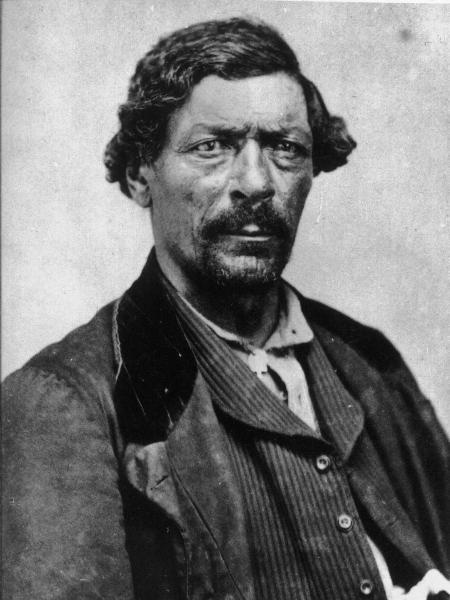

James Beckwourth (1798-1866)

Compared to life as a slave, life on the frontier must have seemed like been Club Med. This might help explain why this one former slave went on to become one of the most famous mountain men of the West. Born into slavery in Frederick County, Virginia, Jim Beckwourth’s mother was a slave and his father was an Englishman. Roughly 20 years later, Beckwourth received his freedom and hooked up with General William Ashely’s outfit, the Rocky Mountain Fur Company. Called “Ashley’s Hundred,” this group of trappers working the Rocky Mountain West was a who’s who of mountain men. Men such as Jim Bridger, Hugh Glass and Jedediah Smith were among the 100, and Beckwourth no doubt learned how to survive on the frontier with the best. Beckwourth’s time on the frontier is captured in the book The Life and Adventures of James P. Beckwourth, Mountaineer, Scout, and Pioneer, and Chief of the Crow Nation of Indians. While some of the numbers are embellished in the book, the events recounted by Beckwourth likely happened. And they may even have happened to him.

Hugh Glass (1783-1833)

As Hugh Glass crawled, dragged and limped some 200 miles from Fort Kiowa after being mauled by a grizzly and left for dead by his “companions,” I have to wonder if his fuel to live came from revenge or the off-chance that he would help Leonardo DiCaprio win his first Oscar. Unless you’ve been living a mountain man’s existence these past couple years, you’ve likely heard of Hugh Glass and his famous crawl. Before his bruin encounter, Glass was forced to be a pirate alongside Jean Lafitte. He and a companion escaped near Galveston two years later. After their escape, they were captured by the Pawnee in Kansas. Glass watched as the Pawnee impaled and burned his friend alive, and Glass gave the gift of cinnabar to the Chief. This saved his life. He went on to join the Rocky Mountain Fur Company where he met a young Jim Bridger and John Fitzgerald—the two men who would leave him for dead. Glass eventually reunited with both men, but killed neither.

John Wesley Powell (1834-1902)

Mountain Man? Maybe. Canyon Man? Absolutely. After losing his right arm at the Battle of Shiloh in the Civil War, Major Powell, at 35, strapped a wooden chair to a wooden boat, enlisted nine men and floated his way down the Grand Canyon, making the first ever-run through the canyon by a bunch of white guys and possibly by anyone. The journey started in May of 1869 on the shores of Wyoming’s Green River. Before hitting the mighty Colorado, the crew only lost one man who walked away, but most of their supplies had been lost to the rapids. Over the next two months, the crew had to portage what they could and run what they couldn’t. At Separation Canyon, three men had decided they would rather hike out and brave the desert, than almost surely die from starvation or drowning in the canyon. Two days later, the remaining crew floated out of the canyon. Those who hiked out were killed by Shivwit Indians. Powell went on to head the U.S. Geological Society, and he is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Marie Dorion (1786-1850)

Hardship is one thing. But throw a couple of kids under the age of 10 into the mix, and you get one hell of a miserable time. But none of that stopped Marie Dorion. A member of the Iowa tribe, Dorion married Pierre Dorion as a teenager, and she accompanied him on a trip west, after he was hired by John Jacob Astor’s fur-trading company to find easier routes. In tow were her five-year-old, two-year-old and one on the way. After setting out from their Midwest home, Marie gave birth to her third child nine months later in Oregon, but lost it eight days later. In January 1814, she took the kids and a horse in search of her husband’s camp somewhere in Idaho. Upon arriving, she found he had been killed and only one man was alive. She loaded him on the horse, but he died soon thereafter. Then, upon arriving back at her home camp, she found everyone there had been slaughtered as well. She loaded up her boys and some food and started heading west out of hostile territory. For three months they crossed the snows of the Blue Mountains and eventually had to eat the horse. After surviving the winter in the mountains and walking some 250 miles, she and her boys came to the Columbia River where the Walla Walla tribe helped her recover. She went on to remarry and have more children, the ancestors of whom settled the Willamette Valley.

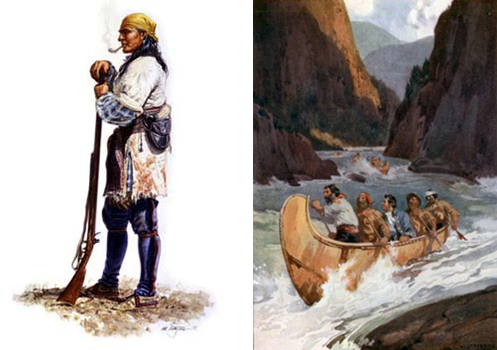

John Colter (1774-1813)

Enlisting in the Corps of Discovery in his early 30s, John Colter had a seriously wild bachelor life. On his way back east after hitting the Oregon Coast with Lewis & Clark, Colter got permission to leave the expedition and join two trappers for the lucrative beaver trade. Colter helped build a fort at the mouth of the Bighorn River in present-day Montana, and he made the first reports of hell on earth (geysers and fumaroles) in and around Yellowstone. His biggest claim to fame, though, is known as Colter’s Run. As a mountain man, one is predisposed to be fit, lest one dies. So when he was busted trapping by some Blackfeet Indians near the three forks of the Madison, Jefferson and Gallatin Rivers, which form the Missouri in Montana, he got to take the ultimate fitness test. He was stripped down and told to run, which he did. Warriors gave chase and he managed to escape by out-running all but one (he killed that warrior). He then jumped into one of the rivers and clung to a log jam with only his nose breeching the surface. His chasers gave up and he walked 200 miles east back to the trading fort he helped build. After moving back east to Missouri and settling down in to family life, he died of jaundice when he was around 40.

Kit Carson (1809-1868)

When you’re number nine of 14 kids, you learn fast how to look out for yourself. And that’s just what Carson did. With no formal schooling, Carson never learned to read, opting to help on the family farm after his dad died when he was nine. At 15, he’d had enough. He joined a wagon train out of Missouri bound for Santa Fe. At 19, he started trapping in California and throughout the West. At first, Carson seemed to have real disdain for Indians and loved a good fight, of which he had many. As time wore on, he married into local tribes (yes, he married more than once) and this softened him a little, but not much. While escorting his daughter back east, he met John C Fremont on a Missouri River steamboat. Fremont then enlisted Carson’s services to help him explore and map the central Rockies and the Great Basin. Fremont’s intention also was to market the West for would-be setters. He used Carson’s persona and tales of frontier adventure in his articles and reports, which promoted Carson to legendary status.

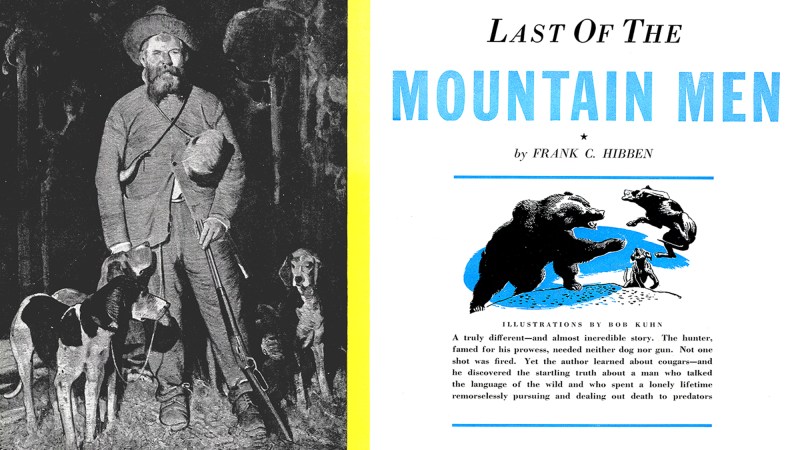

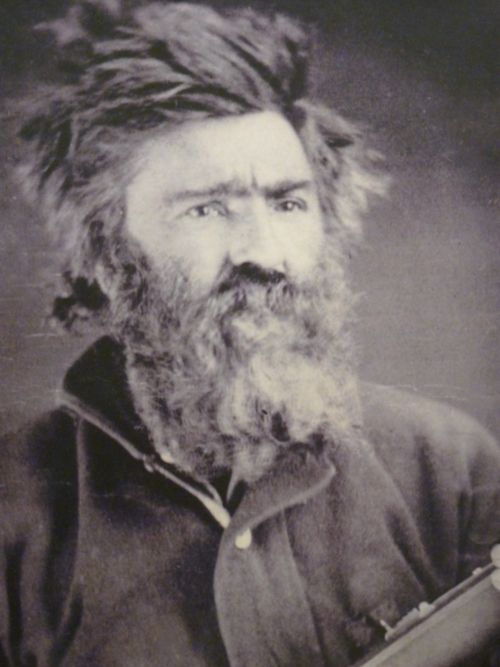

Jeremiah “Liver-Eating” Johnston (1824-1900)

Leo DiCapiro is to Hugh Glass as Robert Redford is to Jeremiah Johnson. As a boy, I watched the 1972 classic, “Jeremiah Johnson” until the tape eventually got stuck in the VCR. The movie is very loosely based on the life of John Garrison, whose life is an even greater bundle of lore, fantasy and downright fairytale. Regardless, it’s fun reading about the man real or imagined. We do know that he was born in New Jersey to a surly, alcoholic father who worked his six children to the bone. To escape this life, he works on a schooner hunting whales for more than a decade. After enlisting in the Navy, he knocked the snot out of an officer and fled west once he got his shore leave back. Since he deserted, he changed his name to Johnston. And that’s when the tales emerge. My favorite is how he vowed vengeance upon the entire Crow nation for killing his Flathead wife and unborn child. He went on to kill dozens of Crow warriors. When the Blackfeet captured him for the Crow bounty, he chewed through his rawhide handcuffs, beat up a guard, cut off the guard’s leg and used it as trail mix on his long road to vengeance. He died in 1900 at the National Soldier’s Home in Santa Monica, California.

George Droulliard (1775-1809)

If there ever was a “fixer” in history—like Harvey Keitel’s character in Pulp Fiction—then Droulliard was it. Hired on by Lewis & Clark in 1803, he recruited crew members, interpreted, scouted, hunted and tracked everything from elk to deserters. Droulliard was chosen to deliver the first letters written by Lewis & Clark to President Jefferson. The son of a French Canadian father and Shawnee mother, Droulliard signed on to Manuel Lisa’s fur trading party. This was the same outfit John Colter joined. While Colter left the Three Forks area of present-day Montana after too many run-ins with the Blackfeet, the lure of beaver pelts was too much for Droulliard. Near the headwaters of the Missouri where Colter made his famous run, he was killed and mutilated by members of the Blackfeet and Gros Ventre.

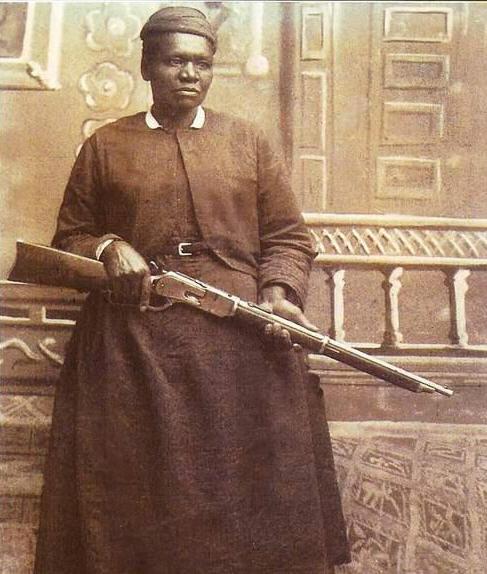

Stagecoach Mary Fields (1832-1914)

If there ever was a tougher woman than Mary Fields to walk Montana’s frontier, I would like to know. A former Tennessee slave who found her freedom after the Civil War, Fields was a six-foot solid mass of pure force. She got her name because she would always deliver (on time) the mail in and around the town of Cascade, regardless the weather or road conditions. She loved to drink at the bar alongside the men-folk and if one were to ever get wise, she’d just as soon break his nose than ask for an apology. When a young Gary Cooper met Mary, he later recalled the meeting in a 1959 article for Ebony, “Mary lived to become one of the freest souls to ever draw a breath or a .38…”

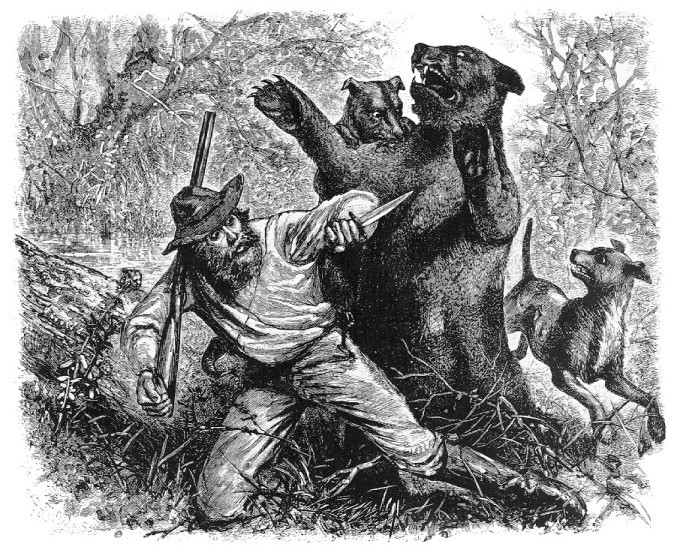

Jedediah Smith (1799-1831)

It seems as though the West had a grizzly bear behind every lodgepole pine. One nearly killed Hugh Glass, and another nearly ate Smith alive. Smith and around a dozen men were meandering down the south fork of the Cheyenne River when a large grizzly burst from the shadows. It broke ribs, slashed Smith’s belly and chest eventually putting all of Smith’s head in his mouth. When the smoke cleared and the bear retreated thanks to Smith’s men, things looked bleak. With scalp and one ear nearly ripped clean off, Smith had his men patch him up as best they could. After ten days and many stiches later, Smith decided it was time to break camp and move on. He and his men continued on through the Mojave Desert and California. For seven more years, Smith continued to explore and keep his hair long to cover his mangled memento thanks to that bear. In the end, a group of Comanches likely killed him near present-day Kansas.