You have one fall turkey tag in your possession.

You’ve roosted an early-hatch, good-sized family flock of several brood hens and birds of the year. The fall jakes are the size of the mama hens, and though they can barely muster a gobble at the end of their yelps, you’d like to take one of them home in your turkey vest.

The next morning, setting up where you’ve seen the turkeys sometimes feed on pre-frost, field-edge grasshoppers and the like, you hear a loud, far-off gobble on the next hillside, echoing down the hollow in the other direction. That bird is new to you, and seems to be alone. It has got to be a longbeard, you reason.

You love hunting longbeards as much as big bucks. What do you do?

The big flock starts clucking and yelping on the roost, not far from the field edge where you’re sitting at the base of an oak tree. It sounds like a barnyard. The far-off gobbler sounds off again, and another male turkey roosted with it does too. Suddenly it seems like spring again, not fall turkey season.

Do you get up and go to the loudmouthed autumn gobblers? Do you stay put and try to kill a legal either-sex bird from the family group?

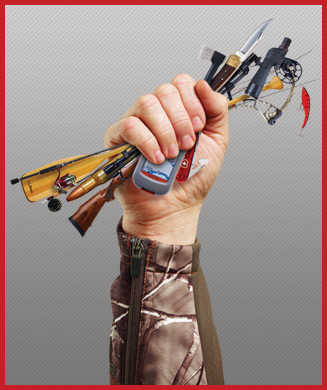

In spring, mature toms are inclined to seek out hens to breed them of course. Our calling tradition then focuses around making clucks and hen yelps to lure gobblers in. In fall, adult male turkeys (and sometimes “super jakes” not yet two years old) roam in gobbler gangs. Survival–primarily roosting and feeding–and pecking order rule their movements. To call a fall longbeard to the gun or bow you have to adapt your calling. Clucking, gobbler yelping and gobbling can do that. Sometimes.

So what do you do Strut Zoners? You make the call.

(NWTF media photo)