This story was originally published as “Those Korean Trout” in the September 1953 issue of Outdoor Life. You can read more about the author below.

The day was unbelievably hot, and the dust which the marching troops kicked up coated everything-even our throats. We men of the First Marine Division were moving back from the lines for a week of rest in X Corps Reserve, so we minded neither the heat nor the dust. Time and again my eye wandered to the cool, fresh waters of the mountain stream that cascaded along beside the twisted trail we were following. The entire Korean countryside was clad in the fresh green splendor of spring, a welcome relief from the bitter winter.

This was the first spring I could remember that did not involve plans for trout fishing. However, we were going into reserve, and that meant a week of nothing but rest, letter writing, and mail calls. We were only about three miles from the front and could still hear the thundering of the artillery. But that sparkling stream by the roadside made the war seem a million miles away.

Read Next: Hunting Ducks from a U.S. Naval Destroyer During the Korean War

It was a feeder that emptied into the Pukhan River. That same morning I’d seen Korean civilians dynamiting the river with hand grenades and scooping dead trout from its surface—some of them looking as long as my arm. It occurred to me that if there were trout in the Pukhan, shouldn’t there be some in its feeder streams?

After that it was like old times; I was planning a fishing trip. My plans hinged upon where we would camp. Luck was with me; about 1700 hours (5 p.m. civilian time) we halted beside the stream. By the time my buddy and I had dug our foxholes and set up our shelter there wasn’t enough daylight left for fishing, but enough for me to rig up some tackle.

Our radio operator had broken an aerial, so I salvaged it and disjointed it. With makeshift guides it would serve as a passable substitute for a fly rod. It was considerably stiffer than most rods, but it would do. When a case of C-rations was broken open I retrieved the wire, borrowed pliers from a communications man, and started to fashion guides, which I wrapped to my “rod” with individual strands of communication wire.

The rubber-covered wire itself wasn’t unlike fly line except that it was heavier and, of course, had no taper. But it turned out to be too heavy to handle well, even on the stiff aerial rod. For leaders, I used some separated strands. It was pretty difficult to form loops in them but I finally managed. The only thing I could find remotely resembling a reel was an empty spool from my sewing kit; it would serve to hold line but would be useless in playing a fish.

My consternation was great when considerable digging failed to produce any worms. I had absolutely nothing I could use for a lure. But then a man came in with one of the ringneck Chinese pheasants you see all over Korea.

I begged some feathers from him, fashioned a crude hook out of C-ration wire, used some thread from my kit, and tied the most fantastic and awkward looking fly ever seen by a fish. I’d never tied a fly before, so this huge, ungainly one was like no insect that ever existed, but it was gaudy and colorful.

Now all I had to do was wait until morning. Doubts immediately filled my mind. I wasn’t at all sure there were trout in the stream, and if there were I certainly wasn’t very well equipped to take them. But at least I’d be alone on a stream again and get the old thrill of anticipation of what might lie around the bend. I’d know once more that feeling of inner peace and contentment that comes to a fisherman on a good stretch of water. My battle-jangled nerves could use a tonic like that.

There was no reveille next morning in the rest reserve but I was up in time to witness a beautiful Korean sunrise. The birds were singing and the entire countryside was bathed in golden sunlight; my eyes, accustomed to nothing but the dirt and blood and smoke of battle for more than two months, couldn’t get enough of that morning splendor.

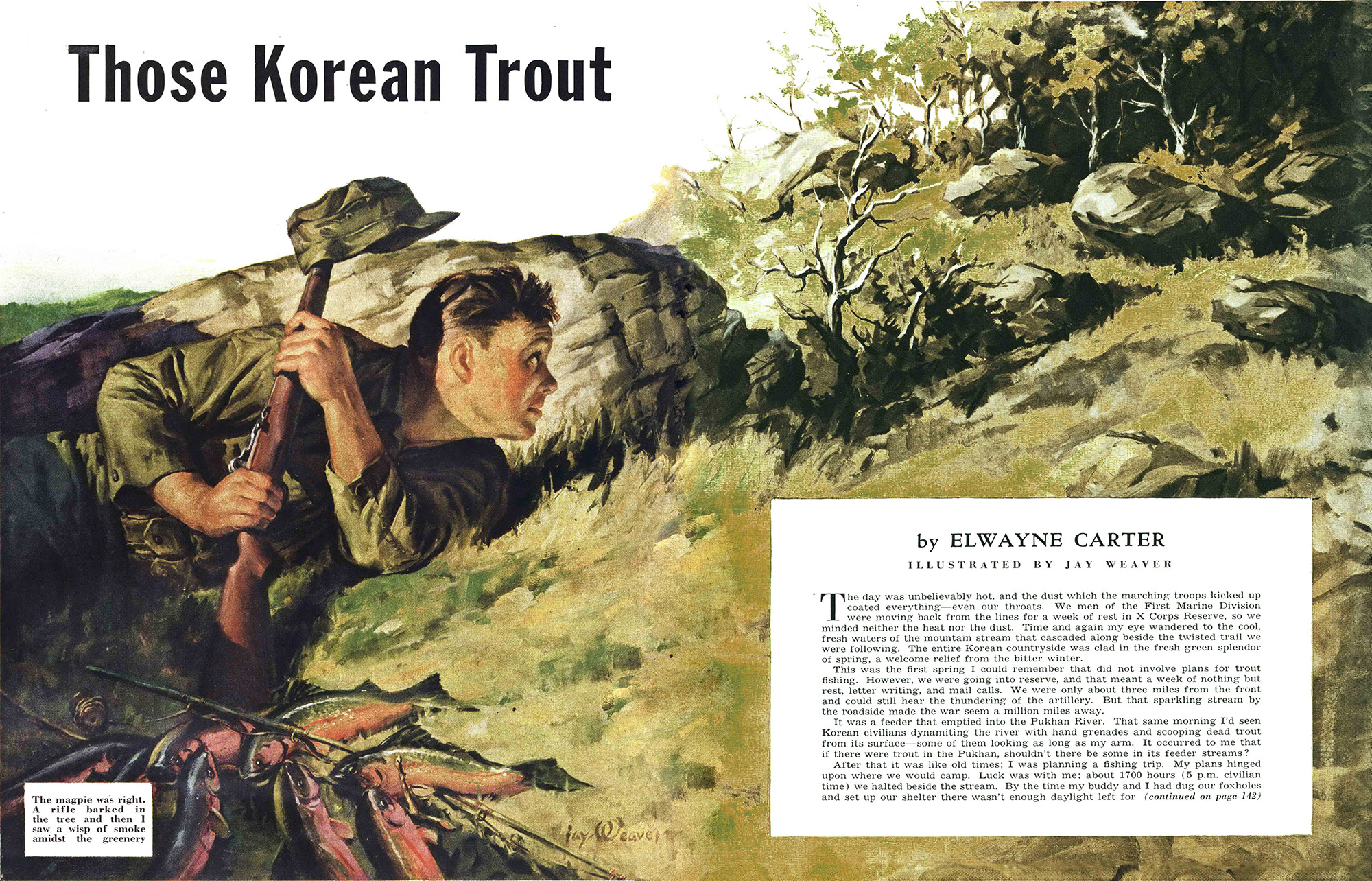

My fishing gear might be ridiculous but I felt the same keen sense of expectancy that pervades the angler in the States on opening day. Here I was on virgin water. If there were fish in that water they’d be both native and na’ive, for the Koreans fish only with traps or dynamite. The water was deep and clear but the stream was so narrow I could jump across it almost anyplace. I hung my M-1 rifle across my shoulders, picked up my makeshift tackle and my empty packsack, and started upstream. About a mile from camp I cast into a deep, quiet pool at the foot of a long, turbulent run.

At least I tried to cast; the heavy “line,” struck the water well ahead of the fly, causing a tremendous splash. I could see the flash of countless fish heading for the undercut banks. I had ruined this pool, at least for several hours. On the other hand, I now knew there were fish in the stream.

I ruined several other likely spots, too, before I jumped across stream and got the stiff breeze at my back. It was obvious I’d never be able to manage a good cast with the heavy wire. Below me the stream made an abrupt turn, its waters surging into a whirlpool at the opposite bank. I stood about 15 feet from the near bank and let the wind carry my fly over the stream and dap it gently on the surface. There was a miniature explosion in the water and the fly disappeared.

I didn’t even have to set the hook; the tight line and vicious strike had taken care of that. I’m sure that anglers will understand the elation that was mine; words fail me when I try to express it. Here I was, fast to a fighting trout again after two years away from all fishing and four months of the dreary, slugging work of battle.

Unfortunately the weight of my tackle made the struggle brief, and I soon lifted 11 inches of very tired trout up onto the bank. He was more welcome to me than larger fish had ever been, and I stood there for some time admiring his beauty. He didn’t look like any trout I used to catch back home in Colorado. He had the same shape as they, but his belly was a brilliant red-orange. His dorsal fin was heavily spotted while the others were plain. A bright-red lateral stripe ran from head to tail, and his back was olive colored.

All the fish I caught after that were of the same type, and I caught plenty. Every time I managed to get my fly quietly onto the surface, in any pool or pocket, a fish would hit it immediately.

Like all anglers, I had long dreamed of fishing virgin waters that teemed with fighting trout, and here it was. Because of my awkward tackle I missed countless strikes that I ordinarily would have hooked, but just the same caught about 100 fish that day.

If that sounds hoggish, remember this: the men in my platoon had been eating nothing but C-rations for months, and you can imagine what they’d do to crisp fried trout. I felt justified in taking as many as I could.

I FOLLOWED the stream through rugged hills and green valleys, taking fish from every likely pocket. When the sun was straight overhead I put down my tackle, rifle, and sack ( now bulging with fish), and ate a lunch of C-rations.

For the first time since I’d landed on the forbidding peninsula four months earlier

I felt perfectly at ease, remote from war and killing. It was like living in a dream, and the C-rations were my only contact with reality. I don’t know exactly how long I lay there reminiscing about other fishing trips but it must have been a couple of hours. Finally I got started again, since I wanted every man in my platoon to have his fill of trout.

The sack held about 50 fish, and I soon had it filled. When that was filled I used a stringer made of communications wire. The trout made quite a load, but my back was accustomed to take it. I fished along, quite forgetful of the war and quite ignorant of the fact that I was in an area which had been by-passed by our troops and not entirely cleared of the enemy.

I had reached a point in the stream where the water slowed down and deepened into long, glassy stretches with frequent bends and undercut banks. A big trout came up to my gaudy fly but I missed the strike. I put the lure down again, hoping he’d have another try at it.

Just then I saw a little puff of dust rise at my feet. My battle reflexes sent me flat on the ground—I was falling when I heard the crack of the rifle.

I landed behind a long rock about a foot high. As long as I lay motionless nothing happened but every time I tried to move, the dust would puff up in front of me and I’d hear the rifle bark.

There’s nothing like being shot at to convince a person that a bullet really travels faster than sound.

I wasn’t able to raise my body enough to unsling my M-1, so I unfastened the sling claws, removed the sling completely, and finally got the rifle around into my hands. I knew that somewhere beyond the rock a sniper was concealed.

But where?

I finally squirmed into a position from which I could peer around the edge of the rock without drawing fire, and I carefully scanned every inch of possible cover.

But all to no avail; that sniper was expertly camouflaged. I don’t know how long I lay there straining my eyes but it seemed like an eternity. I could—and did—deliberately draw shots in an effort to locate his firing point but there was just too much cover to watch, and I couldn’t concentrate on any part of it.

The sun was approaching the horizon, and I was beginning to wonder if I’d have to spend the night where I was, when a magpie approached a tree as if to light. But it turned and flew away, squawking raucously. That was my clue. Every other point of cover but that tree was now eliminated. But even so I couldn’t find the sniper in it. This called for strategy.

I removed my cap, placed it on the muzzle of my rifle, and slowly raised it above the rock. I knew that the enemy used an inferior grade of smokeless powder, and my ruse worked perfectly.

I heard the shot, then saw a wisp of smoke in the greenery. I carefully got my sights on the spot and squeezed off a round. I heard the sickening thwack of a bullet hitting flesh and watched the sniper topple from his hiding place amidst a shower of branches, twigs, and leaves.

He was dead when I got to him. Right then and there I took a solemn oath never to shoot another magpie.

Since it was now too late to do any more fishing I returned to camp with my catch. The trout ranged from seven to 15 inches, and I got lots of willing help in cleaning them. Then we built a fire, stuck the trout on sharpened sticks, and roasted them like hot dogs. I’ve never tasted anything better in my life.

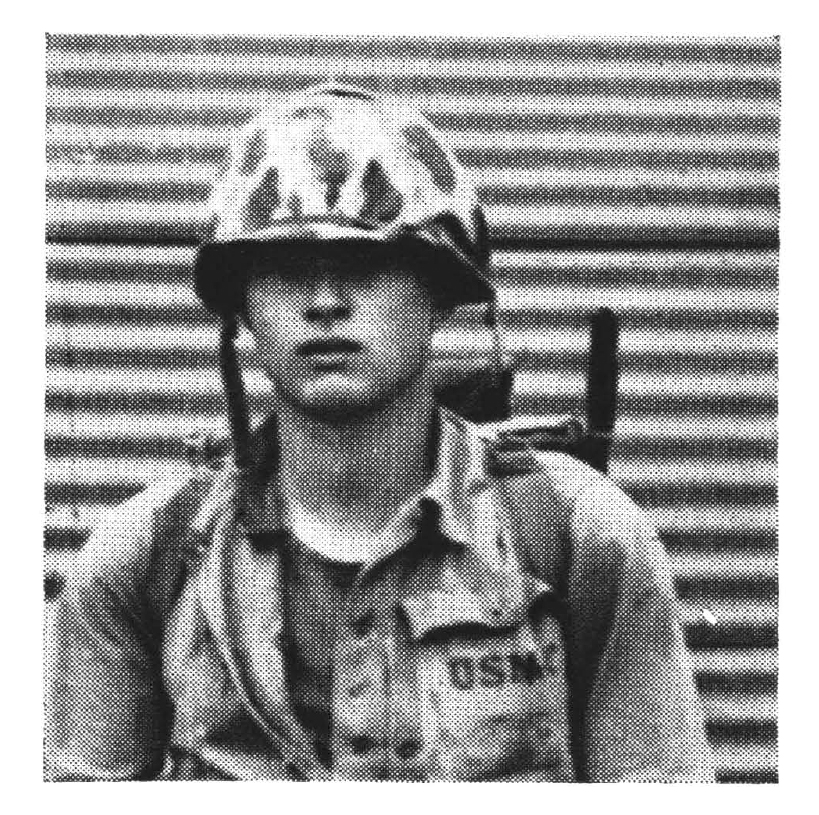

This is Elwayne Carter, who tells you how he caught “Those Korean Trout” and nearly lost his life doing it. A Marine Corps veteran, he has lived since boyhood with an uncle and aunt in Colorado. Both ardent outdoors people, they taught him to love fishing and hunting.

“Every Sunday during Colorado’s long fishing season,” he writes, “we were on the North Fork of the South Platte and other streams in the area.” The trout were usually willing and able, but never did Carter run into such astonishing fishing as he found within sound of battle.

Read Next: Want to Honor Our Military Veterans? Take Them Hunting

He served with the First Marine Division in Korea from December, 1950, to June, 1951, and was discharged that summer. Now he’s majoring in journalism at the University

of Colorado. Incidentally, he wrote this story as part of his class work; his professor urged Carter to send it to OUTDOOR LIFE. The editors agree he’s done a good job.