Josh Dahlke figured he’d never get a shot at a bighorn sheep. The Minnesota hunter was in his late 30s and had just started applying for points. In many states, his odds felt like winning the Powerball lottery.

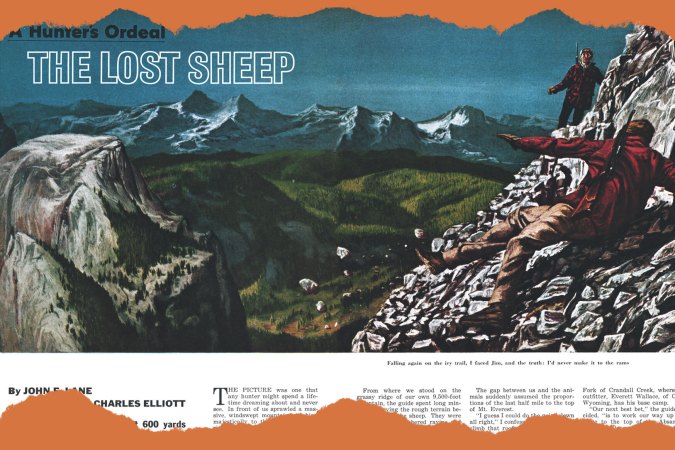

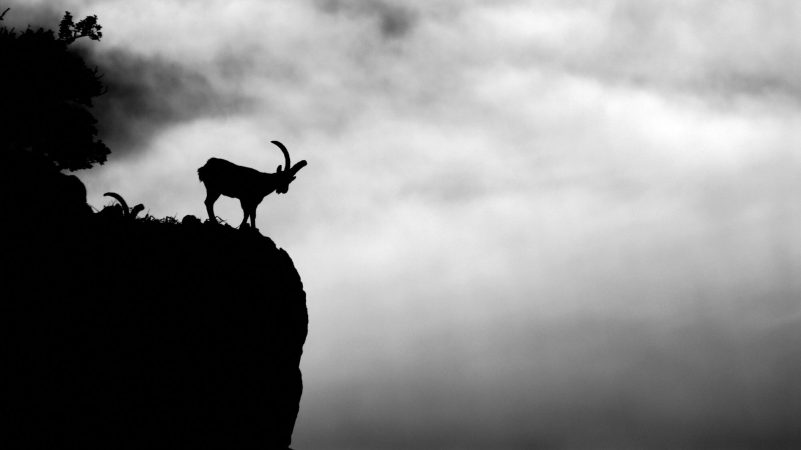

But a few years ago he found himself in Colorado on a talus slope above 12,000 feet with his rifle aimed at the gray, wooly vitals of a Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep.

He pulled the trigger, the sheep dropped, and the work to pack out some of the most delicious meat he’d ever eaten began.

Dahlke’s sheep hunt wasn’t a result of beating the odds. He hadn’t mysteriously earned 20 more preference points or won the lottery. Dahlke had just switched his sights from a bighorn sheep ram with a full curl to a ewe. He made a simple economics decision and applied for a tag with decent supply and exponentially less demand.

And after a 24-hour pack out with two buddies that included an emergency overnight stop with no water or food (besides sheep meat), Dahlke can attest that the only difference between a Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep ewe hunt and a ram hunt is the mount on his wall.

As bighorn sheep ram tags become increasingly hard to draw — a result of more applicants, diminishing nonresident allocations, and struggling sheep populations — some hunters are changing their goals. At the same time, some wildlife managers hope more hunters will shift their sheep hunting aspirations from big old rams to the old ewes that live in the same spectacular places and offer the same once-in-a-lifetime hunts.

“I’ve never been much of a trophy hunter from the perspective of horns and antlers,” says Dahlke, who has stalked big game across the globe. “I’m a trophy hunter from the perspective of the other half of it, the conservation side. And so to me, it didn’t matter at all that it was a ewe.”

Chasing Ewes

Ewe hunting isn’t new. It’s also not what most bighorn sheep hunters like to talk about.

“There are a lot of guys who call themselves sheep hunters and might never sheep hunt because they can’t get a tag. There are folks who call themselves sheep hunters and only scout them or go on someone else’s hunt,” Dahlke says. “People are very passionate about it, but it seems like sheep hunting is synonymous with shooting a ram.”

Yet everything about the experience – from scouting to camping to trudging up steep mountain faces – feels the same as a ram hunt would. And Dahlke can’t stop talking about the quality of the ewe meat.

Plus there are those odds: Only 70 nonresidents applied for Wyoming’s three ewe tags in one area last year, and 65 for another area’s two licenses. Comparatively, more than 1,700 nonresidents applied for the state’s lone lottery ram license. Ewe tags also may not use preference points depending on the state. They don’t in Wyoming, and successful applicants can apply again after five years.

And depending on the state, hunting licenses for ewes may run you far less than ram licenses. A ewe/lamb tag in Wyoming costs $240 compared to $3,002 for a ram tag.

Then there’s the fact that many wildlife managers would really like hunters to apply for ewe tags and, if successful, shoot one. Herd numbers are expanding in some areas, which increases the chances that a satellite ram looking for love will encounter a domestic sheep or sick bighorn from another herd and bring illness back home. Too many wild sheep on a landscape also puts pressure on food resources, leading to skinnier animals that are less hardy.

For years, Wyoming biologists have tracked a herd in the Jackson area and watched it grow then shrink, grow then shrink. They realized that if population numbers climbed much above 450, sheep had less fat and as a result, were more susceptible to disease, predation, and hard winters. Herd numbers would crash, then slowly climb again.

Instead of waiting for the herd to lose half its members to a bad winter or pneumonia outbreak, biologists proposed hunting ewes to keep the population around 400, better matching what the habitat could support. Shoot some ewes, the biologists said, to keep even more from dying.

The same concept is being applied to other herds in Wyoming, Colorado, and other western states both to keep herds stable and to prevent those wandering wild sheep from bringing back disease.

“It’s not only an opportunity for hunters,” says Kevin Hurley, vice president of conservation for the Wild Sheep Foundation, “but a management tool.”

A (Nearly) Impossible Draw

Depending on the state, nonresidents may only receive a handful (or fewer) bighorn sheep ram tags each year. Take Wyoming for example. The Cowboy State legislature recently changed nonresident allocation from 25 percent to 10 percent, dropping the number of nonresident tags by half. In 2023, nonresidents vied for 22 tags with only one of those up for grabs in a random draw. (The others are allocated in a point system). Wyoming Game and Fish biologist Daryl Lutz knows residents who may well wait a lifetime to draw a bighorn sheep. Most nonresidents will never draw.

Other states may offer slightly more tags in random draws, but run the numbers and your chances still aren’t good. Don’t even think about Canada unless you’re willing to shell out six figures. The only way non-Canadian citizens can hunt a wild sheep is with a registered outfitter, which may well cost over $100,000.

Read Next: I Finally Drew a Bighorn Sheep Tag. I Was Too Out of Shape to Punch It

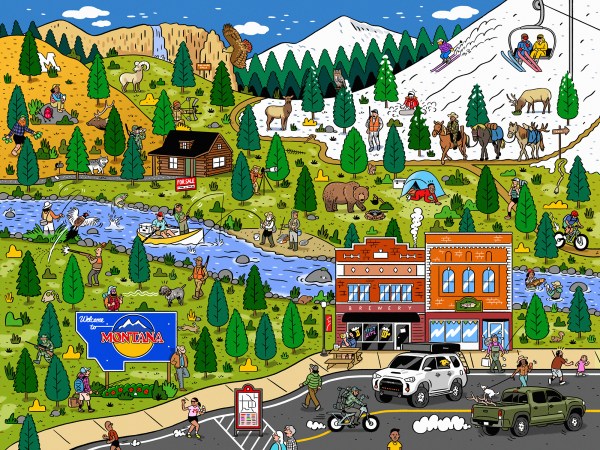

Montana offers a handful of over-the-counter general area wild sheep hunts to residents and nonresidents. But there’s a catch. Hunters can only kill two rams with three-quarter curl or bigger, and the hunt ends within 48 hours after the quota is met.

It’s this reality Will Downard faced when he considered hunting bighorn sheep. The central Iowa hunter grew up chasing whitetail deer close to home and elk and mule deer in the West. A bighorn sheep seemed like an impossibility. Until it wasn’t.

He sat down years ago at a trade show dinner with a guy who had ideas. The man told Downard about the Montana hunt and asked him if he’d consider hunting ewes.

“He told me there were ewe hunts where you could draw one easily if you knew where to look,” Downard says. “He didn’t give me exact information, but he hinted around areas to start looking.”

Downard applied for a ewe hunt in Colorado in 2017 and drew the first time.

“If anything, it was a huge excuse to go and explore the mountain tops,” he says. “I fell in love with it.”

Getting Over the Full Curl (or Not)

The first hunt someone applies for in a new state is not usually a bighorn sheep. But Kylie Schumacher thought she’d play her odds after moving to Montana, and she applied for everything.

To her surprise, she drew a ewe tag. Then she researched the hunt with help from locals and YouTube, borrowed a canoe and dry bags, asked a friend to come with her and headed out. The two women would spend five days floating the Missouri River through the famous Breaks, a region prized for its sheep hunting.

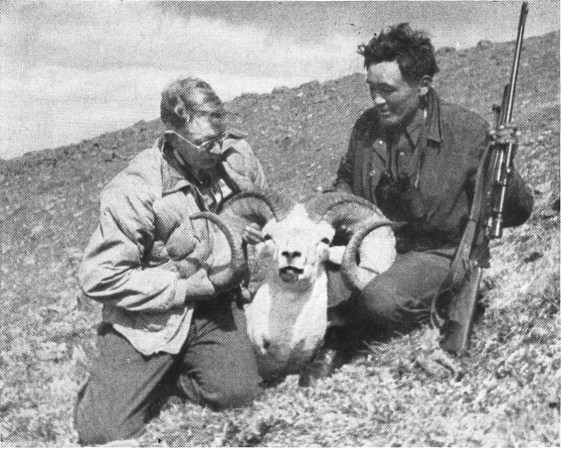

They found a herd on their first morning and then another on the second. After spending a day watching them, Schumacher shot and processed the sheep on a wedge of cliff rock just big enough to hold the two hunters and the ewe.

She doesn’t feel like she missed out by hunting a ewe and not a ram, but she’s still putting in for preference points for a ram tag.

“People come to hunting from different perspectives,” she says. “For people who grow up hunting and have met the objectives out there, something like a ram is the ultimate challenge.”

Kevin Monteith, a University of Wyoming professor who’s spent well over a decade studying bighorn sheep, understands the utility of hunting ewes. He’s also an avid big game hunter and taxidermist.

Monteith says he would harvest a bighorn ewe and fill his freezer with the meat, but that he would still really like to hunt a ram. He admits it might be his taxidermist side, and while he doesn’t want to be labeled what he calls “hornographic,” he says there’s something incredible about a full-curl ram.

“They are an amazing, regal, majestic creature of the mountains with their very heavy, spiraling horns, big faces, and burly bodies. Those are quintessential [qualities] of males and not females.”

Read Next: Can Sheep Hunting in the Yukon Survive Another Century?

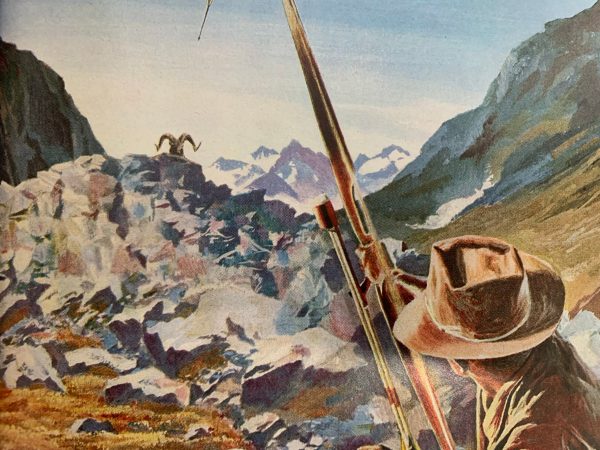

Downard has a tough time articulating how he feels about the full curl. He was so proud of the 11-year-old ewe he shot with a bow in Colorado that he had a full-body mount made. But ever since then, he’s been putting in for preference points anywhere he can buy them. He’s got seven now in Colorado, and he’s tried his hand twice during Montana’s general season. Both were 10-day hunts, and he never saw a legal ram.

At this point, Downard says, he just wants to be among the bighorn sheep in the rugged areas where they live. Even when he’s hunting in that Montana general area, he figures it’s less about his desire to shoot a full curl and more about what that kind of hunt represents.

“At least for me, the significance of a big set of ram horns is the same as a big elk or whitetail. It’s so much harder because there are so far fewer of them,” Downard says. “It’s more satisfying to have done the work and been able to pull off something that’s nearly impossible.”