As soon as I hung up from a long phone conversation I checked the trail cam notifications I’d gotten, expecting to see turkeys. But the first thumbnail to pop up was a cougar. The images had been captured just two minutes prior; it was April 25, 2:20 p.m.

Within five minutes I was dressed and on the road. The mountain lion was cruising an old logging road in the foothills of the Cascade Range, less than three miles from my home in Western Oregon.

I had been hunting mountain lions in this jungle-like habitat for three years. I’d yet to kill one. This was a prime opportunity. As I drove to the spot, I couldn’t stop thinking about the close calls I’d had with cougars in these hills.

Close Encounters

Photo by Scout Haugen

Seven months ago my wife and I had just sat down for dinner at her folks. Before cutting into grilled elk steaks, a Moultrie Mobile notification popped up on my phone. It was a photo of a cougar. A big one. “I have to go, I’ll come back and get you after dark,” I said as I kissed my wife goodbye. I’d been after this lion for three weeks. Everyone understood. It’s how I’ve operated for many years.

I had a change of clothes, my rifle, and predator calling gear at the ready, so within 45 minutes I was sitting precisely where the cat had popped up on camera. It felt like a done deal. I had three photos of the big tom walking a narrow game trail atop a timbered ridge. It was too thick to get ahead of him and I was running out of daylight so I set up a Foxpro electronic call 30 yards up the trail from where I’d last seen the cat, intent on calling it back down the trail.

I was hunting during late summer so I started with fawn distress calls, as cats had been hitting them hard. I increased the volume, eventually switching to rabbit and squirrel sounds, and still, nothing. Defeated, I hiked out of the hills in the dark, wondering what went wrong.

Back at the truck I checked the app. That’s when I saw two pictures of the cat circling back. From the time I’d left the in-laws to the time I got set up, the cougar had come back down the trail, entering the brush it had originally emerged from. I’d set up and called for over 30 minutes where the cat had just walked by. He had been directly behind me in a thick tangle of brush and green foliage the whole time. Who knows how close it was — just sitting there, watching.

Five months later I received another trail cam notification. I get them daily — hundreds of them. This time, four Columbia blacktail deer were walking by a camera. Six minutes later, the camera was triggered again. This time more than a dozen deer crowded the frame and they were nervous. Blacktails aren’t like mule deer, they don’t gather in winter herds.

The deer sprinted into the brush and a few minutes behind them came the massive cougar I’d been after for nearly two weeks. Minutes later, the cougar emerged and it was dragging a deer. Sleep didn’t come easy that night.

At daylight I went to where the cougar had dragged the deer out of the woods, hoping to find it on or near the kill. It had been headed for an old logging road that was so overgrown with brush it could only be navigated on foot. Struggling to locate any sign, I backtracked and found where the cat killed the deer. Finally, I located a spot where the cat’s right paw had slipped on moist, green moss. Two hours later I found a similar mark over a half-mile from the first. I’ve tracked a lot of animals — both predators and big game — around the globe, and this was one of the toughest trails I’d ever worked.

Three hours later the silver underside of a blackberry leaf caught my eye. It was 10 yards off the trail. The vine had been pulled tight. When deer and elk hang up on vines they rarely drag them; instead, they step out of them. This one had been dragged more than five feet, indicating something was hung up on it.

I continued burrowing through the briars. Brush was dense on both sides, offering only a few feet of visibility. I followed more overturned leaves and strung-out berry vines. There was no trail, just knee-deep blackberries. As I looked ahead, I could see the cover ahead hadn’t been disturbed.

Two more steps and there it was: a freshly buried deer carcass at the base of a tall Douglas fir. I uncovered it and found where the cat had ripped into the body cavity, drank the blood, devoured the lungs, liver, heart, and the cartilaginous tips of a few ribs. It had eaten nearly all of the head. None of the prime meat was touched. The cougar would be back.

Quickly I got to chopping with a machete to create a shooting lane. Then I crafted a crude ground blind 70 yards away, across a little swale. All I could see through the tunnel was the deer carcass. It was perfect.

I left for a couple hours to let things settle down. At 3:00 p.m. I tiptoed into the blind knowing that the later it got, the greater the chance of the cat’s return.

Securing the rifle in a vise grip tripod, I settled the reticle on the deer carcass and waited. I stared through the scope so when the cat showed up all I’d have to do was pull the trigger. An hour into it I lifted my head slightly to give my neck some relief. That’s when the cat appeared.

Its blocky head materialized from nowhere and it was staring right at me. How that cat had seen me through tight brush I’ll never know. Slowly I lowered my head, confident this was it. But when I looked through the scope the cat was gone. I didn’t move for another 20 minutes, until darkness brought a close to my hunt. I’d just blown the best opportunity I’d had at this cat.

Chasing the Big Cats of Oregon

Photo by Scott Haugen

In Oregon, cougars are classified as a big game animal. If you find a cougar kill you can uncover it to inspect it, but the carcass cannot be moved. Neither can it be chained to a tree or tampered with. Cougars can’t be hunted at night in Oregon and, of course, hunting them with hounds here is forbidden. The odds are ridiculously stacked in favor of the cat. Using cellular trail cameras is legal, at least, offering the best chance of success in this challenging habitat.

Given the increasing number of pets being snatched off back porches, livestock being killed, and human encounters with mountain lions, you’d think the rules would change. A conservative estimate puts the number of cougars now roaming Oregon at 7,000 — twice the number of just 40 years ago. The one benefit we have is that cougar season is open all year, or until unit quotas are filled.

The mountain lions I hunt live around people. These cats are tough to kill. They’re smart. And they pattern us. They know when you go to work, when the kids go to school, when you let the dogs, out and when you’re hunting them.

I’d tried calling that big tom multiple times, as well as other cats in recent years. I’ve called year-round, with decoys and without, with electronic calls, mouth calls and a combination of the two. I’ve called in tight quarters where a 10-yard shot was the only option I had. There’s no open terrain where I hunt: only a few narrow shooting lanes along brushy game trails, closed-down logging roads, and narrow ATV tracks. Most of the time, 30 yards would be considered a long shot.

Following my close-encounter over the blacktail cache, I caught four different cats on trail cameras in this area. I have 38 cameras set for cougars, more than half of which are cellular. A number of successful cat hunters near my home — folks who know way more about calling cougars than I do — advised me to run cellular cameras wherever I could, and the moment a cat appeared, to get after it. All reasoned that the habitat is so thick, if you’re not on them right away, you’ll not pull them out of the brush.

Dozens of times I caught cats moving at night. I would get set up in that very spot and be calling at daylight, but no lions had come to my calls — at least that I know of. I had over a half-dozen daytime sightings on trail cameras, but they were often when I was traveling. I was in Alaska when the big tom showed up on three cameras three days in a row, all during daylight.

My addiction to outsmarting these cats began to govern my life. I started traveling less, sticking closer to home, setting more trail cameras, jotting detailed notes to pattern cat movements throughout the year, and looking at trail cam notifications as soon as they popped up on my phone.

Finally, on April 25, the timing was just right.

Point Blank

Photo by Scott Haugen

A trail cam showed a cougar had arrived at the fork of two ATV trails.

I was in position less than 20 minutes from when the cat appeared on camera. It had been at the fork of two ATV trails, and I guessed it had stuck to the upper path where it was brushier, with more green grass on it than the lower track. I confirmed it had traveled this track, which joined another track just over a quarter mile away. This junction is where I set up. I knew I’d have a 50- to 60-yard shooting lane down one trail, so I’d brought a 28 Nosler.

I set a Foxpro X24 less than 30 yards from me, on the other side of the trail I thought the cat would travel. Should the cougar pop out where I hoped, I figured it would turn uphill, away from me and go to the call. If the cat had already passed by and was headed up the mountain, I figured I could call it back.

A lot of cottontails and gray squirrels had been popping up on trail cameras, along with gray fox, opossum, feral cats, and deer; cougars eat them all. So for three minutes I played jack rabbit distress sounds. I started quietly, figuring the cat was near. By the end of the sequence it was on full blast, penetrating the thick stand of 15-year-old Douglas firs covering the ridge.

After a break, I slipped an open-reed cow elk call into my mouth and hammered away with bird distress sounds. This has been my go-to sound for calling in bears and coyotes in thick cover. Twenty seconds into the sequence, it happened.

A gray fox came barreling down the trail I’d expected the cat to travel, turned hard to the right, and sprinted right at me. I’ve called in a lot of gray fox and immediately knew something wasn’t right.

I was already on the gun, which was steady on its tripod, and I put my eye to the scope to track the scurrying fox. That’s when the blocky head of a cougar appeared. I had both eyes open and could see the cat as it sprinted off the hill, out of a curtain of lush green. Its thick tail turned in a perfect circle then smoothly centered-up for balance. The head and tail were steady as the cat lunged, turned 90 degrees to get on the fox, then dug in.

The cougar was 23 yards from me when it first emerged. In a fraction of a second the cat was stretched out right behind the fox. Now both were running full speed directly at me.

I was sitting on the ground on the left side of the trail. The fox came down the same side. So did the cat. There was no time to think.

When the green dot of my sight dropped below the nose of the cougar, I squeezed the trigger. At 16 yards, a 175-grain AccuBond pounded the cat in the chest. Its head dropped and the downhill momentum sent its hind end over the top. The long, thick, dark tail extended into the sky and fell toward me. It looked like I could reach out and grab it.

Instantly, I cycled another round but the cat was on its feet and into thick cover before I could shoot again. He vanished only seven steps from where I sat. I stripped off my hood and facemask to listen. I heard nothing.

There had been no time to get nervous. No shaking.

I stared into the brush but two feet of visibility was all I had, too dense for a rifle. I backed out and walked to the truck grab my shotgun: a short-barreled 12 gauge, loaded with 00 buckshot, and topped with a Trijicon RMR.

On the way to the truck I texted my buddy Tyler Tiller, who has killed a number of cougars in our area. He was home and 10 minutes later met me at the truck to help track the cat.

For the first 15 yards there was no blood, hair, or a visible trail in the dense brush. It was hands and knees tracking and the going was slow due to massive tangles of thorny blackberries. Tiller would study the ground for blood while I watched for the cat, then we’d switch. We were ultra-focused. It was tedious work.

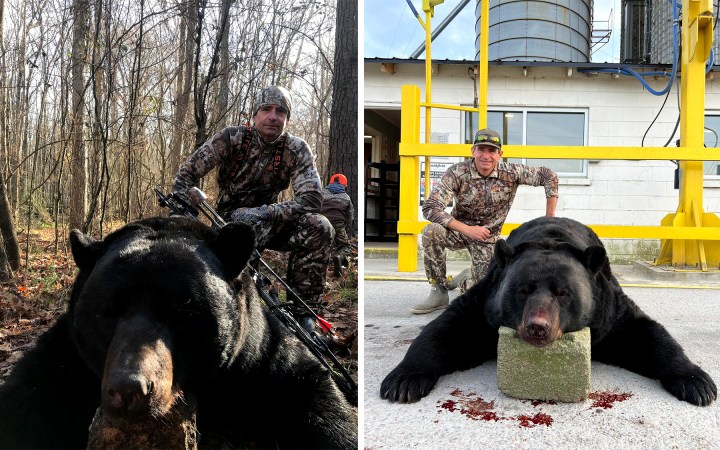

Ten more yards and the first blood appeared — lots of it. Fifteen minutes later and 20 yards further into the brush, I saw the cat piled-up in the bottom of the draw. It was just two steps from us, covered in briars.

Photo by Scott Haugen

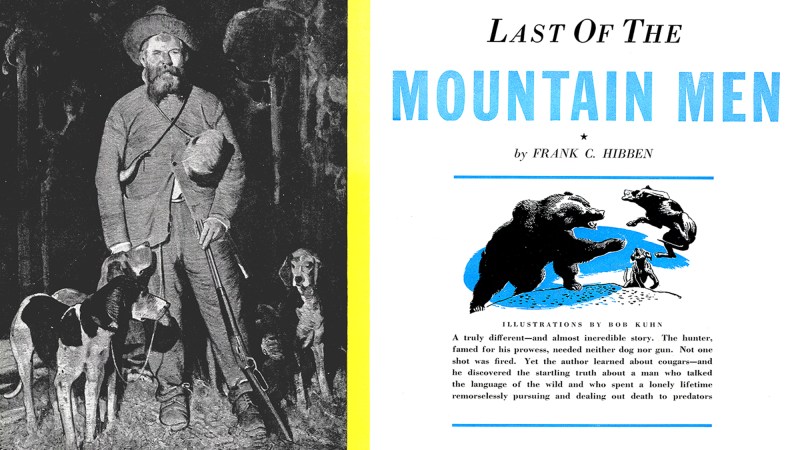

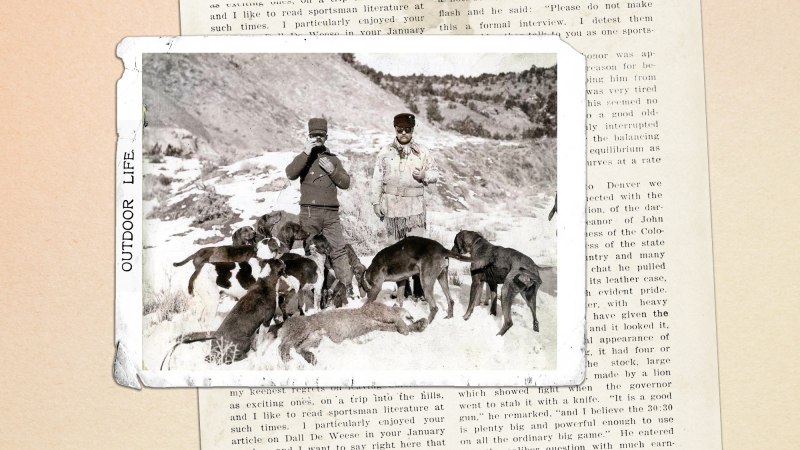

Read Next: Hunting Cougars with Ben Lilly, the Last of the Mountain Men

After three years of chasing cougars in these hills, my efforts were rewarded. Over the decades I’ve had the opportunity to hunt a number of dangerous game animals, including man-eating lions and crocodiles in Africa and a man-eating tiger in Sumatra. In 1990 I tracked down and killed a man-eating polar bear in Alaska’s high Arctic. Hunting big predators is a passion. Hunting them close to home is a treat.

“Now you can finally relax,” my wife said. But two weeks ago, another cat showed up in the same spot. And I have a second cougar tag in my pocket.

Scott Haugen is a full-time writer of 24 years. Follow his adventures on Instagram and Facebook and learn more at scotthaugen.com