This story first appeared in the July 1963 issue of Outdoor Life. While it is a classic example of a predator hunt in the 1920s and 30s, it also shows how predator management and hunting ethics have changed over the decades.

I DON’T KNOW how many times the cougar squalled before I finally woke up, but my awakening was certainly hastened by the realization that the cat was practically in bed with me. I sat up and stared vainly into the snow-filled ring of darkness surrounding my dying campfire. Somewhere, just outside that flitting black wall, a big cougar was watching me at a distance measured in feet. As a professional bounty hunter with nearly 40 cougar hides stretched out in the past few years, I felt no great fear. My only emotions were a mixed amazement and curiosity that one would come so close to my fire. My one cougar dog, Spot, had been sleeping under a shelter of boughs. Now she sat peering quizzically toward the sound. I threw back the big packsack which served as my only cover and reached for my boots. Again the heavy, guttural m-e-e-o-w rasped the night. I’ve heard cougars scream only twice, but I’ve heard them meow many times, often when they were hunting together.

I slipped on the boots and lit my small miners’ carbide lamp, my only source of light. The flickering glow was nearly useless in the snowstorm, but I walked toward the sound. I didn’t have far to go. Within 30 feet of the fire, I found big pug marks. They were practically sizzling when touched by the wet snow flakes. I walked back to the fire and threw on a big supply of wood. Then I strapped on my 7.63 mm Mauser pistol, a German weapon of World War I vintage with a combination holster and stock, and untied Spot. If this cougar was going to be brazen enough to wake me up, I was going after it. I estimated the time at about 11 p.m. If the cat pulled out and the snowstorm continued, I might not find its tracks by morning. I didn’t have any idea how I would handle the situation if and when I treed the cat. I only knew that I had climbed nearly 15 miles up the side of a ridge looking for cat tracks. I wasn’t going to pass up an opportunity like this, no matter what I might run up against.

It gave me a lot of satisfaction to hunt these cats. I had hunted and trapped coyotes professionally for years, but paid little attention to cougars. Then on December 17, 1924, James Fahlhaber, a 14-year-old orphan boy living with one of our neighbors, was killed by a cougar. At the time, I was living on my mother’s homestead in the Chiliwist Basin about four miles southwest of Malott, Washington. Jimmie, who lived with the Robert L. Nash family on an adjoining homestead, started on foot through a canyon to get a team of mules from a neighboring homesteader. He never arrived. I was one of the first to reach the grisly scene of his death. What I saw left me with an unquenched hatred for cougars and started me on a lifelong onslaught on all members of the breed.

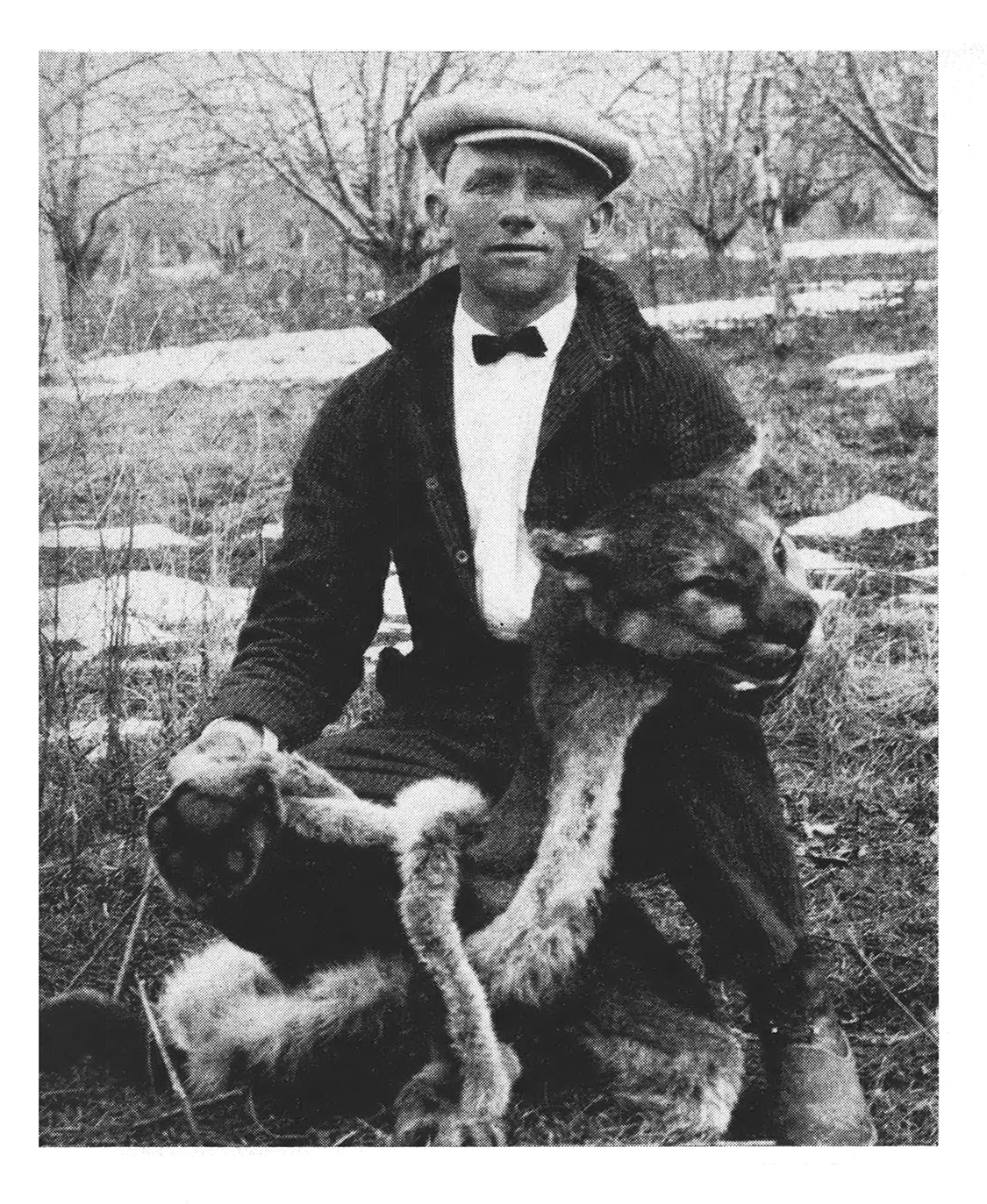

So far as I know, this was one of the few authenticated cases of a cougar making an unprovoked attack on a human. I might eventually have become reconciliated to this one case, but the hundreds of battered deer carcasses I have seen while following cougars have only heightened my hatred for them. I got Stub and Spot the same winter Jimmie was killed, and I declared war on cougars. I killed nearly 40 in the next three years, and earned such a reputation as a cat hunter that in 1929 I received the invitation to hunt them in Canada.

I had bedded down about 7 p.m. on a high ridge between Adams and Barriere Lakes in south-central British Columbia. It was December 22, 1929. Five days before I had entered Canada from the United States with Vernon Bawlf, a cousin who died in 1961. I had brought Stub and Spot and enough provisions to stay about two months. The British Columbia Game Commission had asked me to hunt the cougars that were causing serious depredations to deer and moose herds near Adams Lake. They offered me a bounty of $40 for each cat. (Editor’s note: This is the equivalent of about $670 in 2022.) As an added bonus, they gave me permission to shoot one deer for meat for every 10 cats I bagged.

We set up a base camp at Squim Bay, or Agate Bay as it is now called, about 10 miles above the lower end of Adams Lake. There was very little snow, and I had taken several cat tracks only to lose them on open ground. I decided to go higher where there might be more snow, so on December 22 I headed for the high ridge north of the lake. Vern stayed behind to tend camp, since he had come along on this trip mostly for the outing and to trap and poison coyotes and wolves along Adams Lake. I took one dog, Spot, and left Stub in camp. With a two-months hunt in prospect, I didn’t want to wear out both dogs. I crossed the top of the ridge before nightfall and camped in a sheltered creek basin about six miles below the top, near Barriere Lakes. Just before dark, I had found three freshly killed and partly eaten deer carcasses, all dragged together in a thick patch of timber. This was highly unusual, and I knew there were plenty of cats around.

I carried no bedding, and depended upon a pile of boughs for a mattress and my packsack for a cover. I also cut a huge pile of wood so I could keep a large fire going all night. I must have been so tired that I didn’t wake up when the snowstorm started and my fire died down. If that cougar had kept quiet, I would have missed one of the most amazing and dangerous adventures I was to experience in over 30 years of trailing the big cats.

Spot had no idea what had made that cry. I had used her on many cougars, but she had never heard one call. She walked beside me completely unconcerned until that strong cat smell rolled into her nostrils. Then she threw back her head and let go with a bawl that shook snow from the trees for 10 yards in every direction. Then she was gone, her baying sound lost and lonely in the darkness.

When I think back now, it seems unrealistic to put a dog on a hot cougar track at night and in the middle of a snowstorm. But I was only 37 years old then and in the peak of physical condition. I’ve trailed cats under many adverse conditions, but never anything like that night. I couldn’t see more than two or three yards ahead, and the snow was falling so fast it was covering Spot’s tracks almost as fast as she made them. I could barely make out the big, round depressions in the snow where the cat had walked away from the fire. The cougar must have been too surprised to run.

Within three minutes, I could hear Spot telling me she had a cougar up a tree. I did the best I could, floundering along through the brush, practically feeling my way with Spot’s bark as my only landmark. I found her at the base of a big fir. I tried to shine the little light up into the branches, but it was useless. Then I got an idea. A big snag had broken down about 20 yards away. The six-foot stump was hard and covered with pitch. In about 20 minutes I had the world’s biggest candle lighting the whole area.

I looked up into the tree and finally made out two big glowing eyes. It was more than eerie with that stump thundering flame, great snowflakes flowing through the wavering light, and those big yellow spots suspended in the depths of the tree.

I fitted the Mauser to the stock, aimed toward the eyes, and squeezed off five fast shots. The cat tumbled out of the tree and lay where it hit. After carefully keeping my distance for a few minutes, I walked up and nudged it with my foot. One of the slugs had found a fatal spot. The cat was a big female about five years old. Several of my bullets had hit her in the neck and chest.

It seemed to be snowing even harder, and I had no idea where my camp was. I knew the only way I was going to find it was to back-track if I could. I dragged the cougar under a tree where I hoped I might find it the next day, untied Spot, and started following the snow-filled impressions which I hoped were the tracks I’d made coming to the cat.

I hadn’t gone more than 50 yards from the burning stump when Spot started acting up. I lowered the carbide lamp and took a better look at my tracks. Instead of oblong impressions under the new-fallen snow, there were clear cut, round impressions blotting them out. Another cougar had followed me right up to within 50 yards of the treed cat. I had often encountered cougars traveling together, so it didn’t seem too unusual to find this second track. My only problem was that if I didn’t find my camp before too much longer I might not find it at all.

Spot soon made up my mind for me. She began lunging and growling, and I could tell from her actions that the cougar was right in front of us. This was more than I had bargained for, but I let her go. Apparently she was almost snapping at the cat’s tail because within 250 yards the cougar treed.

Once again I found myself practically feeling my way through the night guided only by Spot’s bark. This time I found her leaping at the base of a bushy fir tree. I walked up and pushed the carbide light through the branches.

It had climbed just high enough to avoid Spot’s snapping teeth and there it sat, a great tawny blob in the feeble light with eyes glowing like two yellow coals. I checked the Mauser to make sure it was loaded. Then, holding the pistol in one hand and the light in the other, I lined up the sights on the cat. Had I known then what a chance I was taking I wouldn’t have been so bold, but I’d never had a treed cougar even act as though it might jump me. I squeezed off three fast shots and stepped back. The cat thrashed around in the tree a few minutes and then fell to the ground, dead.

I looked over the second cougar and found it to be a large male. He apparently had been running with the female. Judging from the color and length of the hair and the condition of the teeth, the cat was about five years old. A cougar seems to grow slowly through most of its life. Its hair gradually becomes shorter and a grayness develops around the head and neck. The teeth are the best indicators of age; they become badly worn and are often cracked and broken in a very old tom.

The snow hadn’t let up, and I still wanted to find camp. I was dragging this cat under another fir tree when I heard Spot bellow. I hadn’t realized she was gone, and it was even harder to believe that she was on the trail of a third cougar. This was a lot more than I had expected. I was getting wet and completely lost and had no idea where camp was or where I was. I had two dead cougars which I wasn’t sure I would ever find again, and now my dog was trailing a third. Little did I know that I had just got through the best part of what was to be a long night.

SPOT SOON announced that she had done her job and was waiting for me to get there and polish off another pussycat. For the third time I groped along, trying to shield my face from limbs that seemed bent and cocked, ready to whip me as I passed. I floundered for at least half a mile to reach Spot’s third victim. This cat was also just above the ground, and I could see it faintly with the carbide light. I aimed the pistol right between its eyes and squeezed the trigger. In an instant I knew I was in trouble. At the crack of the shot, one big yellow eye winked out. The cat jumped from the tree and was away in a flash.

For the next hour or so I went through one of the most nightmarish experiences of my entire hunting career. Spot would tree the wounded cat and I would go crashing toward her, raked by hidden limbs and tripped by hundreds of invisible snags. Then the cat would jump the tree when I approached and the whole thing would start over again.

Around and around and back and forth I slogged. I didn’t know if I would ever find my camp and was reaching the point of not caring. I just lunged on with a fanatical determination to finish off that wounded cougar. Finally, the cat stayed treed on a small leaning tree trunk. He was perched about 10 feet from the ground, spitting and snarling at Spot. Under any other circumstances I would have been far more cautious, knowing that a wounded cougar could easily prove dangerous. But I was too tired and exhausted to care.

I walked right up under the cat, shoved the pistol under its chin, and put a bullet through and out the top of its head. It was another big male, about six years old. My first shot had hit him squarely in the eye. The bullet had been deflected by the hard, bony shell around his brain, and had gone right on through and out the side of his head.

Nearing exhaustion, I knew I had to get back to camp and get dried out and some grub in me as soon as possible. From my memory of the lay of the land, I knew I was on the opposite side of the basin from camp. I threw the cat under a tree and started off in the direction I hoped might lead me to my campfire. Spot followed behind me.

Without her barking, the night would have been a complete void. I could have been on a wet, cold, lightless planet. My world was wrapped around me in the faint, flickering circle of light cast by the carbide. By an amazing streak of good luck, I hit some of the tracks I made earlier in the evening and somehow found my way to camp.

Sometime during my wanderings, Spot disappeared. If I hadn’t been so miserable, I would have been sure I was dreaming when I heard her sound off on another hot track. Somewhere she had found the tracks of a fourth cougar. By this time I didn’t care if she treed that cat on my shoulder. I just kept going until I found camp. I built up a big fire, dried my clothing the best I could, and ate some food.

Spot had treed her fourth cougar about a mile up the canyon. I could hear her faint tree bark bucking the sodden darkness. I could visualize her, leaping and yapping at the base of a tree, pleased with herself for such an outstanding performance. I hated to fail her, but I just didn’t have the strength to get there.

The snowstorm never let up. I got as dry as possible, brushed the snow away from my bough bed, and lay down, getting as much cover as I could from my packsack. I was so tired I could have slept hanging over a tree limb. It must have been about 9 o’clock when I finally woke up. My fire had died and I had nearly 10 inches of wet snow piled on top of me. If it had been cold I would have nearly frozen to death. But all that snow on top of my heavy wool clothing had provided a lot of warmth. Spot had finally given up and come back.

After a big breakfast, I went in search of my three cougars. It had snowed nearly 16 inches in all, and I could find absolutely no trace of my tracks made during the nightmarish chase.

I HAD NEARLY given up when I hit a fresh cat track. I was almost certain it had been made by the fourth cougar searching for its companions. I decided to follow.

Before the day was over, I was to undergo a second experience that stands out as one of the most unusual during a lifetime of cougar hunting. That cat had searched until it found each of its three dead companions. Then it had pawed the snow away from their bodies and had lain on top of the carcasses, I had only to follow the wandering tracks until all three dead cougars had been located. I have no explanation for this other than that the cat was lonely and confused by the sudden disappearance of its comrades.

I spent the entire day skinning the three cats and packing the hides and my grub back to a campsite at the top of the ridge in an old burn. It was nearly six miles but I took the whole works in one load, making it just before dark. I hung two of the skins on a low snag and used the third for a bed.

I slept long and well that night. I awoke early and got up with the intention of going back down the mountain to see if I might still find the fourth cougar. It had snowed about half an inch during the night, and I knew I wouldn’t have any trouble pick ing up the freshest tracks if the cougar was still there. I ate a huge breakfast and loaded enough grub in my packsack for another meal. Then I started back down the mountain.

I hadn’t walked more than 40 yards when I came to a big burned log lying flat on the ground. There, in a straight line leading out across the top of the ridge, were a set of pug marks on top of the fresh snow. The cat had followed me to the top of the mountain and had slept alongside the log all night. I am sure it had watched me for a while at daylight, and then walked away in plain sight without my noticing it.

I’M CERTAIN none of these cougars had I ever seen man or dog and had absolutely no fear of us. It was only Spot’s baying that put them to rout when I set her on their tracks. The fourth cat had gone north until it reached a strip of green timber about 50 yards wide. This timber followed a shallow draw and had somehow escaped the old forest fire. The cougar had walked to the edge and had then turned downhill following parallel with the near side.

I had just tracked it to the point where it turned when I heard a terrific commotion below me and across the draw. There were sounds of limbs cracking and then a sound as though someone were beating dried brush to pieces with a heavy club. I sneaked along, following the tracks about 200 yards.

The cat had turned down into the draw. The green trees were heavily loaded with wet snow, and the cougar had crossed through them and out into the burn on the other side. It had circled a small knoll and had crept to within 50 yards of a five-point mule deer that was eating some green alders. The buck had been facing downhill, and the cat had taken about five long jumps and landed squarely on his back, knocking him down. The noise I had heard had been the buck kicking and thrashing in the alders while the cougar held him by the back of the neck.

The cat had then dragged the buck back through the burn and down into the strip of green timber. I’m sure it let me approach to within 50 yards before it deserted the buck and walked into the brush. This was the first and last time I was ever within hearing distance of a cougar making a kill, but there was one thing about it that intrigued me even more.

In preparing to eat some of the buck, the cat had completely sheared a 16 inch circle of hair away from the left side of the carcass. The hair had been clipped as neatly and as closely as any pair of barber shears could have done. In addition, the cat had piled the hair in a nice little stack off to one side. A cougar’s front teeth match perfectly and the edges are razor sharp. Apparently, it had nipped this hair away in little tufts with those sharp clippers. I followed the tracks a short distance to get Spot away from the deer, and then I set her on the track.

I didn’t want to fight my way through the snow-laden trees, so I crossed the draw and had just reached he burned area when I heard Spot bark treed. I followed along the green timber for about a quarter of a mile until I reached a position opposite her homing signal coming from the draw.

THERE WAS the cougar standing on a leaning windfall some 15 feet above the ground. Although it was about 60 yards away, I decided to take a shot from where I was since I was afraid it might jump if I tried to get to a point under it.

I put the Mauser pistol on the stock and took careful aim. When the shot cracked I saw the hair puff on the cat’s ribs, but a little too far back. In an instant the cat was gone, and I could only follow the bellowing chase with my ears.

In about 60 yards Spot treed again. Once more the cat had climbed up a low, slanting windfall, and I knew when I walked up to the scene that I had a very angry female cougar to contend with. She was only about 10 feet from the ground, and a picture of absolute rage-eyes glowing, ears laid flat, lips rolled back from long, polished teeth.

Spot was doing her best to get a chunk of cougar between her teeth, and the cat was spitting vehemently, while taking vicious uppercuts in her direction. I walked up to within 15 feet and drew the handgun out of the holster, raising it at arms length with the barrel almost straight up.

In that instant, fate decided to throw in the final chilling touch to my greatest cougar-hunting adventure. A huge mass of wet snow dropped from directly above me and landed squarely on the upended barrel. I should have known better than to take my eyes from the cat, but I never thought she might jump me. I reached down, broke off a small twig, and inserted it into the pistol barrel. I was working out the snow when a sudden movement caught my eye and caused me to look up. The cougar had crouched and was already in the middle of an open-jawed, death-dealing spring.

She came sailing at me as if she’d been shot from a circus cannon—a heart-stopping vision of hate-filled eyes, white teeth, and hook-rimmed paws. In one instinctive lunge, I threw myself down and to one side. The cat sailed by, practically combing my whiskers with a vicious hooking swipe as she passed. If she’d ever landed on bare ground I wouldn’t be telling this story. But when she hit that deep, wet snow and tried to turn, she momentarily lost her footing. In the extra second it took her to get her feet gathered, I had time to half roll and twist to face her charge.

There was no time to worry about snow in the barrel. I thrust the pistol in her face and felt, more than heard, the staccato hammering as I ran a full magazine of slugs into her oncoming head and body. She died in midstride, falling within inches of my outstretched leg.

It would be foolish to say I wasn’t scared, but at a time like that the will to survive overcomes all fear. I was completely aware that I had come within a hairbreadth of vanishing in the Canadian wilds. Apparently, all the indignities I had inflicted upon this cougar were just too much. I had set my dog on her, killed her companions, taken a deer away from her, and then followed all this up by wounding her. Though I killed 10 more cougars on that one trip, and dozens more in the next 28 years, I never again had a cougar try to jump me.

I loaded the four skins and packed them down to Adams Lake that same day. It wasn’t until I reached the ranch of a family named Todd that I realized it was Christmas Eve. I spent the night there and returned to my own camp to join Vern on Christmas Day.

I still hunt a lot, but I haven’t hunted the big cats since 1957. It must have been one more quirk of fate to decree that I should get my last two near the head of Adams Lake that year when I was 65 years old. If I never take the trails again, I have a lot of thrilling memories, and this great experience sits right at the top.

This text has been minimally edited to meet contemporary standards.

Read more stories from the Outdoor Life archives:

- An Ontario Moose Hunt Turns Into a 10-Day Survival Ordeal, From the Archives

- Arrow for a Grizzly: A Classic Fred Bear Tale from the Archives

- My Lady Judas: The Wolf-Dog That Called In a Pack of Wolves for Frank Glaser

Or check out more OL+ stories.