The phone rang late one Saturday evening with news that the crew had cut a big cougar track. Several of the hunting team members were running cutlines, pipelines, and any other roads and trails through the woods to find out where the cat might be headed. Their question for me was, “Can you get here first thing in the morning?”

I immediately canceled my plans for the next day and started frantically pulling together my gear. I needed to prepare for running through deep snow, but also keeping warm if we caught up to the cat. The temperatures had been frigid for weeks, but the one-day break in the weather had given my crew enough time to cut a good track.

Cougar tracks can be difficult to find, but a big cat is especially challenging to track down. That’s just one of the reasons hunters like me almost always hire a guide for cougar hunts.

Cutting Tracks

I booked my hunt 14 months ago with Kelly Morton, who has earned a reputation for harvesting big toms. Morton had other clients scheduled before me and I patiently waited for a call to action. We had spent a couple of days “cutting” before Christmas, and a crew of avid houndspeople and hunters had been searching for “the track” since before the season opened Dec. 1. Cutting is a means of covering lots of ground to look for fresh tracks. This is usually done by driving logging roads, or any linear trails through the timber from before sunrise until dark. When there’s fresh snow, a crew will be out cutting all day, with everyone headed in different directions. A trained eye can spot a cat track quickly, and the size of the cat is determined by measuring the width of the impression left by the foot pad.

The first week of the season saw poor tracking conditions. Then once it started to snow, it seemed like it never quit. Temperatures dipped to -40°F with windchill, making the hunt challenging for dogs and people. Snow accumulated quickly and covered new tracks as fast as cats laid them down.

Mountain Lion Management

Cougars are an apex predator, and incredibly efficient hunters. Studies have been ongoing for decades to learn more about the big cats. Researchers use radio collars to monitor their daily movements, hunts, and kill rates. A radio-collar study out of Oregon found that cougars killed an average of one ungulate per week. In the areas of Alberta where I hunted, their prey is primarily deer and moose. The impact of a big cat adds up fast. And when it’s extremely cold, the cats need to kill more often so they can eat fresh, not frozen, meat. It’s been shown that a single cat can kill up to eight ungulates a week depending on its habitat and the conditions. We don’t hunt cougars to reduce competition with hunters, but to maintain a balance among furbearers, ungulates, habitat, and humans. Under careful management, which includes hunting, cougar populations have increased in Alberta (there are an estimated 2,000 to 3,500 cougars in Alberta), and they continue to expand into new regions.

Alberta uses a quota system to conservatively manage cougar populations and harvest. The province has 32 Cougar Management Units, and each CMU has a quota for male and female cats. All harvests must be reported. When a quota is filled, there is no more hunting in that unit. The zone we were hunting has a quota of two male cougars per year. There are other seasons where dogs are prohibited. Hunting wild cats can be a controversial and emotional subject for some folks. In Colorado, for example, newly proposed legislation that attempted to ban hunting for mountain lions, bobcat, and lynx was just defeated. In Alberta, many folks recognize how hunting helps conservation of the species, and it’s closely managed to support the population and its role within the ecosystem.

In the Hunt

I left home in the dark and started driving, even though I didn’t know where my final destination would be. Chelsey Anderson, Morton’s life partner, called with updates to let me know the crew was freshening up the track. When they found a potential starting point, she would send me a waypoint to navigate the backroads where they would be waiting. The team had covered more than five miles of mature boreal forest before deciding there was an excellent chance to get the hounds on “Old Bigfoot.”

The snow was deep and a fresh coat covered the road surface. As I wound farther into the backcountry, I spotted the tracks from a pack of wolves. Wolves can ruin a human’s cat hunt, as they will track a cougar with the hopes of stealing its kill. The smoking-hot tracks wandered down the center of the road for at least a mile before heading off into dense cover. I still had about six miles to go, so I shrugged off the wolf sign and kept driving.

Soon I found trucks parked on the side of the road, where it turned into a rough trail. Several hounds were on leashes, and people were scurrying around getting backpacks organized and outfitting every dog with a GPS collar. Anderson met me with a big smile and quickly introduced me to the rest of the team. I had barely pulled my warm clothes on by the time the first dogs were set loose on the big cat tracks. Smiles erupted on everyone’s face, and the chase was on.

The gents I was running with were big boys, and they cut a trail through the deep snow like a team of draft horses. Younger dogs were coming up behind us, while the older, experienced dogs already ahead with noses full of cat. I trudged along as fast as I could, pushing through the snow up to my knees. It was immediately clear that cougars don’t travel in straight lines. The big cat followed ridges before easeing over deadfall that either tripped us up or acted as barriers. But still we marched steadily toward the sound of the singing hounds.

In a bit, we stopped and watched how the chase was unfolding on the GPS. The cat made a big sweep around a lake and headed down the far shore. We decided to take a shortcut and cut around the bottom end of the lake to pick up the tracks. Unfortunately, the cat turned away and led the dogs in the opposite direction. Twice, the old tom gave the dogs the slip, but the experienced hounds circled and picked up the scent again.

We had already been tromping through the deep snow for a mile when we cut across to a trail to meet the rest of the team. The dogs were barking “treed.” The increased excitement and higher pitch of this barking is noticeable even to someone new to hound hunting, and it meant they had finally cornered the cat on the ground or in a tree. We took snowmachines and a quad on tracks around the lake to close the distance.

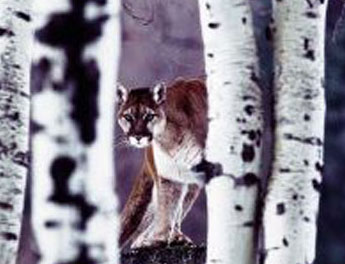

The hounds were singing their victory song and pacing around the base of a big aspen. In the upper branches was a giant old cat with ears extending from the side of his head. The cat’s tail looked as long as his body, and the front legs rippled with toned muscle. We looked the cougar over carefully and knew it was a mature tom. He seemed to ignore the dogs and hunters below.

We quickly discussed shot placement, and picked a gray patch of fur in the armpit of the lion that would ensure my broadhead would find vitals. I cocked my crossbow, a TenPoint Nitro 505, and settled it on my shooting sticks. The shot was at an extreme angle, and the tangle of tree limbs fwould make threading an arrow even more challenging.

My bare fingers were seizing up in the bitter cold, and when I slid the safety off, I checked it visually, too—I could not feel it with my fingertips. A deep breath helped me steady the bow, and I placed my crosshair on the tiny gray spot we had discussed. I slowly squeezed the trigger until I heard the whack of the broadhead hitting home.

The shot was perfect. The cat slumped over, getting hung up in the tree for 15 seconds. The dogs went crazy, anticipating the cat finding its way to the ground. Seconds later, the old lion crashed to the ground through a tangle of branches. When I saw the cat on the ground, I realized it was much bigger than I’d thought. I was in awe.

Hunting with hounds is a unique experience, and I consider the entire Kelly Morton Hunting team responsible for our success. The chase is a big part of the hunt, but so is cutting, managing dogs, and knowing how to judge tracks long before the chase ever begins. Morton also runs bobcats and lynx in British Columbia, and someday I hope to be back on the trail of another cat with his well-trained hounds and hunting team.

The Final Word on Cougar Meat

Cougar, or mountain lion, meat is delicious. I would compare it to lean pork, but sweeter. Folks who dispute this have likely never tried it. The meat is a bonus to the hunt that should not be overlooked. Having a freezer full of fresh cougar is exciting to a wild-game cook like me, since it’s been years since I’ve had enough cougar to share with family and friends. I will cure and smoke the hams, prepare cutlets for schnitzel, and save the tenderloins for a special dry rub and the pellet smoker. I’ll grind meatballs, loafs, or special fresh sausage that will last through the winter. And with each bite, I’ll get to relive the hunt.