This story, “Scarface,” appeared in the Dec. 1967 issue of Outdoor Life.

When I got my grand-slam ram on Nevada’s Desert Game Range in November 1963, I was convinced my good luck was due to the presence of my wife, Kay, on the hunt (see “The Grand Climax,” OUTDOOR LIFE, May 1965).

During the height of my elation, I promised I would guide, pack, and even cook for Kay if she was ever lucky enough to get a tag. She accepted my pledge smilingly. “I won’t forget the offer when I get my tag next year,” she said.

In the spring of 1964, Nevada’s Fish and Game Commission announced that there would be no hunting in the sheep range that year. The dates for the next hunt were to be February 27 through March 14, 1965, and a lottery was to be held in the fish and game offices in Reno during November 1964, for 27 resident and three nonresident permits. After sending in her application and money order for $10, Kay seemed calmly confident that her name would be drawn, even though she knew that the desert bighorn is one of North America’s most coveted big-game trophies and that her chances for a tag were less than one out of seven. A woman with her mind made up, however, has a strange way of overcoming probability. On the night of the drawing, my wife’s name was the first one pulled from the hat.

Kay was born in Colorado Springs, Colorado. After her school years, she trained to become an X-ray technician. Her first job was with a clinic in Reno, Nevada, and it was there we met. We still live in Reno. Our original attraction for one another will remain a mystery, for I’m an enthusiastic hunter, and prior to our marriage in 1954, Kay didn’t know a .30/06 from a DC-7.

Those were the days when I was a brand-new doctor, a general practitioner, setting up my first solo practice. The demands of medicine didn’t dampen my life-long love of hunting, however, and Kay caught the bug from me as easily as a schoolboy catches cold. She’s learned to be a good hunter, and has collected mule deer, antelope, and a record Barren Ground caribou. She has accompanied me on all of my big-game hunts, and she shared my enthusiasm for sheep hunting even though she had never shot a sheep. Though she’s a good, cool shot, we had dry-firing exercises every night in our living room for the following three months. She used my custom Mauser .270 fitted with a 4X Pecar scope, the outfit I had used on all my mountain sheep. Kay learned to work the bolt and get into shooting position faster than Annie Oakley ever dreamed possible.

We spent every spare hour in the hills near our home shooting at targets, rocks, and jackrabbits. I was loading Winchester brass with 55 grains of No. 4350 powder behind Sierra 130-grain boattail bullets. The recoil was mild enough for Kay, and her accuracy became superb. She learned to pick off a sitting rabbit at 200 yards with almost every shot.

As the season drew closer, I became increasingly excited while Kay remained curiously nonchalant. She kept reminding me of the desert sheep I had scored for a hunter the year before (I’m an official Boone and Crockett measurer). She wasn’t going to settle for anything less. That particular ram was a magnificent old-timer that had heavy, chipped horns and a callus growing out of the bridge of his nose. He scored 161 2/8 points — great for a desert sheep.

I told Kay about the odds against getting a big sheep. The Desert Game Range occupies 2-million acres. Its sheep population, including ewes and lambs, is estimated at 1,500. If half were males, probably less than half of that number would be legal rams. The number of big busters would be smaller still, and the chances of finding one would be much less than hitting a number straight up on the roulette wheel. The excitement and anticipation two weeks before the hunt had set the stage for the disappointment which came in the form of a special-delivery letter. The chairman of a national hospital committee, of which I am a member, was calling a special meeting in Houston, Texas, for March first. I had the phone in hand and was about to tell the chairman what he could do with the meeting when my wife’s complacency deterred me. She found that there was a nonstop jet daily from Las Vegas to Houston. She argued that we could easily spare one day out of the hunt and, furthermore, she had a friend in Las Vegas she wanted to visit. I mumbled my assent and let it go at that.

On February 26, the day before the sheep season opened, we connected our travel trailer to our four-wheel-drive station wagon, said goodbye to our three little ones and my mother, who had agreed to be our baby sitter, and started on our 450-mile trip south. We reached Indian Springs by bedtime and camped beside the highway. In the morning we filled our gas and water cans and drove the remaining 25 miles to the Corn Creek checking station where we were greeted by Dr. Charles Hansen, big-game biologist for the Desert Game Range.

“Hi, Bob,” he said, “Hi, Kay. So you’re the hunter this time. You brought along your guide, I see. After you get the trailer parked, I want you in the office to take a test we’ve devised for hunters.”

Dr. Hansen explained later that the reason for giving the test was to make sure that the sheep hunters knew what a trophy ram looks like. A legal ram is one that has horns with a three-quarter curl or better, but the fish-and-wildlife people want the hunters to take only the old rams if possible, leaving the younger ones for propagation. The test included questions about the size and weight of mature mountain sheep, how to estimate age of the live animals, Boone and Crockett scoring, and where rams are most likely to be found. Some ram and ewe horns were set up in the office for demonstrations.

I told Dr. Hansen that Kay and I would be able to hunt only that day, since I had to leave for Houston on the next morning, but that we would be hunting again after I got back. The specter of my trip to Houston dampened my enthusiasm, and I hunted fretfully. Neither of us saw a sheep. The trip and the meeting went off like clockwork, however, and Kay was at the airport gate to meet me the next night.

“Now let’s get that ram,” I said. We drove the station wagon down the Las Vegas strip, oblivious to the lights and entertainment attractions, and went straight to the Corn Creek station and our trailer.

We were up and ready by 6 o’clock next morning. By that time all the other tag holders had checked in and had hunted the well-known spots. Dr. Hansen told us that even though the season had been open for three days, only one ram had been checked in and that the other hunters had seen few sheep. Kay and I selected a spot 45 miles to the north, and we told Chuck we would take our trailer to that spot and hunt from there. We reached our destination after four hours of dodging rocks and washouts, had lunch, and studied our maps once more. We agreed to try to drive the station wagon loaded with a light camp seven miles across the trackless desert to the western escarpment of the Sheep Range to a place called Sheep Springs. I picked our way with extreme caution, and it was all four-wheel-drive, low-gear work. In rocky areas where our tires left no tracks, I marked our way with stone monuments so we could find our way back. Many of the washes we tried ended in impassable jumbles of rocks or steep banks, and we had to retrace our trails and tr.y new routes. In some spots, especially on the ridges, the going was easy, and we wove in and out between the Joshua and mesquite bushes with ease. We climbed steadily, and 90 minutes later we parked the wagon on the face of the Sheep Range.

I carefully glassed the washes and alluvial fans that flowed from the mountain before leaving the station wagon. Rams are sometimes found grazing or bedded some distance from the main slopes. There was no vapor or haze, and the only factors that limited visibility were the condition of one’s eyes and optical equipment. I blocked the wheels of our wagon, made sure the cap was tight on our gallon jug of water, and then helped Kay put on her packboard. I squirmed into mine and led the way northward along the face of the mountain.

By the time we had gone three miles, the sun was sinking behind the hills. We moved slowly, glassing each wash. As we reached the top of a ridge between two large washes, a fresh sheep track in dry ground caught my eye.

“Look at those tracks, Kay,” I said. “That sheep’s traveling ahead of us. Fresh ones too.” Kay remained silent, walked a few steps, stopped and glassed the floor of the wash, then studied the canyon above it. I considered the direction of the tracks, went a few more steps toward the ‘floor of the wash, and stopped again. I had gone just three steps too far. At the mouth of the canyon, hugging its right wall, were two rams one behind the other, and they were looking right at us.

“Down,” I whispered. Kay crouched next to me and found the sheep in her 6 x 30 Bushnells. “We’ll sit here for a bit,” I said. “Maybe they’ll start to feed and we can go back the way we came and get out of sight.” It was probably a stupid thing to suggest, but I didn’t know what else to do. The sheep just stood there, a safe 600 yards away, staring at us.

We waited for what seemed like an eternity. Finally, I got on all fours and crawled back over our trail, motioning for Kay to follow. Once on top of the ridge, we were out of sight of the rams, and we took off our packs. We made a dandy sneak that should have put us within 200 yards of the animals, but when we peeked around the last obstacle there was nothing to see but beautiful desert scenery. We never saw those sheep again.

We spent the night on the desert 50 miles from the nearest human. After our supper, the gentle breeze swirled the pungent smoke from the remains of the greasewood fire, and I pulled the top of my sleeping bag tightly around my neck. Sleep seemed unimportant, for I was dazzled by the millions of twinkling stars in the black sky. The breeze and the embers slowly died, and I listened to the voice of a distant coyote. The affairs of my daily life seemed like bad dreams. The lights in the sky were hypnotic, and my breathing became deep and regular. We had breakfasted and rolled our beds before the sunlight found our canyon. I put lunch and the water on my packboard and we started out again, still going north. We glassed washes, ridges, alluvial fans, rocks, Joshua forests, and canyons till noon, then stopped to eat. On our way back to our camp of the night before, we walked up several of the canyons but found nothing except tracks and droppings. Kay picked up the bleached skull and horns of a young ram, but that’s as close as we came to seeing another sheep. We picked up our camp equipment and made the trek back to the wagon by 4:30.

We drove back to the mountain the next morning, then hunted on foot to the south. In the mouth of one canyon I found a huge set of horns still connected to the skull, held them up admiringly, and called to Kay, “How’d you like to find one like this alive?” She gave a low whistle as she hefted the specimen which later scored 160 Boone and Crockett points. We took some pictures, tied the horns on my packboard, and continued hunting. It was dark when I parked the station wagon by the trailer.

Next morning we drove over the primitive road to Cabin Springs, which was six miles south of where we had hunted the day before. We took packboards and a light camp again and walked along the face of the mountains to the south. All the tracks and droppings were old, and as we made camp that night I began to worry that we didn’t have as much time as I’d thought.

We were up at dawn as usual, ate a breakfast of hard-boiled eggs, sweet rolls, and hot coffee, and continued hunting to the south. The farther we went, the less abundant the sign became. “No use continuing in this direction, Kay,” I said at lunchtime. “Sheep are clever, but they can’t fly. No tracks, no sheep.”

The long hikes were beginning to tire us so we decided the next day to explore with the station wagon and walk short distances into areas that looked promising. We found an old set of tire tracks going along the east face of a mountain south of the trailer, and as we picked our way along the trail we got out frequently to explore the draws and washes. The mountains were more barren and forbidding than the main Sheep Range, but the farther we got from the trailer the more tracks and droppings we saw. It was a paradox to find so much fresh evidence there, for our maps indicated that the nearest water was 15 miles away.

Our seventh hunting day found us on a nameless peak south of the trailer. Some of the washes were literally cut up with tracks, while others had none. It was in one of those sterile canyons that my heart did a flip-flop, for in the soft dirt were the fresh tracks of a running sheep.

“Think we spooked him?” asked Kay as she examined the tracks.

“Could be, but he doesn’t seem to be running hard. Let’s stay with the trail and see if we can figure out where he went.”

The tracks were a snap to follow for a short distance because the dirt was unusually soft. They soon angled up into rocks, however, and after 30 minutes I gave it up.

“Looks as though that sheep is headed around the end of the hill, Kay. Why don’t we go over the top and see if we can cut his track on the other side?” I tried to sound optimistic, but I was convinced we wouldn’t find the sheep or more tracks. As we neared the top of the saddle, I stopped and glassed the next hill. Nothing. I went on to the top, then started down.

“Stop, honey, a ram — down in the bottom!” The urgency in Kay’s voice caused me to squat down quickly. “He’s a big one too. Too far for me to shoot, though. What’ll we do?”

The ram was grazing in the bottom of the canyon 400 yards away, and Kay was right about his size. His color blended perfectly with the background. Had it not been for Kay’s unusually sharp eyes, I probably wouldn’t have seen the sheep till he moved.

“That ram doesn’t know we’re here,” I said. “We’ve got to get up and move sometime, and no matter which way we go that sheep could look up and see us. There isn’t enough cover up here to hide a horned toad, but there’s a big rock outcropping down the hill halfway to the sheep. If the sheep doesn’t look up before we get there, we’ve got it made.” I wished that the decision wasn’t mine to make because I had a premonition that no matter which way we went, it wouldn’t work. “What do you think?” I asked Kay.

“You’re the guide,” Kay answered as she nudged the small of my back with the toe of her boot. “Let’s get going.” After the first 50 yards, I thought we were going to pull it off. After a few more steps, though, I inadvertently kicked an orange-size rock and it rolled down the hillside a few feet. The ram lifted his head and looked right at us.

The three of us remained motionless for a long 20 seconds. Then the sheep put his head back, bounded effortlessly up the opposite hillside, and went out of sight over the ridge.

Kay flopped down, picked up a handful of gravel, and flung it down the mountain. “Did you see how heavy his horns were at the base and what a beautiful flare they had?” she asked. “They were just w,1at I had in mind.” This was the first comment Kay had made on the entire hunt that even hinted of dejection. “Think we can find him again?” she asked.

“He’s not badly spooked, and we didn’t make the mistake of shooting at him,” I said. “He might not go far, and with a fresh start in the morning we just might find him.” I didn’t believe a word I said.

Next morning my eyes ached from a week of searching and my shoulders were getting sore where the straps on my pack rubbed. Just beyond the spot where we had seen the sheep the day before, we found another set of ram’s horns detached from a bleached skull. We dubbed the little rocky prominence nearby Horn Point, and we left the horns there so we could find them on the way back. We had traveled some distance into one of the main washes that penetrated the steep mountain-side when my sharp-eyed companion said, “Wait a minute, Bob, there’s a sheep up there.”

I was skeptical and thought that surely my wife was looking at a rock or bush. We had been similarly fooled many times. After seven days of practice, we had our arrangements for locating objects down pat, and Kay zeroed me in perfectly on the buff-colored, four-legged, white-bottomed something.

“It is a sheep,” I muttered in disbelief as I sharpened the focus of my 8 x 30 Bausch & Lomb binoculars. “I can’t tell if it’s a ram from here, though. Let’s get out of sight and set up the scope.”

I laid my 32X Bushnell spotting scope over my hat and focused on the left slope near the end of the canyon. The sheep was a legal ram, but what I couldn’t see were two more rams lying among the rocks directly below him. “The third time has to be the charm,” I mumbled as I devoured the sight of the first ram through the scope. “We won’t goof this time.” Kay pushed me from the eyepiece so she could see.

“Our only hope is to crawl most of the way, hugging the left bank of the wash. Think you can do it?” I asked. She returned my smile with the reckless wink of the heroic fighter pilot about to take off at dawn with his battle-weary squadron. We ate half our lunch and had a long drink from the canteen. I shed all unnecessary equipment, dropped to my hands and knees, and led off.

As we closed the distance, bits of the hillside came into view that had previously been hidden, and along with the new geography, more rams kept popping into sight. At a distance of 600 yards, we could see every inch of the area, and we counted nine trophy rams. The sheep took turns feeding, watching, and lying down. They showed no suspicion that anything was wrong, and we had time to study each animal carefully with our binoculars.

Our attention kept returning to one sheep that did more than his share of lying down and never took his turn on watch. He was obviously the old leader. His horns were heavy clear to their points, which had been broomed from years of combat and digging in the desert. His scarred and battered face personified a rugged and noble past.

We squirmed silently ahead until we reached a spot which I guessed to be 200 yards from the sheep, but which was out of sight under the bank.

I turned for a last look at Kay, marveling that she had come this far without complaint. She was lying at my feet, pressed tightly against the bank. Her cheeks gleamed with dampness, and her sides moved with even, deep respirations. She cradled the .270 in the hollow of her elbows, military style, and sucked in on her lower lip.

We crawled to the top of the steep bank and lay prone in full view of the sheep. Their surprise kept them standing in motionless single file, staring down at us. Kay wriggled into position, worked the bolt smoothly, and snapped on the safety. The training in the living room is paying off, I thought as I skidded my rolled up jacket and my hat under the barrel. I glassed the sheep one last time.

“Old Scarface is the third from the left,” I said. “He’s standing facing you and you’ll have to take him in the brisket. Can you get him in the scope all right?” I was beginning to shake with excitement.

“The barrel is just a little low. Roll up the jacket a little tighter,” Kay said calmly. As I re-rolled the jacket, I whispered something about the sheep not standing there all day and heard her say, “There, that’s just right.”

“Center the crosshairs right on the middle of his chest,” I urged. Kay snapped off the safety. “Remember, now, squeeze . . .” Bam! The big ram sat back on his haunches but didn’t go down. He regained his feet, made three good jumps down the bank, and then crashed down like a dropped tray of dishes. The younger rams bounded up the mountain, slowed to a walk, and stopped to look back at the old one.

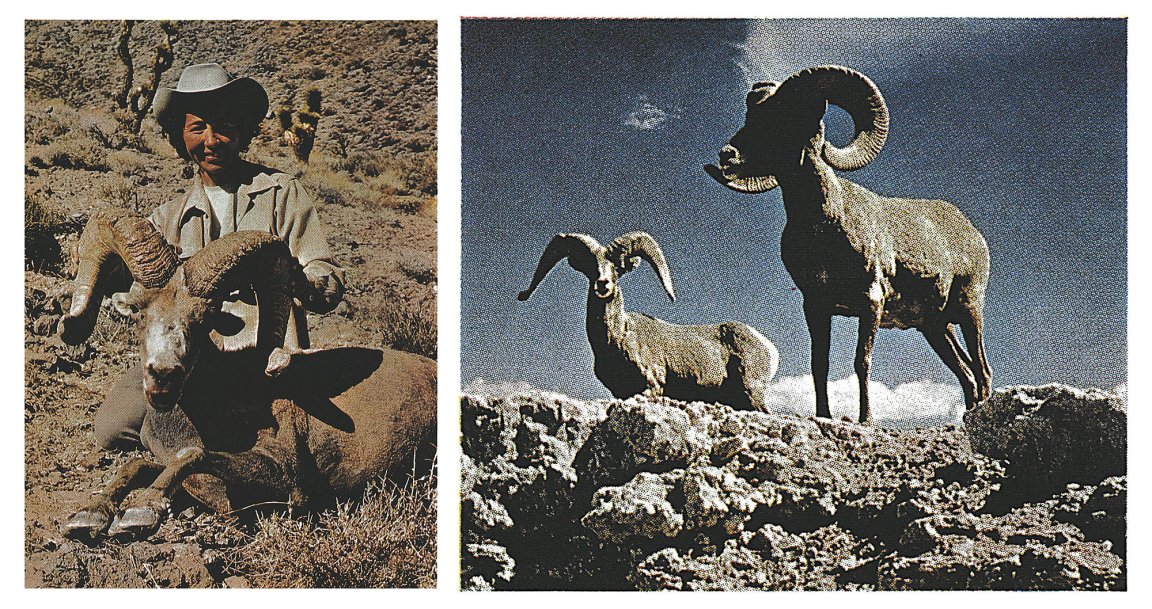

I got to the ram first, lifted his massive head, and let out a yell that I’m sure was heard in Las Vegas. ,The bullet had taken the ram in the center of the brisket and then had blown up in the chest cavity. It had been a quick and humane death for the old gentleman. Kay pushed her broad-brimmed cowboy hat to the back of her head, wiped her brow with her shirtsleeve, and sighed, “By golly, I did it, and look at that face! Just what I wanted, callus on the nose and everything.”

After dressing the ram, I packed out the head and cape, Kay carried the gear, and we both laughed hysterically all the way back to the wagon. We packed out the meat the following day, then jubilantly drove the 45 miles back to the checking station.

Dr. Hansen was beside himself with happiness when he saw Kay’s trophy, and he heaped congratulations on her. “You really earned your ram,” he said. “I know a lot of men who wouldn’t have stayed with it as long as you did.”

After the hunt, I learned that only eight resident hunters and one non-resident had taken rams in the area we hunted. I scored Kay’s ram at a conservative 166 points, or 16 points more than the one I shot in 1963.

Restoration Efforts for Sheep, in the 1960s

If you’ve given up hoping for a desert bighorn, cheer up. The Nevada Fish and Game Commission has a transplanting program for native bighorns. In 1936, only 300 desert sheep remained in Nevada. But then the 2½-million-acre Desert National Wildlife Range was established. Some 20 years later, 1,700 sheep roamed the range.

The desert range had reached its carrying capacity for sheep. More trophy rams died of starvation and disease than were taken by hunters. The Fish and Game Commission, of which I’m now a member, realized that the sheep would not increase unless they could be reestablished on some former ranges.

Trapping and transplanting sheep has been done in Wyoming, Montana, North Dakota, Washington, and Texas. The most stirring example, however, began in Oregon in 1954. Twenty California bighorns from British Columbia were put in a 600-acre enclosure where they reproduced. Two releases of the progeny have been made in Oregon, and there have been trophy hunts.

Oregon’s success breathed life into Nevada’s program for desert sheep. Dr. W. Glenn Bradley of Nevada Southern University made a proposal. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service personnel at the desert range would trap sheep. The Nevada game department would then truck them to a holding area where they could reproduce. The progeny would be transplanted elsewhere.

The commission was skeptical about obtaining funds for transplanting an animal with an uncertain future. For instance, the minimum cost of a large enclosure for the sheep was $40,000.

The Fraternity of the Desert Bighorn helped. This voluntary group’s 235 members gave funds with which to get the project started. The Boone and Crockett Club and the Fleischmann Foundation followed with gifts. Harvey Gross, owner of Harvey’s Wagon Wheel, donated the proceeds from a buffalo barbecue. These contributions and gifts from individual sportsmen came to over $11,000. That was enough to commit $30,000 in federal funds.

Then came the offer of a 1,200-acre enclosure site from the Hawthorne Naval Ammunition Depot. The Mt. Grant site is in good sheep country, and the enclosure is being built.

At the desert range, a two-acre trap is ready at Wamp Springs. The trapping will be under the supervision of Dr. Charles Hansen, chief biologist at the range. The sheep will be trapped by luring them to water during the hottest part of the summer.

The electric switch that operates the gates of the trap must be manned at all times during trapping. Dr. Hansen and his crew may stay in the blind for days before sheep come to drink.

Another project is starting. The plan is to move California bighorns late this year from Oregon to an enclosure in northern Nevada. Transplants from the progeny of this herd will be used to reestablish the California bighorn in Nevada where it was once native.

In 10 years, wild sheep may be hunted in parts of Nevada where they haven’t been seen since the 1860’s.