This story, “I Was the Dog,” appeared in the December 1967 issue of Outdoor Life.

I CAME HOME from work in a die plant in the village of Holly one Saturday noon in January of 1950 to find my 80-year-old uncle, Clarence Pittinger, waiting in the living room. He had walked the five miles into town from his place on Buckhorn Creek. He wasn’t carrying the sack in which he usually toted a few groceries home, and I guessed he had something special in mind.

He came to the point at once. “How’d you like to kill a fox?” he asked.

It was a fine winter day, sunny and crisp, and there had been a fresh fall of snow the night before, just enough for good tracking. It was the kind of afternoon when any outdoor activity is better than none, and I took the bait.

“I’d like it fine,” I told him.

“Get your shotgun and take me home,” he said. “I found a fresh track, and we can get him easy.”

I should have smelled a rat, and I knew that this kind of fox hunting called for more hard walking than an 80-year-old man was likely to do. But it was something I had never tried, and it sounded exciting, so I didn’t bother to ask him any questions. We drove out to Clarence’s house and left the car. On the farm of a neighbor a short distance away, he led me to a haystack. Sure enough, a fresh fox track went to the top of the stack, and a bed showed where the fox had lain, enjoying the winter sun. A track also showed where he had gone down on the other side and trotted away.

“You just follow that track and you’ll get him,” Clarence instructed me. “He’ll go through a lot of rough places, and the walking’s too hard for my game leg.” He had been having trouble with enlarged veins.

Looking back on the affair afterward, I remembered something close to a twinkle in the faded blue eyes at that point, but I didn’t give it any thought at the time. Remember, I had never sampled this brand of fox hunting. Clarence tramped off across the fields to the east, and I took the track. That old uncle of mine died last winter at the age of 94, the last of a breed, at least in our community. Let me interrupt the fox hunt while I tell you a little about him.

The family settled among the hills and lakes and marshes of Oakland County, in southeastern Michigan 50 miles from Detroit, right after the Civil War. They were pioneers, and up till the end of his life Clarence kept to the ways of his boyhood, ignoring all the sweeping changes that went on around him.

He lived all his life in the house that was built when he was a young boy. Oxteams had hauled the logs to a neighbor’s sawmill to supply the lumber. He never married, and the last 30 years or so after his bachelor brother Charlie died, he lived alone and did his own housework.

He never had a well. His water came from a cold, clear spring between the house and the creek. When he wanted to go somewhere, he walked. He never owned an automobile, a radio, or a television set. He had no telephone, and to the end of his days his house was lighted with kerosene lamps.

He grew his own tobacco in the same garden where he raised tomatoes and sweet corn and melons. He cured his tobacco himself in a small shed. Store-bought tobacco had no taste, Clarence complained. Friends who sampled his, even including men of his own generation, cooled their smarting tongues and said they were not surprised that the commercial kind failed to satisfy him. He was the last of the bee hunters in our community, and I’d give odds he ate more wild honey in his lifetime than sugar. He used a small homemade box with upper and lower compartments and sliding lids. In the fields late in the summer, he’d trap two or three bees in the box. Then he’d give them time to load up from a small comb of honey in the lower part, set the box up on a post or stump where he could watch the departing bees against the sky, and open the upper lid.

Carrying full loads, the bees would make a circle or two and then line out for their hive. If they were from a wild swarm, that would be in a hollow tree. If the line of flight did not lead in the direction of some beekeeper’s colonies, Clarence would move to a second location, maybe half a mile off to one side, and repeat the procedure. Where the two lines of flight crossed, the swarm had to be. It was no trick to watch bees coming and going in order to locate the tree itself.

Later in the fall, when the year’s full harvest of honey had been gathered by the bees, the tree would be cut down after the bees had been stupefied with a sulfur match, also homemade. Strips of rag were dipped in molten sulfur and then wrapped tightly around the end of a stick. Lighted, the match burned slowly and gave off enough fumes to take care of an entire swarm.

The honey in those trees hung in long, clean comb sections tapering from top to bottom. Sometimes they were two or three feet in length. The tree was cut after dark when the swarm was inside and quiet. Many an autumn night, Clarence and his brothers lugged home a washtub full of wild honey from a single tree.

I still remember one of those nocturnal forays. A neighbor who went along was licking honey from bits of bark and wood, but he mistook a honey-drenched live bee for such a morsel and popped it into his mouth. His speech was thick for days.

Clarence made much of his living from his trapline, by growing ginseng, and by selling cordwood. The trapline was not in remote wilderness either, but in farming country that had been settled and cleared before he was born. There were still plenty of skunks, muskrats, weasels, and mink left, however, and a good supply of coon and fox at times, and he knew how and where to take them. His annual fur catch was always the biggest in the neighborhood. He was frugal. Not that he had to be, for he had more than enough money to see him through his old age. He preferred it that way.

Uncle Clarence kept thin splints of dry tamarack on a shelf over his stove and used them to light his pipe in order to save matches. He used one match each morning to start a fire in the old wood stove. So long as he was in the house, he got his pipe going by first lighting a splint in the fire. Then he laid it up for next time.

He made his own cider and wine with a hand press of his own manufacture from wild apples, grapes, and elderberries. If he wanted a roof for a shed, he cut poles for rafters, mowed wild hay in the marshes with a scythe, and piled it on. The thatch was waterproof and lasted for several years.

When he cut stove wood, the sticks were all of a length, and he stacked them as painstakingly as a bricklayer lays his courses. When he was past 75, he harvested an entire field of hay with no equipment except a scythe, a hand rake, and a fork. He cut the hay, raked it into cocks, and carried it to a stack in the center of the field a fork at a time.

And all this was done within 50 miles of downtown Detroit and — in recent years — hardly more than five miles from a modern expressway that runs much of the way from Lake Superior to the Florida Keys. He belonged to another day, when independence and self-reliance and the freedom to live as he chose were a man’s most cherished possessions. He kept faith with his beliefs to the end.

His favorite sport, one that he and his brothers Charlie and George must have learned from their father or mastered early on their own, was taking a fresh fox track without dogs and following it until they caught up with the fox.

It was a hard way to hunt and often involved a hike of 15 or 20 miles in a day, but it paid off in excitement and fox skins. Two or sometimes three men hunted together. They’d find a track, preferably on new snow so they could be sure the prints were fresh, and stay on it. If the track led down into a swamp or brushy marsh, or toward a gullied, weed – grown hillside (places where the fox was likely to lie up for the day) one hunter circled ahead and waited at the most likely crossing place. From long experience, the Pittengers knew exactly where that would be. The second man then came through on the track.

Sometimes the one who jumped the fox would get the shooting; sometimes it would be the one who waited on a stand. Many times the fox did the unexpected and nobody got a shot. When that happened, they went on walking the track and repeating the performance. Most days, they’d be on the way home with another fox pelt before the winter dusk settled over the hills. By the time they reached middle age, Clarence and his brothers had taught younger men in the neighborhood the tricks of this rugged business of fox hunting without hounds. (“Walking the Tracks,” in OUTDOOR LIFE, February 1962, described the method in detail.) There’s a small group that still does it now and then, but I was never one of them.

I had hunted rabbits with my old uncle a few times, but for one reason and another, maybe because I never thought I wanted a fox that bad, I had avoided joining his fox hunts until that winter when he was 80.

I took the track that day, as I said earlier. The fox crossed an open field, made an abrupt turn, and went down into a big willow swamp along Buckhorn Creek. At the border of the swamp, he had turned aside and made a brief stop, probably looking back along his track to make sure the neighborhood was healthy before he went into the grass and willows to lie down. At that time nobody was following him. He had left the haystack before Clarence found his track in the forenoon, so he saw nothing to worry about, and his track showed it after he got into the swamp.

He trotted along in a businesslike way, keeping a fairly straight course except when he detoured around thick tangles of brush or turned to sniff at a clump of brown swamp grass that lifted above the snow. He crossed rabbit tracks and mouse tracks without paying any attention to them, and little as I knew about fox hunting and fox behavior, I decided he was looking for a place to lie down. I was right.

I had trailed him for half a mile when I found where he had gone into a patch of cattails, and in the middle of the patch, I came on his bed. He had left his bed at a dead run, which meant he had heard me coming. When I laid the back of my hand in the bed, the dry stems were still warm to the touch. I had come close to getting a crack at him, I told myself.

Actually I hadn’t come close at all. The swamp cover was so thick there that I couldn’t have seen him if he’d jumped 10 yards in front of me, but I didn’t stop to figure that out right then.

He knew I was after him now, and that meant he’d be more careful, but Clarence had told me I could kill the fox if I stayed on the track. I still believed it. I knew others had done it plenty of times, and I had hunted enough birds and rabbits to think I was just as crafty and skilled a hunter as they were.

About that time I began to notice that some of the stretch was going out of the back of my legs. We’d had eight or 10 inches of snow earlier, and then a warm spell that softened it, followed by three or four cold nights that left a hard crust. The new snow that had come the night before lay over the crust a couple of inches deep, and the fox was traveling as light as thistledown. I wasn’t doing quite that well. The crust supported me for two or three steps, but then I’d break through for two or three. It was the hardest walking I could remember.

The fox ran for a quarter mile after he left the cattails. Then he got over the worst of his scare and slowed to a trot once more. He left the swamp, went through an abandoned field grown up with weeds and scattered brush, and then cut across a woodlot. I found two or three places where he had stopped near the top of a rise to look back nervously while trampling the new snow. Once he even sat down while watching his track to see if I was following, but I hadn’t seen him, and I didn’t think he had seen me.

I was more than a mile from where I’d taken the track by then, and I was getting mighty tired, but the fox acted as fresh as a daisy. I was beginning to wonder whether I was going to catch up with him after all.

We had come almost due north, but at this point he swung off to the east, and I decided he was going to do what just about every game animal from a cottontail to a deer does if they’re driven — make a big circle and head back toward the start.

That was a good guess. I followed him east for a while, and then he went down into another swamp. When he left it, he was headed south in the general direction of the haystack.

His track led into a big cornfield where the fodder had been left standing after the ears were picked. If I jumped him there, I’d have no chance for a shot, but he went through without stopping. I put him up for the second time at the far side of that field out of a clump of sweet clover along the fence. He had made two beds there, only a few feet apart, as though he had been too uneasy to stay in one place for long. When I put my hand in the bed from which his track led away, it was still warm.

Just as before, I had been too late to catch a glimpse of him.

The rest of the hunt was plain hard work and very little excitement. Long before it was over, I told myself that I had been wise to keep out of this business up to then.

The fox continued to travel generally south, trotting most of the time, but now and then breaking into a run for a short distance or stopping on high ground to look back. I plodded along, hating to give up, but knowing that unless I was lucky very soon, I’d have no choice. The afternoon was about gone, and my legs ached.

Three hours, five or six miles, and a couple of quarts of sweat after I had left the haystack, the track led me down into a strip of open marsh. Something told me the fox would stop again in that place, and he did, but it didn’t do me any good. I was halfway across the marsh when I saw him leave the far side, following a brushy fence row up a hill and running like a puff of red smoke. He had seen or heard me or both, and that was the end of the hunt. The sun was down, and it would be pitch dark before I could hope to overtake him again. I was only half a mile from Clarence’s place and from my car, and I’d had enough. I’d give up and go home, eat supper, and try to rub the ache out of my sore legs.

Then something unexpected happened. Clarence had an old 12 gauge double-barreled shotgun with hammers, vintage of before 1900. From the brushy fence row, just over the hill beyond my sight, came the thunder of that old blunderbuss.

I had to find out what the results were, so I slogged wearily the rest of the way through the marsh and up the hill. Clarence was nowhere in sight, but the tracks told the story. The fox had turned down into a ravine, a place that I suppose he had used in his travels a hundred times before. About the time he reached the bottom of it, my old uncle, waiting in an open clump of trees up by the fence, had shot him. I never asked him, but I’d bet a brand-new dollar bill against a stale doughnut that he had killed at least a dozen foxes in that same spot.

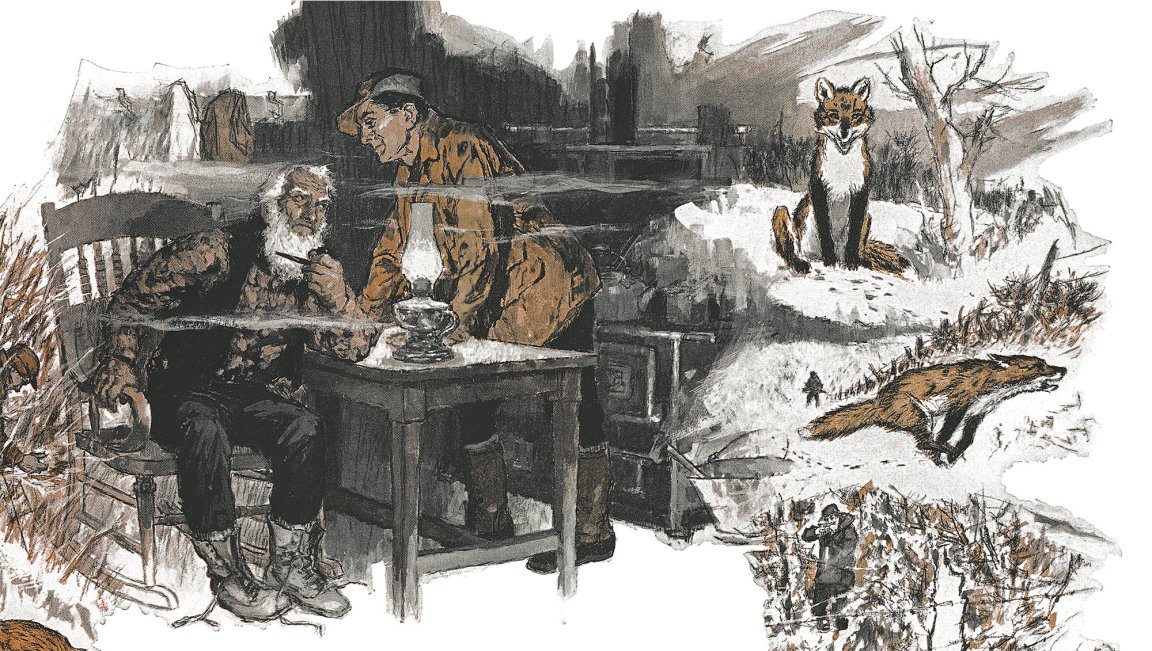

The tracks also showed that Clarence had then started for home, lugging his prize. I legged it for his house, half amused and half provoked. I had been taken, and I knew Clarence well enough to be sure it was no accident. It was getting dark when I arrived. He was sitting in the kitchen, a picture of age and innocence. There was a fire crackling in the stove and an old oil lamp was lighted on the table. The air was blue with tobacco smoke that would have cut the scale off the inside of a chimney flue.

“Did you get him?” he asked with bright-eyed eagerness by way of greeting.

“No, but I’m sure who did,” I retorted.

“Somebody else get him?”

I blew up. “Listen, you old reprobate,” I shouted, “don’t you try to kid me! I walked that damn track all the way to the end, and I know what happened. I know you planned the whole thing exactly that way too.”

I saw a grin crinkle his face behind the grizzled beard.

“Some places they use dogs to drive ’em around,” he said mildly, “but I’d ruther have a man walk the track.”

“If you can find one who’s fool enough to do it for you,” I grumbled. “You had a dog today, only he weighed 150 pounds.”

The grin widened, and the crinkles at the corners of the old eyes grew deeper. “Well, you had a good hunt, didn’t you?” he asked.

I had to agree, and the more I thought about the whole thing, the more I saw the amusing side of it. By the time we had put away a glass of cider apiece, my resentment was gone.

Read Next: Old-School Advice for Still-Hunting Whitetail Deer

“Come out any time there’s a fresh snow,” he invited me when I left. “We can always find a fox track.”

I never took him up on the invitation, but when I think of him now that’s how I like to remember him — 80 years old, lame, there in the old house by himself, a grin cracking his face under the beard and his eyes dancing with devilment for two reasons. He had put something over on a man less than a third his age, and he had killed a fox.