We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

Despite what the internet might lead you to believe, the 6.5 Creedmoor did not start a movement to hunt big game with smaller-caliber cartridges. In reality, folks have been putting big animals down for over a hundred years with cartridges that would have social media commenters’ thumbs worked into a frenzy. They did it without a second thought, maybe because nobody ever told them they couldn’t.

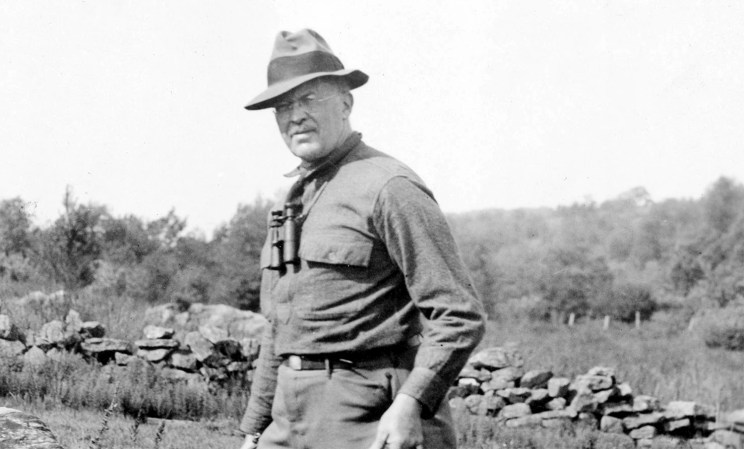

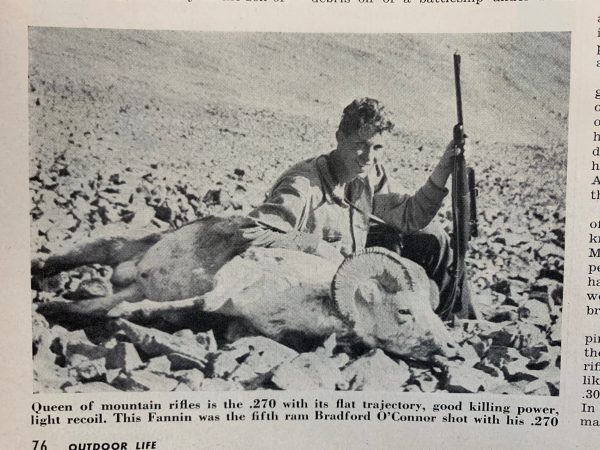

Both Col. Townsend Whelen and Jack O’Connor had an affinity for mild-recoiling, accurate cartridges like the .250 Savage, .257 Roberts, and the .270 Winchester. As former Outdoor Life contributor Jim Rearden wrote, legendary Alaskan hunter Frank Glaser started out with a .250 Savage, and later decided on the .220 Swift to be his favorite cartridge for taking hoofed game.

What Does More Power Get You?

It’s easy to get sucked into the mindset of “bigger is better.” After all, more powerful cartridges typically do offer more devastating performance, and somewhat more forgiveness of error on shot angles. But caliber selection is a personal choice each hunter must make. The problem is that today there are plenty of blowhards who will question whether you even belong in the woods if your rifle is not as big as theirs—regardless of whether they truly understand the advantages or disadvantages of choosing a high-caliber piece of artillery.

Recoil

Sure, more power is more power, but being able to shoot your rifle accurately and with confidence trumps all else. What a high-test cartridge does bring you is more recoil, and a cannon does you no good if you’re scared to pull the trigger. No one would admit to being scared of their rifle, but I’ve seen more than a few grown men with such a bad flinch they couldn’t keep bullets on a paper plate at 100 yards.

Most large-caliber proponents confuse the ability to fire a rifle without crumpling to the ground and the very real affects that heavy recoil has on every shooter. Former shooting editor Jim Carmichel detailed these effects, as did Jack O’Connor. It’s for good reason that high-volume shooters almost always choose cartridges that are more manageable than the speed-demon magnums.

Terminal Performance

Perhaps our expectations of what happens after the shot dictate the direction we choose to go in cartridge selection. If we expect an animal to drop as if hit by lightning, then chasingrpower would be the natural direction. Intuitively, we’d think that the bigger the cartridge, the more quickly it will kill game, but it’s not always that simple.

When selecting a cartridge, you need one that is capable of adequate penetration, and a projectile that will offer sufficient terminal performance at the distance you’re shooting at your chosen game. A species like cape buffalo will certainly require a heavier-hitting cartridge than what you’d need for elk or moose, and more powerful cartridges do offer some terminal benefits. But don’t forget that you cannot out-caliber poor marksmanship. The fantastic performance of a lightning-in-a-bottle cartridge won’t do you any good if you can’t hit what you’re aiming at.

Simple Facts

The fact is, if you punch a quality bullet through the lungs of the toughest bull elk, moose, bear, or caribou, he’s going to die—quickly. A bull moose shot through the lungs with a .25-06 or .270 might not crumple on impact, but he’s not going very far. And moose don’t topple over quickly anyway. In fact, an instant drop is more often the exception. The most dramatic pile-up I’ve ever seen on a moose was at the receiving end of a 150-grain Hornady inter-lock out of my .30-06 at 350 yards—while the last bull I shot showed no reaction when hit twice with a .300 H&H from 100 yards (before falling on his nose).

An Alaska-Yukon moose is a behemoth of a critter that supposedly demands cartridges starting in the .33’s. In reality, more moose have probably been taken with .222’s, .30-30’s, and .243’s in Alaska than any other cartridges. In Canada, the .303 is likely king, which is hardly a powerhouse. The .223 Remington is currently a dominant cartridge in the bush of Alaska, and it has proven to be plenty adequate for caribou when used with well-constructed bullets. And although the .223 would be considered light for moose by anyone’s standards, it still takes quite a few moose in the bush every year as well.

What About Bears?

Bears, especially grizzly bears, are another area for cartridge contention. For guiding purposes, or as a backup gun, it’s not a bad idea to tote something in the .338 to .416 range. But for hunting purposes, it’s simply not necessary. Bears will generally not be anchored in place with a single shot, no matter the caliber. You’ll hear stories of shooting bears in the shoulders to “break them down,” but I know of a few instances where bears were never recovered because of this method. Shoot them cleanly through both lungs and their fate is sealed, usually very quickly. For black bears, a .243 with a good bonded or monolithic bullet is absolutely deadly. This season, my son took his first black bear with the pipsqueak .350 Legend. The bear ran about 10 yards and fell over dead.

Grizzlies do garner a reputation of being a little tougher to kill, but that seems to have much more to do with the bear being aware of the hunter’s presence. In all the guiding and hunting he has done, my uncle still says the fastest death he ever saw of a grizzly was brought on by a .25-06. I’m convinced that a good first shot is much more critical than caliber. I killed a Boone and Crockett grizzly bear with a 6.5 Creedmoor this season, which was on the ground before the echoes of my first shot even subsided. He only made it seven yards. Previously, I shot an equally large bear with a patched roundball out of a .50-caliber muzzleloader. He ran about 75 yards before expiring. Even on giant coastal brown bears, a good shot trumps a big bullet. I know of several big Kodiak bears that were taken cleanly with a .308, and another recently with a 7mm-08.

The Takeaway

The common theme with many cartridge selections historically is ammo availability. The traveling hunter often has the luxury to bring whatever cartridge he or she wishes to the field, but in more remote areas, folks have always used what they had available; often that meant standard, mediocre cartridges. They made it work and still do. As caliber selection applies to us today, this shouldn’t be interpreted as license to try and outdo each other with the smallest cartridge possible.

Read Next: The .270 Winchester Was Your Grandpa’s 6.5 Creedmoor

My point is that a cartridge’s adequacy rests much more in a good-shooting rifle and what’s between the ears of the person pulling the trigger than in some curmudgeon’s ballistics charts. If you’re one of the folks who just needs one good hunting rifle, pick an accurate gun that you’re comfortable shooting and buy good ammunition to shoot through it. If your disdain for popular culture excludes you from owning a 6.5 Creedmoor, pick up a .25-06 and maybe you’ll start your own cartridge movement. Either way, the animals won’t notice.