We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

If there was ever a person whose writing and wisdom embodied Outdoor Life, it was Jack O’Connor. His words were printed on the pages of nearly every issue of the magazine for 38 years. O’Connor’s stories and knowledge are still revered, and you’ll even see O’Connor referenced on social media threads. This is usually in speculation about what his opinions would be on contemporary rifles, cartridges, and hunting practices. To me, he’s one of those stalwart figures to whom every outdoor writer is compared, and none can ever measure up to.

But here’s a question: When’s the last time you actually read a Jack O’Connor piece? If you want to benefit from his knowledge and reference his legend, you’ve got to carefully read the words he put on the page.

His hunting stories are iconic, but his meticulously detailed work in the “Shooting” and “Arms and Ammunition” sections of Outdoor Life provided an incredible amount of instruction to the reader. Reading them today might change some of your perceptions about both O’Connor and the world of hunting and shooting. Much of his advice is just as applicable today as it was 60 years ago, and frankly, some people still need to hear it. It’s easy to remember our hunting and shooting past as the good old days. But when you read O’Connor now, you’ll see the past isn’t all that different from the present.

Evergreen Advice

Jack O’Connor was an expert gunner, and few will ever duplicate the volume and diversity of his experience. In other words, he had plenty of first-hand experience from which to base his shooting tips and advice. Sure, some of the technology has changed since O’Connor’s day, but even the best technology is useless without the proper shooting fundamentals. Here are a few tips that O’Connor wrote decades ago that are equally relevant today.

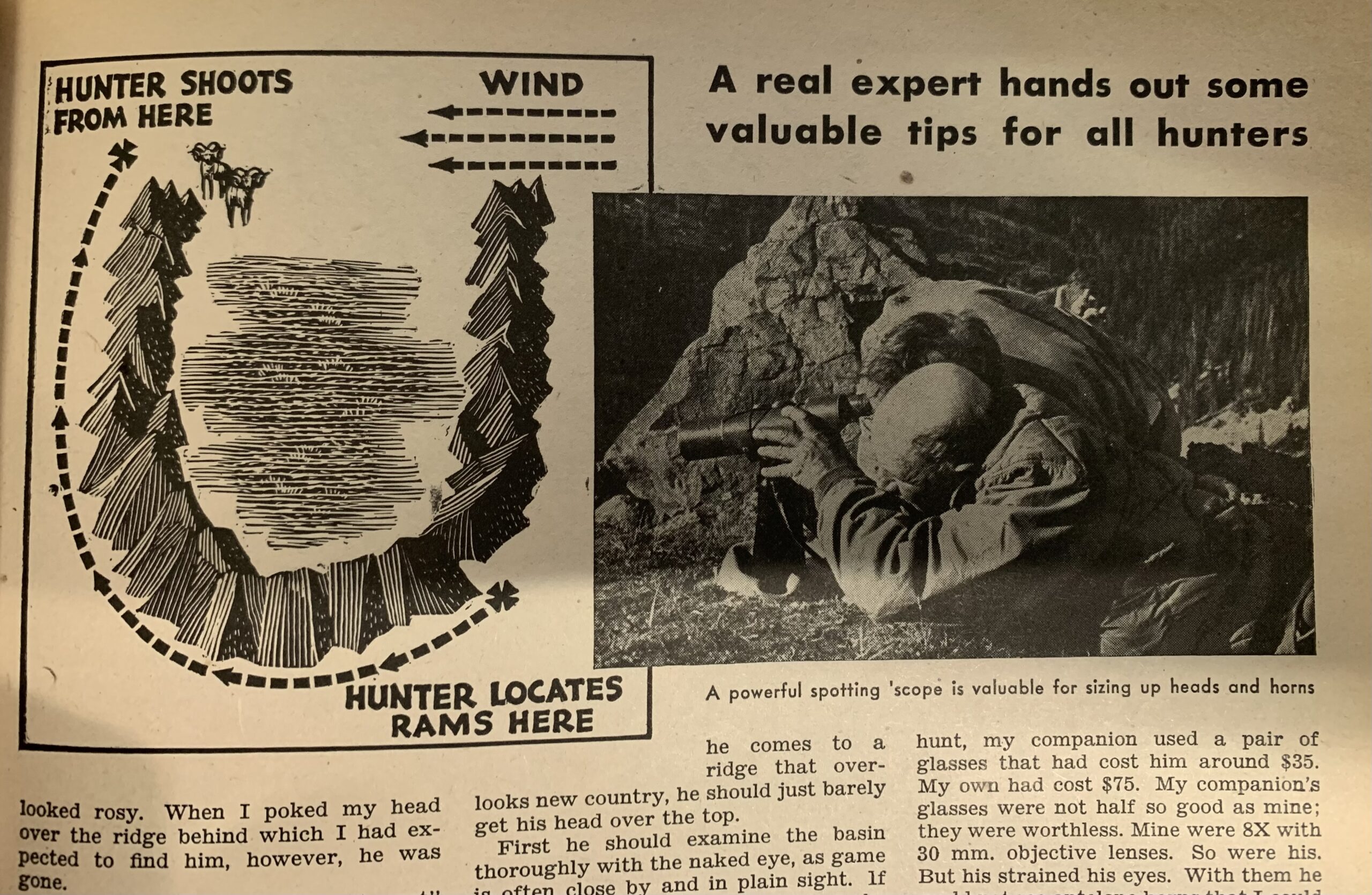

The Art of Stalking Big Game, July 1946

Stalking an animal is one of the most important and underestimated skills in modern hunting. Many of today’s hunters could benefit from a few pointers here. Some common hunting strategies have changed over the years but the need to stalk into range hasn’t changed much at all. O’Connor writes:

“The stalker will locate game before it sees him by taking it slow and never barging into a canyon or basin before he has looked it over carefully. When he comes to a ridge that overlooks new country, he should just barely get his head over the top. First, he should examine the basin thoroughly with the naked eye, as game is often close by and in plain sight. If that examination yields nothing, he should use binoculars, carefully examining every suspicious-looking object, peering into shadows, watching the places where game might bed. If a slow and thorough examination yields nothing, then he can cross the basin to look into another.”

He continues in detail, describing a theoretical stalk on bedded rams. He then expands into other situations and examines factors like the wind and terrain, emphasizing the importance of seeing the animal before it sees you.

Sight In for Big Game, October 1956

One of the most vivid memories I have from my hunter-education class that I took while in second grade was a lecture on sighting in your rifle, and I took it to heart. In this shooting section article, Jack exercises his typical thoroughness with an anecdote about his pal Tom, whose rifle was sighted in for one type of ammunition, but he was hunting with another. O’Connor followed this with step-by-step instruction that can be easily applied today. He writes:

“Many hunters never fire their weapons at all before going hunting. Others never fire them on paper. So let’s remember these things: A rifle may indeed be sighted in, either by the factory or by a former owner, and yet not be right for you. It may not be sighted in for the distance you want. Most factory rifles are sighted to put a certain bullet to point of aim at 100 yd. In many Western states, where shots at deer run from 200 to 300 yd., a rifle sighted in for 100 yd. will cause a lot of misses. Also, unless the rifle is sighted in for the ammunition you want to use, you may run into the same trouble that Tom did. Some rifles will put anything you feed them into just about the same group to 100 yd. Others are very sensitive to changes in bullet weight, or velocity, or even to the kind of powder or the hardness of the bullet jacket...Anyone with enough mechanical ability to sharpen a pencil or to lace his shoes can sight in a rifle quickly and easily.”

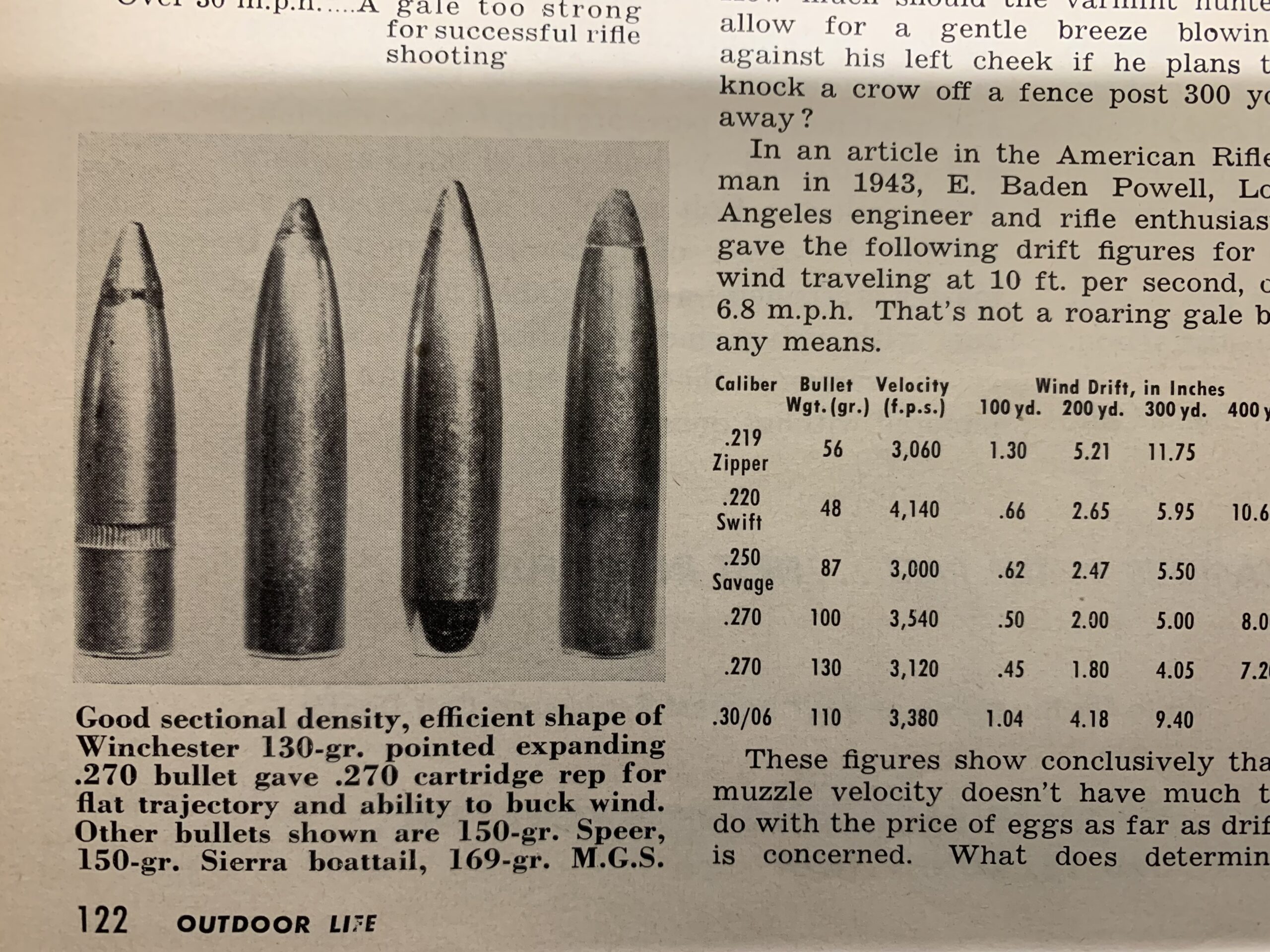

Bullets In the Breeze, March 1957

Although bullet technology has improved in the past 60 years, the wind still blows, and dealing with it is a fact of life for long-range shooters. Here, O’Connor covers how wind impacts a bullet’s flight, and he also gets into specifics about how it affects common loads of the day.

“The 200-yd. small-bore shooter or the 600- or 1000-yd. competitor with the .30 caliber rifle may be able to hold like a rock and squeeze gently, but unless he can read the wind he is sunk. The big-game hunter in brush and forest where ranges are short needn’t bother his pretty head about wind effect, but once he goes out into the wide-open spaces the breeze begins to bother him. In that wonderful antelope state of Wyoming, for instance, the wind is almost always blowing—at least when I am there. Since pronghorns are as rule shot at fairly long range, it behooves the hunter to do a little wind doping before he touches old Betsy off. If he doesn’t, he’s likely to wonder how come he hit his antelope in the south end when he held on the north end…”

Since this was written, the availability and precision of wind meters and ballistic apps have made making windage adjustments easier. But understanding reading the wind and understanding how it impacts your specific load are still timeless skills that technology haven’t replaced.

Decades-Old Debates

O’Connor also wrote about a whole bunch of topics that we as a hunting and shooting community are still arguing about today. Yes, some of the details change, but you might be surprised (or maybe unsurprised) by the topics that were controversial back then, and still are today.

Long-Range Shooting

Shooting animals at a far (but undefined) distance is taboo for many in the hunting community and it was back then, too. Critics will say that long-range rifles, optics, and high-B.C. bullets have bastardized hunting from what it once was: a pure sport of stalking skill. We think this conversation is a result of our new technology, but hunters have been striving to shoot long distances since O’Connor’s day—and well before it. In the January 1950 issue of Outdoor Life, O’Connor’s story Long Shots in the Cascades detailed a British Columbia hunt in the company of Roy Weatherby, where the party shot their mountain goats and bucks between 300 and 600 yards.

“How far away do you think it is?” he asked.

“About 500 yards,” I said.

The .270 cracked and the buck fell on its nose. I watched through the binoculars as it kicked a few times and then lay still. If you want to get an inferiority complex, just hunt with that guy Niles when he’s hot!

Later in the “Arms and Ammunition” section of the same issue, O’Connor writes on varmint hunting:

“Now and then I get a letter from an indignant citizen who is aware of this feverish interest in long-range varmint shooting, and who heartily disapproves of it. What he gets a kick out of, he says, is sneaking up on unsuspecting chucks and popping them in the head with a .22 at 30 or 40 yd. He can see no point at all in staying over there in the next country and knocking off a chuck a quarter of a mile away. He has his point, possibly; but actually he is not a varmint shot at all. He’s a stalker, and he isn’t really interested in precision shooting but in skillful stalking. One angry chap wrote me that shooting a chuck at a quarter of a mile proved nothing. I’ll say that shooting a chuck at 30 yd. proves even less.”

Perhaps Jack’s perspectives changed over the years, but I get the impression that he had a very balanced and informed opinion on such matters. In the shooting section of the October 1964 issue, he gives tips for shooting at longer ranges, but also adds a healthy a dose of reality by saying that many people greatly exaggerate the ranges at which they shoot. He also makes the case for shooting at reasonable distances.

“I know a bit about sheep hunting, and if I were a sheep guide and a dude wanted to shoot up a bunch of rams at 600 yd. I’d kick him humpbacked. …When should a hunter take a crack at an animal at long range? Only, I am convinced, when he is 95 percent certain that he can kill the animal before it gets out of sight. Whether he should shoot or not depends on how far the animal is away, how quickly it can get out of sight, how well the hunter can shoot, and how steady a position he can assume.”

Medium Calibers

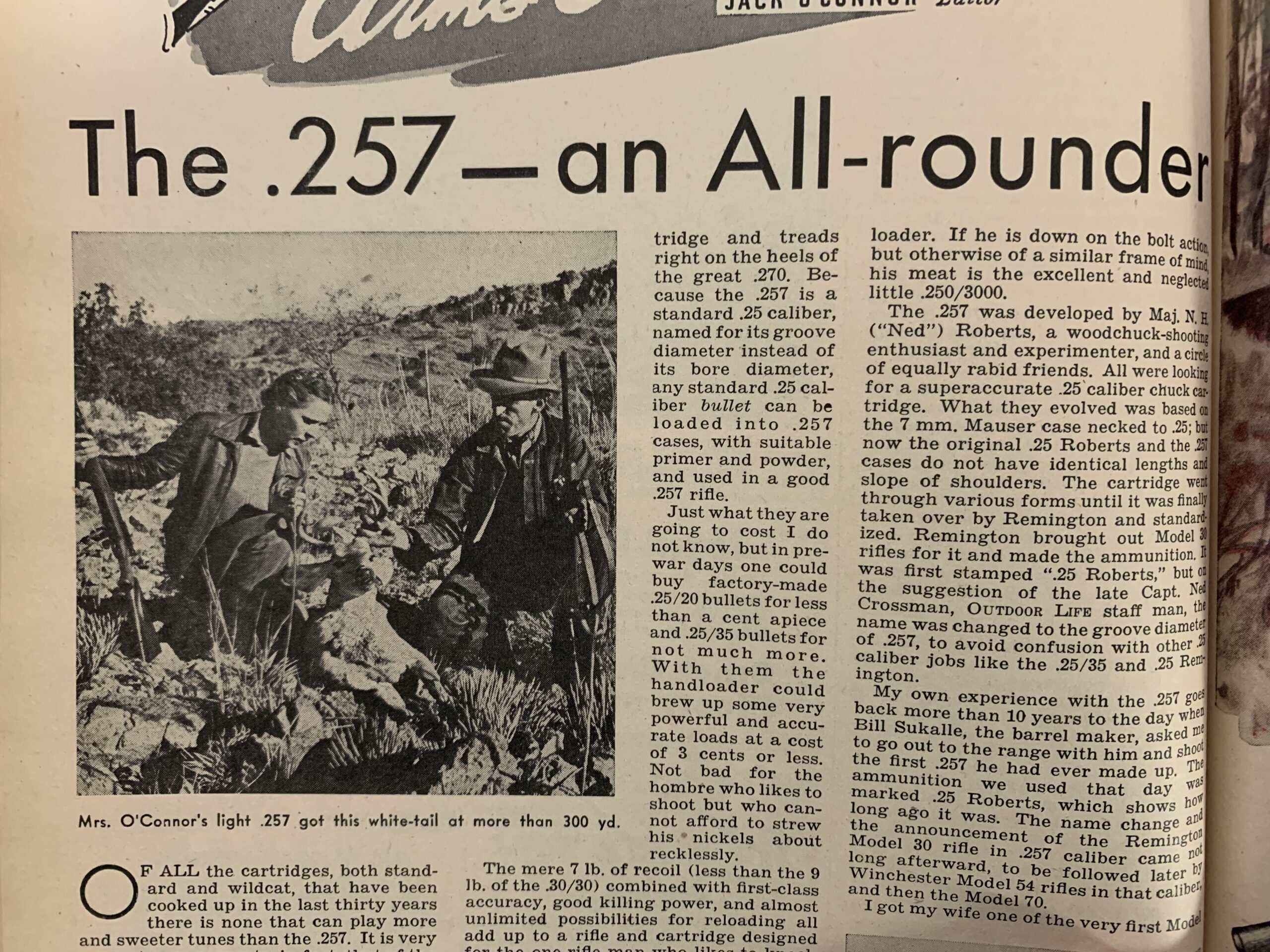

Another divisive topic is the so-called medium caliber cartridges. Just look at the popularity of, and hostility toward, the 6.5 Creedmoor. It seems as if you must either love or hate the Creed. The new 6.8 Western cartridge has its own set of fans and detractors as well. Whether it stands the test of time is yet to be determined, but I think that O’Connor would have been enthusiastic to evaluate it at the very least. Jack will forever be associated with the .270 Winchester, and he certainly had an affinity for it. If you read much of his work, however, you may be surprised or even disappointed at the realization that he was a self-described cartridge geek and wrote enthusiastically about scores of cartridges that were being developed over the decades. He even had an affinity for lower-recoil, medium-sized rifle chamberings that were easier to shoot. He would rattle off ballistic coefficients, sectional densities, velocities, and trajectories. He writes about the .257 Roberts in The .257—An All-Rounder in the April 1946 issue of OL, speaking fondly of its accuracy and mild recoil, while being realistic about its applications.

“Of all the cartridges, both standard and wildcat, that have been cooked up in the last thirty years there is none that can play more and sweeter tunes than the .257. It is very accurate-so accurate, in fact, that of the dozen or more rifles of that caliber which I have got to know well I have never seen one that wouldn’t shoot into 1 ½ in. at 100 yd. Most will do much better, and groups under 1 in. are common. Recoil is so light that a woman or boy can shoot one without developing a flinch—and so can the office-chained hombre who has to do most of his shooting in the pages of his favorite sporting journal.”

In a similar piece, printed a few years later in December 1953 called The All-Round .25 Rifle, O’Connor details several 25-caliber cartridges from the .25/35 and .250/3000 to the .25/06 and .257 Weatherby. He sticks with his opinion that a .270 or .30-06 is ideal for large big game, but he’s a fan of the fast and mild-kicking .25’s.

“As far as larger game goes, Dr. E.G. Braddock of Lewiston, Idaho, has hunted elk for years with the .257 and has killed more than a dozen with no lost animals. And the late Jean Jacquot used the .250/3000 on Yukon moose and grizzlies for the last 30 years of his life. I wouldn’t pick a .250 as an ideal grizzly rifle, but one of these days, just as an experiment, I’d like to tie into a nice juicy grizzly above timberline with a .257 loaded with a 117, 120, or 125-gr. Bullet at around 2,900-2,950 (fps).

The good .25’s then, are worthy of respect and investigation. They are accurate; their recoil is light; and their report is not bad, even when they use a lot of powder to drive their bullets at high velocities. As all-round rifles to be used on varmints and the smaller big game they are tops.”

If you learn anything from reading O’Connor’s more technical writings, you’ll learn his appreciation for innovation and development. He had his darling cartridges, but he also had a thorough knowledge of both rifles and ammunition, and a very practical outlook. Were he alive and writing today, I don’t think he would forsake the cartridges he favored, but I am confident that he wouldn’t ignore new cartridges or dismiss them as gun industry gimmicks. For decades, he used and evaluated just about every new cartridge and rifle that hit the market.

The only downside of looking back on hunting’s past as the “good old days” is if it prevents you from looking forward. I’m not sure what Jack O’Connor would think about the world today, but I bet he’d be pretty damn happy about being able to carry a supremely accurate, 6-pound rifle into the sheep hills.