We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

Whenever I’ve been out hunting or shooting and have experienced a flat-out miss for no good reason, I’ve been known to say, “But I’d sell you that sight picture”—meaning that the crosshairs were exactly where I wanted them when the shot broke.

This happened on an antelope hunt in Wyoming. I was hunting with a group that included my wife and some of our friends. We spotted a herd of goats and executed a stalk. After crawling for 100 yards through sagebrush and a foot of snow that had fallen the night before, we got into shooting position on a knoll about 150 yards from the herd. I had a doe/fawn tag, and after quietly watching the animals, I picked a doe that did not have any yearlings still with her. I steadied my rifle, a recently built .358 Winchester using 225-grain Sierra Spitzer boattails, for a shot off my shooting sticks.

An Epic Miss

At the crack of the shot, the last thing I saw in the scope was perfect crosshair alignment, and I felt the rifle tracking straight back toward me. I expected excitement and high fives, but instead my buddy said, “I can’t believe you missed that doe by that much!” He watched the bullet impact way over her back. Now, I’m not the best shot in the world, but I know when I have a good sight picture and execute proper follow-through. Immediately my mind started churning, and the best I could come up with was the possibility that I had snow in the barrel. Remember the crawl to get into shooting position?

Upon returning to work (as chief ballistician for Sierra Bullets), I thought up a test to verify or debunk the theory that snow or water had gotten into the muzzle of my rifle and caused a wild shot. During my hunt, I did not have anything covering the muzzle, and, as you know, since a .35-caliber bore diameter is fairly large, it could easily have gotten contaminated.

The Test

I loaded nine rounds of .308 Winchester ammunition with 165-grain SBT bullets and approximately 38 grains of Accurate 2495, a combination that I know shoots well. [Editor’s note: Although this load was safe in the rifle used in this test, it may not be safe in your specific firearm.] I then shot them through a fouled .308 Winchester barreled action in one of our return-to-battery machine rests at 200 yards.

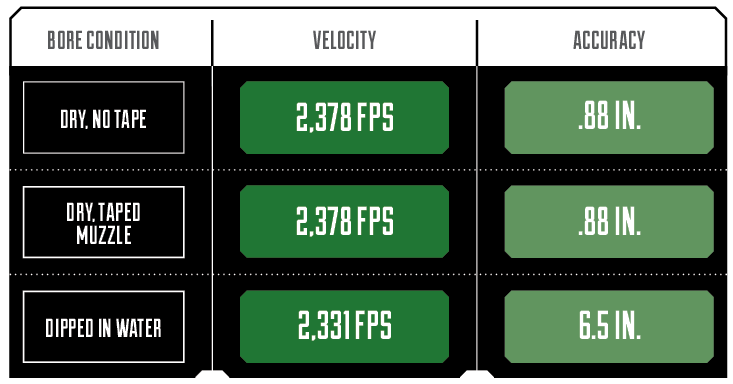

I fired three shots and documented the velocity at 2,378 fps. I then fired three more shots, but before each shot I placed a piece of electrician’s tape over the muzzle, which would keep water, snow, and debris out of the barrel during a hunt. There was no change in either accuracy or velocity with the electrician’s tape in place.

Next, my right-hand-man in all things bullet-related, Tony Kelley, dipped the muzzle of the test rifle into a bucket of water before each of the next three shots.

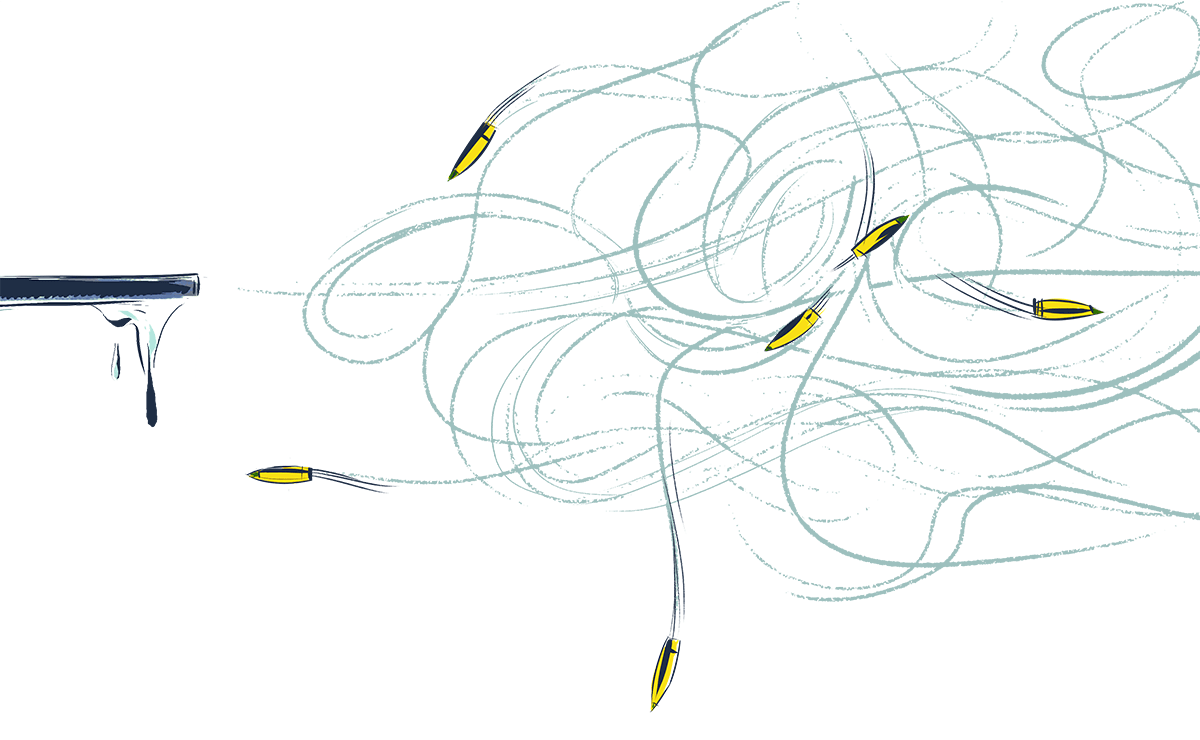

Shooting with the last 8 inches or so of the bore wet reduced the velocity of this load by 47 fps. As you can see from the results below, you don’t want any water in your barrel if you intend to hit what you’re aiming at. I believe I found the reason that the doe escaped my efforts to transform her into table fare.

Luckily for me, an hour after my miss I got another chance at an antelope and made a good shot at approximately double the distance of the first attempt. That bullet hit precisely as intended, and I was able to fill my tag and my freezer. I’m betting that the barrel interior was wet the first time and dry the second. I have often heard the saying, “Keep your powder dry.” And from my experience and this test, one could add “and your barrel.”

.308 Win. shooting a 165-gr. SBT bullet @ 200 yards, 3-shot groups