Invasive species are a dime-a-dozen these days, but rats in Alaska aren’t exactly hitting front pages. Despite being one of the most common species ever spread throughout the world, rats aren’t an animal that’s widely associated with Alaska. Alaska’s Aleutian Islands, however, have had a rat problem that dates back to the founding of the United States itself.

In approximately 1780, a Japanese ship wrecked off the coast of Hawadax Island. Stowaway rats made it ashore and quickly established themselves in a rodent’s paradise of nesting birds and a predator-free ecosystem. Eventually Hawadax took on the name “Rat Island.” These rats in Alaska rapidly gained a foothold as they played hell with the ecosystem. They spread to other islands during World War II as Navy ships moved throughout the Aleutians. Today, rats in Alaska are still having a devastating impact on shore birds and other native wildlife on these islands.

“The rats are like an oil spill that keeps on spilling year after year,” said Steve Delehanty, the refuge manager for the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge in a quote from a KTOO news article talking about ongoing rat control efforts. “We would never allow an oil spill to go on for decades or centuries, nor should we allow rats to be a forever-presence on these islands.”

In 2008, a team of scientists traveled to “Rat Island” and dropped poison pellets across the island via helicopter. They were successful in exterminating the rats on the island, but some other animals—including bald eagles—fell victim too, when they ate poisoned rats. Over a decade later, however, the island remains rat free. Scores of nesting birds and flourishing grasses have returned, too. The island’s original Aleut name, Hawadax, was even restored. (A recent article in Popular Science details some of the detrimental effects the rats had on the landscape, and how removal helped reverse those issues.)

The general consensus among wildlife managers that there should be no future for rats in Alaska. According to KTOO, efforts to exterminate rats from other Aleutian islands are underway, but with a more careful approach. Other islands are being treated with non-toxic test pellets to track the potential effects of future poison pellets on the marine and terrestrial ecosystem, so managers can minimize collateral damage. Eventually, however, the plan is to kill every last rat.

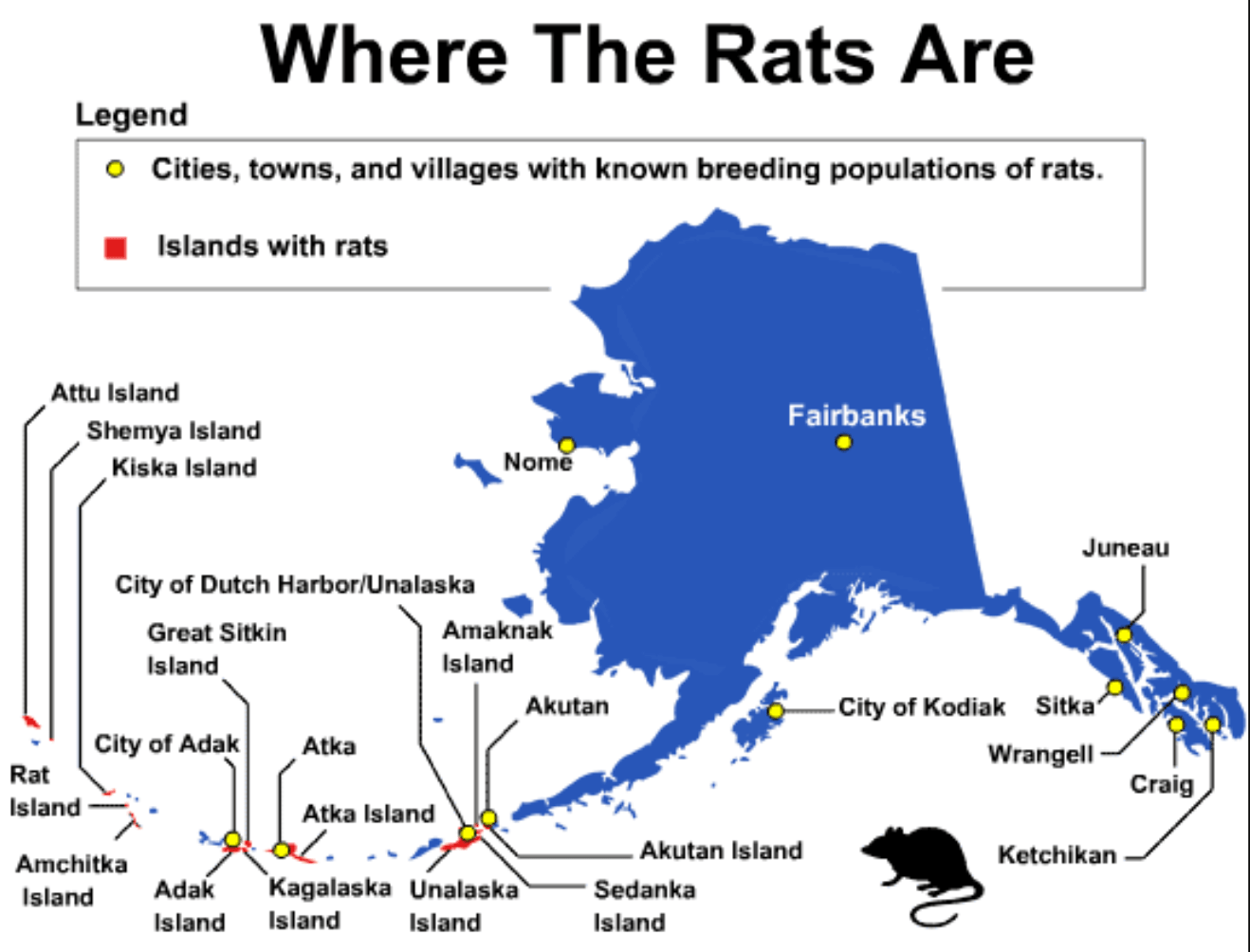

As of 2020, Anchorage was likely the largest rat-free port in the world, according to the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. It’s even illegal to own a pet rat in Alaska; only laboratory rats are permitted in the state. ADFG even lists Fairbanks, deep in the interior of the state, as having a population of rats. (Despite my years of crawling through and working in hot, steamy utility tunnels in the Fairbanks area, I’ve yet to see a rat. Cockroaches, however, are another story.)

The Alaska Department of Fish and Game points out that despite strong management efforts, a small surviving population of rats in Alaska can hang on and then explode if conditions are right. “Surviving can become thriving with a few good breaks for the rats,” said Tammy Davis, who coordinates Fish and Game’s Invasive Species Program.

“They may harbor at low levels, and then reproduce quickly if conditions or circumstances work in their favor,” she said. That happened in 2017 in Ouzinkie, a small community 20 miles north of Kodiak. “Weather might have been controlling the population, then we had a couple warm winters and survival was good.”

Biologists are documenting the movements of rats as best they can, and rely on tips (and when they can get them, dead rats) from residents.