As game and fish agencies across the country struggle to figure out what the future of wildlife management holds, comparing conservation vs preservation is more relevant than ever. The two words and their respective schools of thought toward natural resource management overlap way more than they differ. But that detail gets overlooked in heated debates about everything from realistic land use to protecting endangered species. How do we approach trophy hunting in North America? Should grizzly bears finally be delisted? How many mule deer tags should be made available to hunters after a season of major winterkill? How do we protect wildlife in extreme droughts and wildfires?

The answers to all these questions must balance conservation with preservation to determine whether sustainable use and harvest is appropriate and, if so, how much to allow for. Let’s clear up some of the confusion around conservation vs preservation.

Conservation vs Preservation: The Upshot

In the simplest terms, preservation-minded folks advocate for leaving wildlife and wildlands untouched while more conservation-minded folks advocate for the sustainable use of renewable resources. For instance, preservationists generally believe wild forests shouldn’t be logged for timber. Conservationists believe logging can be done responsibly, both to obtain lumber (a resource that will eventually grow back) and to improve forest health. But ultimately, conservation and preservation both work toward identical goals: to safeguard natural resources for both the future success of the species and the enjoyment of the public.

Because the goals of conservation and preservation are so similar, their definitions are similar, too:

- Conservation is “a careful preservation and protection of something, especially planned management of a natural resource to prevent exploitation, destruction, or neglect.”

- Preservation is “the activity or process of keeping something valued alive, intact, or free from damage or decay.”

To understand the differences between modern conservation and preservation, we need to look deeper.

Conservation vs Preservation at Work

There are countless non-profit organizations working to support conservation efforts, preservation efforts, and a combination of the two. While it’s tough to classify many of these groups as wholly conservationist or wholly preservationist, here’s a list of each based on what they most closely represent in a wildlife and wildlands context.

Popular Conservation Organizations

These groups tend to target hunters, anglers, habitat managers, public-land users, and general wildlife enthusiasts. They can have some overlap with memberships from some preservation organizations, but supporting lawful hunting and fishing are generally part of the organization’s focus.

- Backcountry Hunters and Anglers

- Boone and Crockett Club

- Ducks Unlimited

- National Wildlife Federation

- Pheasants Forever/Quail Forever

- The Nature Conservancy

- Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership

- Trout Unlimited

Popular Preservation Organizations

These groups tend to target birders, backpackers, environmentalists, and general wildlife enthusiasts, as well. While most of these organizations don’t denounce lawful, regulated hunting and some recognize the role that hunting plays in wildlife management, they might also involve animal welfare activism and anti-hunting perspectives.

- Center for Biological Diversity

- Defenders of Wildlife

- National Audubon Society

- Natural Resources Defense Council

- Sierra Club

- Wildlife Conservation Society

- Wildlife For All

How Does Conservation Work?

Conservation relies on the sustainable, regulated use of a resource as a way to protect it. This might seem like a contradiction to those unfamiliar with the many global successes of this model. Why kill animals to help safeguard a species? Why cut down trees to protect a forest?

Conservation-minded folks acknowledge that our human reliance on natural resources—food, water, land, minerals, and other materials—is too great. They simply cannot be preserved in their entirety. Still, to enjoy those resources indefinitely, we must take care of them.

Conservation in Wildlife Management: The North American Model

As European colonizers expanded westward in the 18th through early 20th centuries, rampant market hunting to support burgeoning demand for feathers, furs, hides, and meat almost wiped out species that have returned in robust numbers across North America—deer, elk, waterfowl, upland birds, and furbearers. That’s because modern hunters, who have a vested interest in healthy wild game populations, have helped restore and conserve these species.

Some species, like wild, free-roaming bison, essentially met their demise. The late conservation expert Jim Posewitz writes of this tainted moment in history in his book, Beyond Fair Chase: The Ethic and Tradition of Hunting;

“Since [wild] animals were owned by no one in particular, people were free to kill and sell them. Regulations and limits didn’t seem necessary because wildlife was so abundant. As a result, enormous numbers were killed for commercial purposes. Their hides, meat, feathers, and other parts became resources in an unregulated marketplace. It was wildlife’s darkest hour, and national tragedies occurred.”

It became clear that, as long as these unregulated hunting and trapping practices continued without moderation, there would be no wildlife left to hunt and trap. So, lawmakers started instituting responsible safeguards to suppress unlimited shooting of game and separate the practice from immediate financial gain. Regulators accomplished these modern conservation wins by setting hunting seasons that limited what species and how much hunters could harvest.

Some states on the East Coast had already established deer seasons as early as the late 17th century. Massachusetts closed January through July to deer hunting in 1694; the penalty for a first violation was 40 shillings, or roughly $460 in modern U.S. dollars. New York instituted a closed deer season from January to July in 1788. More states established closed deer seasons throughout the 19th century, before any federal action was taken to address market hunting concerns.

Here are some key pieces of conservation legislation that are essential to our modern approach to wildlife management in the U.S.:

- The Lacey Act of 1900, which was the first federal wildlife law and prohibited the interstate transport of poached birds and game to help curb market hunting

- The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, which brought migratory birds under federal management and protected them from overharvest

- The Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp Act, which required hunters, some of whom at one point got paid to haul punt guns around and shoot huge swarms of birds, to start paying for a federal Duck Stamp to hunt birds

- The Pittman-Robertson and Dingell-Johnson acts, which surfaced in 1937 and 1950 respectively and committed revenue from all hunting and fishing licenses and excise taxes on guns, ammunition, tackle, gear, and even boat gas to funding state wildlife agency activities, namely the acquisition of wildlife habitat

These laws and regulations probably seemed like absolute nonsense to some hunters and anglers at the time. But we have them to thank for our current wildlife populations.

Now, it’s illegal to sell hunter-harvested meat from native, free-ranging wildlife in the United States, and the sale or purchase of hides, pelts, antlers, skulls, and other parts of hunter-harvested animals might be subject to regulations and permitting requirements depending on what state you live in. In order to harvest wild animal parts, hunters, trappers, and anglers first need to pay into a sustainable future for these species by buying licenses, permits, and taxed equipment. That revenue goes to state wildlife agencies tasked with managing those species. This pay-to-play standard is the basis of the North American model of wildlife conservation, which is the popular set of principles that honors hunting, fishing, and trapping as a keystone of modern wildlife management in the U.S.

According to the Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, the seven pillars of the North American model include:

- Wildlife resources are conserved and held in trust for all citizens.

- Commerce in dead wildlife is eliminated.

- Wildlife is allocated according to democratic rule of law.

- Wildlife may only be killed for a legitimate, non-frivolous purpose.

- Wildlife is an international resource.

- Every person has an equal opportunity under the law to participate in hunting and fishing.

- Scientific management is the proper means for wildlife conservation.

When state agencies manage wildlife, both game and nongame species, that management takes many forms:

- A game warden busting a poacher

- A state biologist collaring an elk calf as part of a population dynamics study

- An agency’s outreach coordinator and big game manager hosting a public meeting to inform and engage local hunters on the season-setting process

- A state biologist conducting songbird nesting surveys or monitoring monarch butterfly migrations

- An invasive-species specialist using controlled burning to eradicate noxious weeds that choke out and threaten native plants, which native wildlife evolved with and rely on for food

The harmonious relationship that overwhelmingly exists between hunters, anglers, trappers, shooters, boaters, duck-stamp buyers, other wildlife conservationists, and many government agencies has sustained robust wildlife populations nationwide for decades. Ultimately, this model balances the human demand for wild game with the available “supply” of wildlife, to put it in sterile terms. But when the wildlife supply runs low, a much stricter approach is often necessary to protect the resource.

How Does Preservation Work?

At its core, preservation involves strict limits on the human use of, and interaction with, natural resources. The ultimate goal is to protect those resources from imminent danger or destruction. Since preservation is a more hands-off approach to wildlife and land management, it’s often reserved for managing species and landscapes that are in dire straits.

More preservation-minded folks wish to see species and landscapes left alone, free of any intervention. Preservationists are seriously concerned about the footprint our human activity leaves on natural resources and would prefer to see them used as little as possible to meet our needs. The ultimate goal is to leave the natural world to its own devices while we operate as independently of our natural resources as possible for the sake of protecting those resources.

The famous quote “take nothing but photographs, leave nothing but footprints” sums up a preservationist approach to wildlife and land management perfectly. The earliest version of this quote is attributed to Chief Seattle of the Duwamish Tribe, and it has since found a home on signs around national parks and is affiliated with Leave No Trace principles. Whether you are more aligned with a conservationist approach or a preservationist one, outdoorspeople of all creeds should get down with practicing personal responsibility and LNT on our lands and waters. Littering, destroying native vegetation, defacing cultural resources and artifacts, and not following safe campfire protocols range from being very uncool to very illegal.

Preservation in Wildlife Management: The Endangered Species Act

In the 1960s and 70s, Congress passed a series of laws meant to preserve endangered species in the face of growing environmental concerns. The Endangered Species Preservation Act of 1966 was the first, and was accompanied by the inaugural list of endangered species. It comprised 36 bird species, 22 fish species, 14 mammal species, three reptile species, and three amphibian species. The act became the Endangered Species Conservation Act in 1969 and stretched to protect threatened species, or species that were in just slightly better shape than endangered ones. That same year, Nevada became the first state with its own endangered species laws. (Many other states also have their own endangered species lists and respective laws regulating the management of those species.)

Congress passed the Endangered Species Act in 1973 to combine and strengthen prior federal laws protecting at-risk species. Despite the seemingly repetitive nature of these multiple pieces of legislation, preservation from “take” was the focal point of endangered species management.

To condense a complex area of natural resource law, any “take” of a federally endangered species is a federal crime. But “take” has a wide-reaching definition that includes “to harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture or collect.” The inclusion of “harm” also covers “significant habitat modification or degradation.”

In other words, you can’t legally mess with an endangered species. Obviously, killing one on purpose will get you in deep trouble. There can also be consequences for accidentally killing one, or otherwise causing it injury or distress. Endangered species are subject to more preservation practices because, aside from watching a black-footed ferret at a zoo or spotting a grizzly bear at a national park in the Lower 48, there is no real avenue for sustainable “use” of them. Federal wildlife managers are tasked with protecting these species from any sort of human impact, with the exception of hands-on research practices, which must adhere to strict laws.

There’s usually a good reason for this. Most species protected by the ESA are at serious risk of extinction or extirpation (extinction from a specific area or state), and modern society as a whole is mediocre at best when it comes to responsibly coexisting with wildlife.

When Conservation and Preservation Clash

There is obvious room for discord between conservationists and preservationists. These fights especially pop up in discussions about how to manage charismatic species like wolves and grizzly bears. Plenty of conservationists believe enough of each species exist on the landscape that limited hunts should be allowed. These are opportunities that hunters would pay top dollar into their state agencies for. In other words, responsible management of a few individual animals would provide more funding to help support the overall populations of wolves and grizzlies, while also helping manage human-predator conflicts. Many preservationists balk at such an idea, citing concerns about poaching, population dynamics, and other issues that could put an already-fragile species at increased risk.

The Land-Use Debate: Muir vs. Pinchot

People have both conserved and preserved natural resources in North America for tens of thousands of years. But the most current laws modeled after these ancient principles are often traced back to two famous names: Sierra Club founder John Muir and U.S. Forest Service founder Gifford Pinchot.

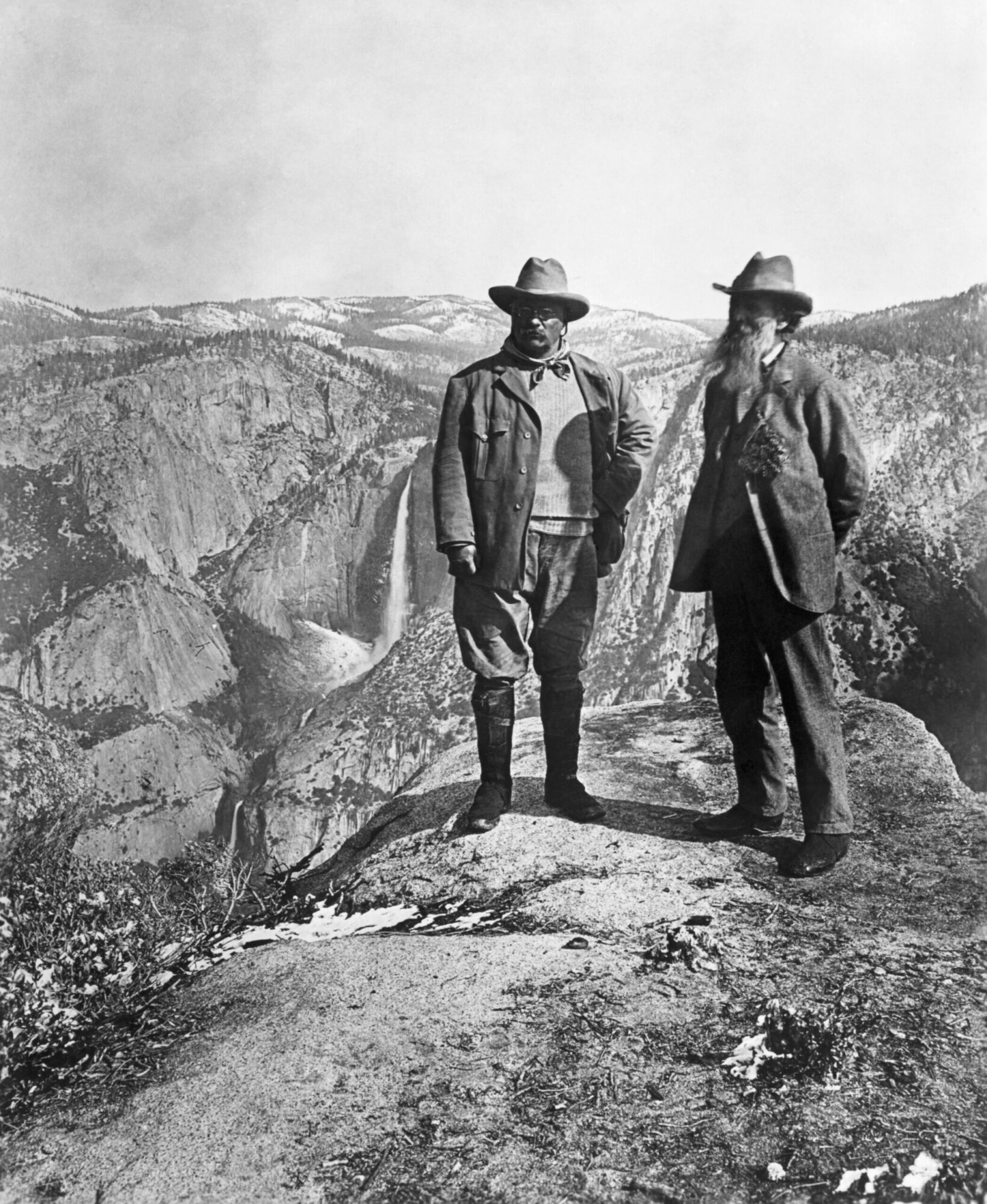

John Muir was a naturalist and writer who cofounded the Sierra Club in his later years. Gifford Pinchot was a forester, the first chief of the USFS, and the founder of the Yale School of Forestry. (He also went on to be a two-term governor of Pennsylvania.) Muir represented a more preservationist approach to land protection while Pinchot took a more conservationist approach. Both men had the ear of president Theodore Roosevelt as he worked to establish his own legacy of protection in the wake of rapid westward expansion, unregulated market hunting of wildlife, and unsustainable logging practices razing much of America’s standing timber.

While today’s approach to politics and resource management would suggest that Muir and Pinchot hated each other, they actually inspired one another. One account from Humanities harkens back to a time when they shared a campfire on the South Rim of the Grand Canyon, staying up long after their companions had returned to the hotel and gone to sleep. As the sun rose, they crept back to the hotel, feeling like “guilty schoolboys” as Pinchot wrote. They were even fishing buddies. (We could all stand to learn a thing or two from their relationship.)

But they also butted heads over issues like construction of the Hetch Hetchy Dam in San Francisco. Pinchot thought it a necessity to meet the city’s water demands, and the very idea broke Muir’s heart. President Woodrow Wilson authorized the plan in 1913; Muir died just over a year later.

Despite the various impasses Pinchot and Muir arrived at throughout their lives, each man’s school of land management complemented the other’s. Now, our heavily regulated national parks—products of Muir’s dream to preserve America’s crown jewels—are mostly surrounded by huge swaths of national forests born from Pinchot’s vision of sustainable use. Most national parks are highly regulated. They require, for instance, entrance fees, backpacking permit applications, packing out human waste, and dogs to stay leashed or in your vehicle. This is the price we pay to continue coexisting with fragile natural features like the geysers of Yellowstone National Park, the rock structures of Arches National Park, and the alpine wildflowers of Glacier National Park. National forests, on the other hand, allow for regulated timber cutting, mineral extraction where permitted, hunting, fishing, foraging, and recreation. These landscapes are often just as beautiful and generally more accessible to the public.

As OL contributor Diana Helmuth points out in her beginner’s guide to backpacking, if you want to see the most shocking natural features on the continent, plan ahead and get a permit to backpack in a national park. If you want the freedom to roam, camp wherever you please, fish, forage, and hunt when legal, hop in your car and go backpack in a national forest or BLM land.

Conservation vs Preservation: FAQs

Based on decades of success, the best method of conservation for wildlife is to establish sustainable, regulated “use” of a species that helps keep that population at a healthy size and generates revenue to invest in the species’s future. This is how we enjoy and conserve our game species in the U.S., like whitetail deer and wild geese.

The best method of preservation in wildlife management is to protect a fragile species from human impact by supporting quality habitat for that species, studying it to better understand its needs in a human-dominated world, and legally prohibiting any harassment, habitat destruction, killing, or other forms of “take” to keep the species’ population from dropping even further. With roughly 500 wild migratory whooping cranes left in the world, the species can’t afford to lose a single individual.

Restoration involves bringing missing or heavily impacted species and ecosystems back to sustainable levels. While conservation and preservation are both proactive approaches with the shared goal of keeping species healthy, restoration is a retroactive process that rebuilds what was lost. Rather than saying restoration is a type of conservation, it is more appropriate to consider restoration a solution for when conservation and preservation fail. For example, as we continue to lose countless acres of wetlands to urban sprawl and conversion for mass agriculture, rebuilding wetlands becomes critical for healthy migratory waterfowl populations. An example of trying to restore a critter is the reintroduction of bison to tribal lands.

Final Thoughts on Conservation vs Preservation

Preservation is important in a world with an ever-expanding human population that puts mounting pressure on global biodiversity. Conservation addresses the realities and demands of modern life and implements them into resource management. The two schools of management complement each other, even if they are sometimes at odds—much like the two men who championed the approaches over a century ago. But at the end of the day, both approaches seek to protect wildlife and wildlands far into the future.