The Biden administration announced Wednesday its largest habitat protection move yet: the cancellation of seven remaining oil and gas leases in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge’s Coastal Plain and a proposal to ban oil and gas exploration on more than 13 million acres of the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska. The leases in ANWR, which have been suspended since June 2021, were leftover from the Trump administration’s move to open the 1.5-million-acre Coastal Plain region to fossil-fuel extraction. At the time, the decision shocked conservationists, excited Alaskan residents who rely on the oil and gas industry (the largest in the state), and left those who appreciate both feeling conflicted. (More from OL staff writer and Alaska resident Tyler Freel on those complexities here.)

This announcement comes as President Biden approaches what may be his final year in office. The list of U.S. presidents who made sweeping changes to public lands and waters at the end of their presidency starts with Theodore Roosevelt, who established 47 national forests in fewer than six weeks in 1908 and 26 native bird and wildlife habitat reservations in the final week of his term in 1909. Fast forward to the Obama administration, which established and expanded protections in Bears’ Ears, Grand Staircase-Escalante, and Northeast Canyons and Seamounts national monuments in its final hour. While President Trump signed large pieces of conservation legislation into law like the Great American Outdoors Act, his administration largely rolled back protections for public lands. Trump downsized Obama’s monument designations when he took office, and President Biden returned them to their originally-designated size when he arrived at the White House (with multiple climate and environment advisors from the Obama administration in tow). Now, after a term already sprinkled with public lands protections and designations, Biden’s move in Alaska could mark the beginning of a grand finale.

Some leaders in the sporting and conservation community say it will be hard to top this week’s protection of the ANWR and NPRA. Backcountry Hunters and Anglers’ government relations director Kaden McArthur applauds the decision. He also points to the Biden administration’s record since taking office as proof that he’s already accomplished a lot for conservation.

“This administration has been very proactive,” McArthur tells Outdoor Life. “I think the vast majority of its activity in conserving our natural resources and public lands and waters has been continuous throughout the administration. There’s not a significant need to make a buzzer beater move.”

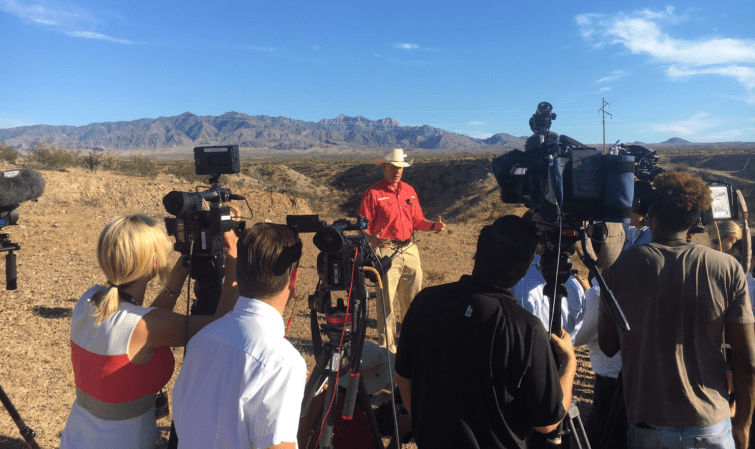

Some of the wins McArthur points out include the recent Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni National Monument designation near the Grand Canyon in Arizona, the 20-year ban on mineral and geothermal leasing in 225,504 acres of the watershed that feeds the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness in January, and the Avi Kwa Ame National Monument designation in southern Nevada in November. Conservation groups like BHA usually prefer to see federal land protected through legislative action rather than executive action, since acts of Congress “have greater buy-in from a broader section of the community and can address more specifics than a monument campaign itself can,” McArthur says. “Monuments are a phenomenal tool but not always as prescriptive as legislative designations can be.”

But Congressional battles are also harder-fought, and McArthur says this might explain why the occasional term-end flood of monument designations occurs: When Congress can’t get it done, the President can. If the Biden administration were to tackle more designations, McArthur and BHA have some ideas of what might be on its list.

“Two others that we are asking the administration to move forward with are an expansion of the San Gabriel Mountains National Monument as well as an expansion of the Berryessa Snow Mountain National Monument,” McArthur says. Both are in California.

He also sees an opportunity for federal protections in the Ruby Mountains in northern Nevada, an area he calls a “sportsman’s paradise.”

“We want to see just shy of 350,000 acres of the Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest withdrawn from oil and gas leasing,” McArthur says. “That region is a critical migratory corridor for mule deer and sage grouse habitat. The administration can not [withdraw that area from oil and gas leasing] permanently, but they can initiate a 20-year withdrawal, very similar to actions taken in the [Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness].”

BHA doesn’t have any sense of timing on these potential moves or even if they will happen at all, McArthur adds. But other conservation leaders also cross their fingers that more habitat protections are on the horizon.

Chris Wood, president and CEO of Trout Unlimited, is enthusiastic about the move, which stands to benefit fish populations. For example, the Coastal Plain of ANWR provides crucial habitat for migrating king salmon and arctic grayling. Wood hopes that the goodwill created among conservationists for protecting ANWR and NPRA will encourage Biden to “rinse and repeat.”

“We have been trying to get a segregation and withdrawal from mineral entry on public lands around the Smith River in Montana, and a similar withdrawal around the Pecos River [in New Mexico and Texas],” he says. “We’ve also been looking at expansions of refuges in Wyoming.”

Read Next: Trout Unlimited Calls on Biden Administration to Save Snake River Salmon and Steelhead

Wood doesn’t necessarily see the ANWR and NPRA protections as a political move. Instead, he sees the Biden administration grasping a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to conserve a massive swath of wilderness. Wood worked on the 2001 Roadless Rule with the U.S. Forest Service, which protected 58.5 million acres of National Forest lands. He considers protecting the ANWR and NPRA the biggest move of its kind since 2001.

“It’s rare that you see the opportunity to protect 13 million acres of land in one fell swoop,” Wood says. “These big conservation initiatives don’t come around very often. I hope it’s a sign of more to come.”

Other groups and entities condemn the move. The state-owned Alaska Industrial Development and Export Authority held the seven remaining leases that Biden canceled. They announced a promise to fight the action on Wednesday, classifying the administration’s decision as “unlawful” and “campaign trail rhetoric.” AIDEA also foreshadows more widespread land protection from the Biden administration before his term ends, which they decry.

“Unfortunately, Alaskans can expect more negative campaign decisions shutting down opportunities for jobs and resource development in Alaska,” the AIDEA Office of Communications and External Affairs writes. “[This] development in Alaska … would benefit the nation with domestic supplies of resources and ensure trillions of dollars appropriated for the ‘green’ economy do not go to foreign countries with little to no environmental standards.”

About the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

The 19.64-million-acre ANWR covers the northeastern corner of Alaska and is the biggest wildlife refuge in America. President Eisenhower established the 9 million acre Arctic National Wildlife Range in 1960 before it was redesignated as a part of a larger refuge in 1980 by the Carter administration. The area remained pristine wilderness until President Trump signed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in 2017, opening the Coastal Plain region to oil and gas exploration.