Multiple conservation and sporting groups with representation in Pennsylvania are sounding the alarm about a last-minute amendment to a fiscal codes bill currently working through the state legislature. By diverting $150 million from the Pennsylvania Game Commission’s Game Fund and redirecting it to a different fund managed by the Department of Agriculture, HB 1300 would have huge implications for Pennsylvania’s ability to finance its wildlife management, the Pennsylvania Confederation of Sportsmen and Conservationists announced earlier this month.

What’s even more problematic is that, by transferring funds away from the PGC, the state could forfeit Pittman-Robertson funding, a cornerstone federal program for supporting wildlife and habitat conservation in all states. But few hunters and anglers—of which the state has many—saw a move of this magnitude on the horizon. That’s especially true since diverting PR funds to other uses technically violates federal law, Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation director of government affairs Ryan Bronson tells Outdoor Life. (He points out that Pennsylvania is an elk state, too.)

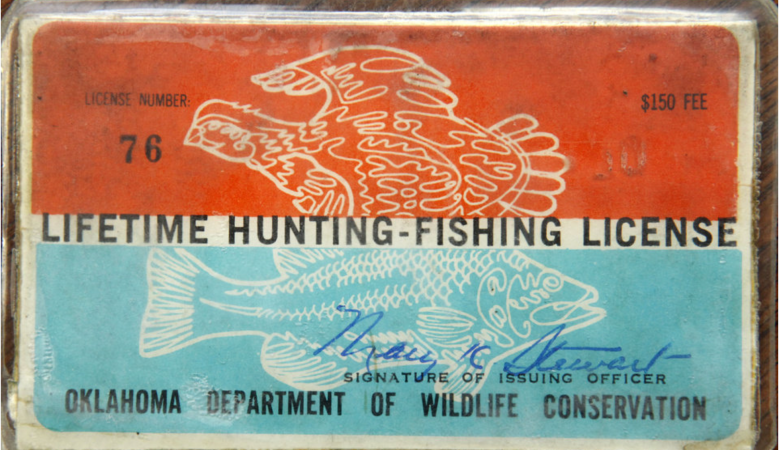

“In order to receive their apportionment [of PR funds], a state has to generate enough revenue in hunting license fees to earn that match,” Bronson says. “If they ever misuse their allocation [of PR dollars] from the federal government, the feds have the ability to withhold and penalize the state for being in breach. That’s been in the Pittman-Robertson Wildlife Restoration Act since 1837, and it’s one of the key reasons that the model has protected hunting licenses for so long.”

Understanding How Pittman-Robertson Works

State wildlife agencies get access to federal PR dollars annually by putting up money of their own as “match.” This money comes from hunting and trapping license sales and revenue derived from state-owned lands. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service determines how many PR dollars each state gets, a figure that is determined by both a state’s size and population of hunters, Bronson says.

The PRWRA was written so that federal PR dollars would shut off automatically if a state tried to funnel them toward education, transportation, or other non-wildlife uses, he explains. By taking a lump sum from the Game Fund and putting it into the Clean Streams Fund, which was created last year with $220 million from the federal American Rescue Plan Act, not only would PGC almost certainly lack the money to match and receive PR funds for the foreseeable future, but the agency would also be in direct violation of the PRWRA itself.

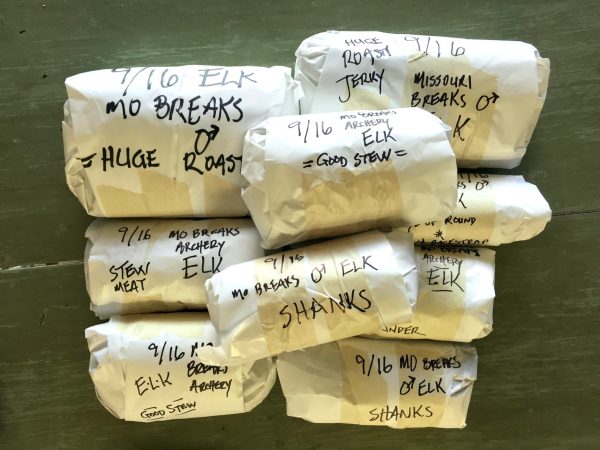

Part of the $150 million in question came from oil and gas leases on Pennsylvania game lands, which the PGC used its PR dollars to buy in the first place, Bronson says. The PRWRA requires that revenue generated from lands purchased with PR dollars go straight back to the state’s PR fund. This closes the feedback loop that the North American model of wildlife conservation thrives on; money derived from past PR activity goes toward PR’s future purchasing power and resulting conservation footprint.

USFWS, which administers the PR program, wrote a letter to PGC executive director Bryan Burhans on Sept. 1 to raise the issue.

“License revenue must be controlled by [the PGC] and used only for the administration of the PGC,” FWS assistant regional director of the Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration Program Colleen Sculley writes. ”If PGC loses control of license revenue or license revenue is used for purposes other than the administration of the PGC, the Service may declare your agency to be in diversion and ineligible to receive PR-Wildlife Restoration Program funding.”

PR’s conservation footprint in Pennsylvania is no small thing. Due to its size and population of hunters, Sculley points out in her letter, the PGC received over $41 million in PR dollars last year.

Funding for Agricultural Projects

The Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture manages the Clean Streams Fund, which was created last year with $220 million from the federal American Rescue Plan Act. The fund aids farmers and ranchers in affording improvement projects to reduce runoff, erosion, and sedimentation in streams adjacent to their land. Such projects are intended to help fish and wildlife and the ecosystems they rely on, especially in the Chesapeake Bay.

“While we can all agree that the Clean Streams Fund is a worthy cause, why should it be funded only by hunters and trappers?” PCSC asks in their press release. “Especially when the state is sitting on a [$13 billion] surplus.”

Pennsylvania state chairman for Ducks Unlimited Chad Hohenwarter points out that, when hunters spend their money on licenses and equipment, it supports all of Pennsylvania’s wildlife.

“This would be devastating for wildlife conservation in our state,” Hohenwarter says. “I am appalled that hunter dollars, used to conserve all wildlife species, would be taken away from us and used for other purposes.”

Read Next: Sportsmen, Gun Owners Generated a Record $1.5 Billion in Conservation Funding Last Year

HB 1300 passed the Senate on Aug. 30 and went to committee on Sept. 22. Bronson guesses that the implications of the amendment weren’t immediately clear to the legislators who introduced and voted for it. The Pennsylvania House of Representatives returns to session tomorrow to reconsider the Senate-passed version of the bill, which includes the amendment. But Bronson is optimistic.

“I think the odds are pretty good that the legislature is going to correct this,” he says. “The implications were probably not clear when they passed [the bill], but hopefully it is clear now that the Pennsylvania game agency will be devastated. They’ll lose a third of their Game Fund from the original appropriation but then they’ll lose $40 million a year every year going forward. Wildlife management [would] change dramatically as a result.”