If I were a betting man, I’d wager that many of you who target species like trout and smallmouth bass in river systems have experienced fluctuations in action within certain stretches over the years. A piece that was fire when you were younger might not produce like it used to, while a stretch miles away suddenly seems loaded when it had been a dead zone in the past. I’ve been going through this on my home river, the Delaware, for roughly five years now. The smallmouth fishing down the street was great for most of my life, but in recent years it’s tapered off dramatically. Just 20 miles upstream, however, the fish remain plentiful. Why?

A number of environmental factors can contribute to a boon or dearth of fish, but when things seem bad on a home stretch, we assume that eventually balance will be restored. We tell ourselves that for whatever reason, the fish just moved up or down stream, and eventually they’ll repopulate and things will normalize. A recent study, however, suggests that river fish don’t move around as much as we think. Furthermore, it suggests that fish within different parts of a river don’t co-mingle as much as many people believe. The research is fascinating, and it could shed new light on how we monitor the overall health of a watershed.

Fish Create Genetic Countries

The study was conducted on the White River, which flows for 722 miles through Missouri and Arkansas before meeting the Mississippi River. According to PHYS.org, biologists from the University of Arkansas surveyed 31 species of fish from 75 locations along the White. By studying the genetic variations between the same species existing in different parts of the river, they learned that the fish created their own “genetic boundaries.” In other words, populations of fish remained largely confined to their home turf.

“Just as our ancestors were more likely to have close relatives nearby, so also have fish, thus creating regionally distinct genetic ‘countries,’ shaped by unique environments,” Zach Zbinden, a post-doctoral research associate who carried out the research as part of his doctoral dissertation, said in a statement.

The research team also learned that fish within one section of the river had varying genetic adaptations that better suited them to handle environmental factors in their home stretch that may not be the same up or down stream. This information could change your perspective if you’ve always thought of a river as a unified body of water with inhabitants that roam freely.

Fisheries Management Implications

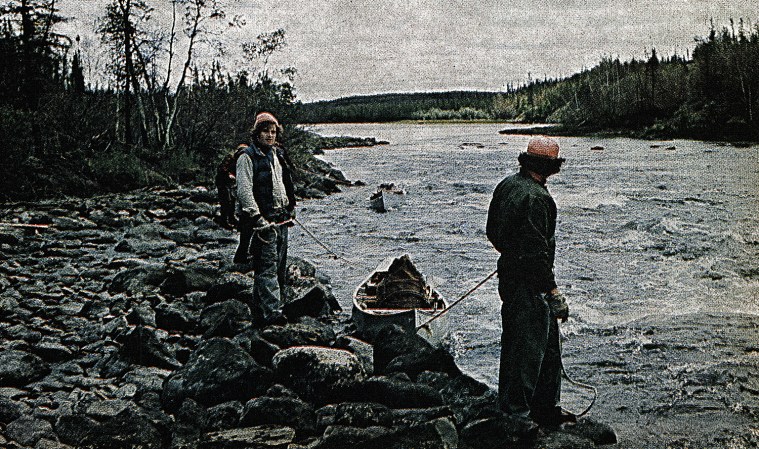

Photo by Joe Cermele

My biggest takeaway is that you can’t rely on a strong population of fish in one area to repopulate another area that’s lacking life. In the case of the Delaware where I chase smallmouths, this research potentially paints a bleak picture for my home stretch of water. Local anglers might chalk the decline up to everything from a few high-water events during critical spawning periods, to an influx of invasive flathead catfish, to rising water temperatures in the central and lower parts of the system. However, the bottom line is that if the population is diminished, it doesn’t matter how strong it is 20 or more miles upstream. Smallmouths from that area are not likely to move down nor breed with my local bass. This knowledge, however, is useful to fisheries managers.

Those involved in the White River study are hoping their findings will lead to a more “holistic understanding of the complexity of river networks.” If so, it could provide tools for managers to parse out sub-populations of fish and draw a tighter bead on what specific areas within the system need in order to stay healthy. This is particularly useful when implementing stocking programs.

It’s not uncommon for stocked trout to share a river with wild trout. This ruffles a lot of feathers among those who dislike hatchery fish and want more effort put in by states to protect wild trout populations. In many regions, of course, this creates conflict. Stocked trout boost license sales, whereas in many states, the wild fish are much smaller and often found closer to the headwaters of a river. With a better understanding of wild trout populations per section, however, it seems reasonable to assume that smarter decisions on where to stock—and where not to stock—could be made. Similarly, states that stock channel catfish, walleyes, and other species in rivers to bolster wild populations could determine where the boost is needed most and where overcrowding might occur.

Read Next: Why We Love (and Hate) Hybrid Game Fish

Most critically, looking at specific and unique populations within a river could also help managers create more localized regulations. It could be determined that by shutting down a fishery for a few seasons in one stretch, or reducing the bag limit in a specific area, there will be greater long-term good for the entire system.