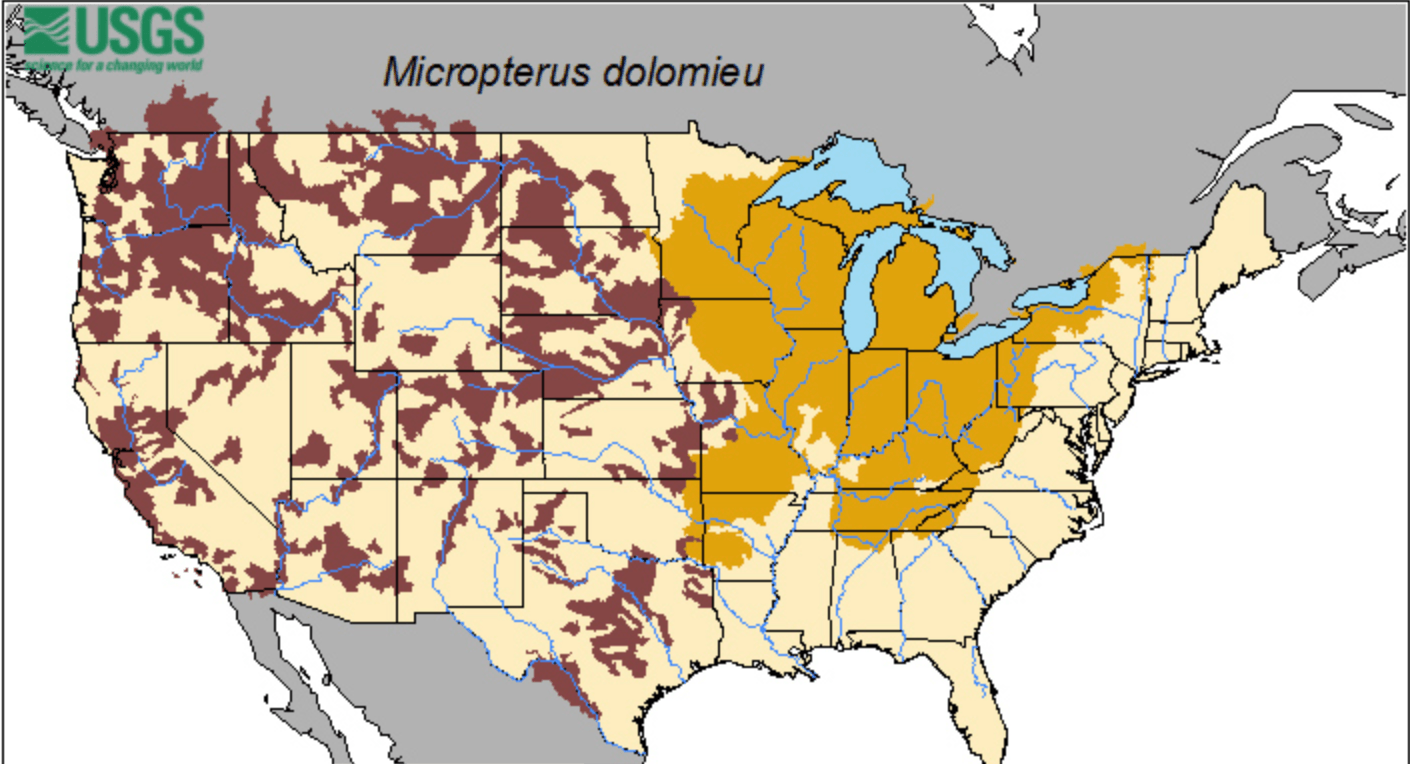

Smallmouth bass rank high up on the list of most popular fish species in America. Though they fall short of the distribution range of the largemouth bass—America’s most popular gamefish—they’re still accessible to millions of anglers. From the Great Lakes up North to the deep reservoirs of the Mid-South, Northeast streams to the mighty rivers of the Pacific Northwest, “bronzebacks” have become stars in so many regional fishing cultures. Because of this, it’s easy to forget they actually don’t belong in many of the places we catch them.

Of course, the same can be said of our beloved largemouth bass, walleyes, and both brown and rainbow trout. Those brown trout came over from Europe and would have never occurred here naturally. Rainbows were native only to the Pacific Northwest; largemouth are native to only the southeast and Midwest (from Florida ranging up to southern Minnesota). As for smallmouth, they were originally native to the Great Lakes and Ohio River drainage within the U.S., but spread throughout the Mississippi River Basin naturally on their own. Everywhere else they are found, someone put them there at some point in history—or at least put them somewhere close by and they propagated and expanded their range on their own.

Smallmouth In the Grand Canyon

This is not to say that transplanting fish is a bad thing, as it’s created tremendous fisheries across the country, which in turn have boosted everything from tackle sales to motel room rentals to the pay checks of the biologists working at hatchery facilities. For the most part, stocking and transplanting fish are well calculated endeavors, but problems arise when transplants end up in waters they’re not supposed to be. And despite our general love of the smallmouth bass, the reality is that they are one of the most destructive and disruptive fish in the country, causing more worry in many regions than even dreaded invasives like snakeheads and Asian carp.

Most recently, smallmouth bass are creating major concern in Arizona. According to this story on Azcentral.com, smallmouths, along with several other non-native species, were stocked decades ago in Lake Powell, which is an impoundment of the Colorado River. The transplants took place to boost recreational angling on the lake and were highly successful in doing so. For years, everything was great, but a combination of recent droughts and overuse of the Colorado as a commercial water source have created problems. As the story puts it, “The Southwest’s thirst for the drying river is pushing a challenged aquatic environment further out of whack.”

Lake Powell is held back by the famed Glen Canyon Dam, and every day the water level behind it is getting lower and lower. Biologists fear that the muted flows will make it more likely for smallmouths to slip through the turbines, and if that happens, it will introduce smallmouths to the Grand Canyon. Biologists netting at the lower end of Powell are routinely capturing smallmouths close to the dam. A handful of bass captured in riverside sloughs below the dam suggest that it may already be too late.

What’s at Stake?

If smallmouths get a stronghold in the Colorado River below Glen Canyon, it could spell doom for many native species that biologists are already working hard to protect—they’re trying to keep the heritage of the Grand Canyon ecosystem intact. In particular, fisheries managers fear smallies could completely wipe out the native humpback chub population, a species only recently upgraded from endangered to threatened.

Arizona has already put a bounty on brown trout below the dam for the same reason, but the trout won’t venture too far downstream of the dam and the cold water it spills. Smallmouths are a warmwater species that can and will set up shop anywhere they want.

Part of the reason anglers love smallmouths so much is for their voracity, and it might be easy to say, “who cares about some chubs?” The reality is that transplanting has disrupted native species like the humpback chub all over the country. It’s just that we tend to treat fish we can’t or don’t target with a rod and reel as expendable. But what if smallmouths threatened one of the most famous trout fisheries in the world? That’s what happened in February when smallies were captured in Montana’s Gardner River, a tributary of the Yellowstone at the doorstep of Yellowstone National Park.

Then there’s Maine, which has spent countless time, money, and resources attempting to eradicate errant bass from systems that foster wild trout reproduction. Eradication efforts are also taking place in Manitoba, Oregon, ponds in Montana…I could go on.

The lesson here is that just because a fish is deeply engrained in our national fishing culture doesn’t mean more is always better. Likewise, a fish’s popularity shouldn’t allow us to ignore the problems it may be causing. Most of us wouldn’t see any issue with catching a nice smallmouth in a stream or river where you’ve never caught one before, but doing so could actually be cause for alarm.