Archaeologists have found a collection of prehistoric flutes in northern Israel that could provide some insight into how early humans hunted birds. In a paper that was published in Scientific Reports this month, researchers conclude that the 12,000-year-old flutes were made from duck bones and were used to imitate the calls of certain birds.

“…these objects were intentionally manufactured more than 12,000 years ago to produce a range of sounds similar to raptor calls,” the study’s authors write.

The authors suggest that the flutes could have been used to communicate or played as musical instruments. But there’s a third explanation, which is that humans used these tools as rudimentary calls for bringing birds into hunting range.

Turning Duck Bones into Flutes

The flutes were discovered at a cultural site in Israel’s Hula Valley known as Eynan-Mallaha, which was home to the Natufian culture. The Natufians lived in modern-day Israel, Jordan, Palestine, and Syria approximately 11,000 to 15,000 years ago, and they were “the first hunter-gatherers in the [region] to adopt a sedentary lifestyle,” according to the study’s authors.

A previous excavation at Eynan-Mallaha in the early 2000s yielded more than a thousand individual bird bones, many of which were found in dwellings and gravesites. This indicated that the Natufians hunted birds—particularly waterfowl—for food and other uses.

The ancient people subsisted off wintering waterfowl and also hunted “birds of prey for their talons,” the authors write, adding that the talons “might have been used as tools or for ornamentation.”

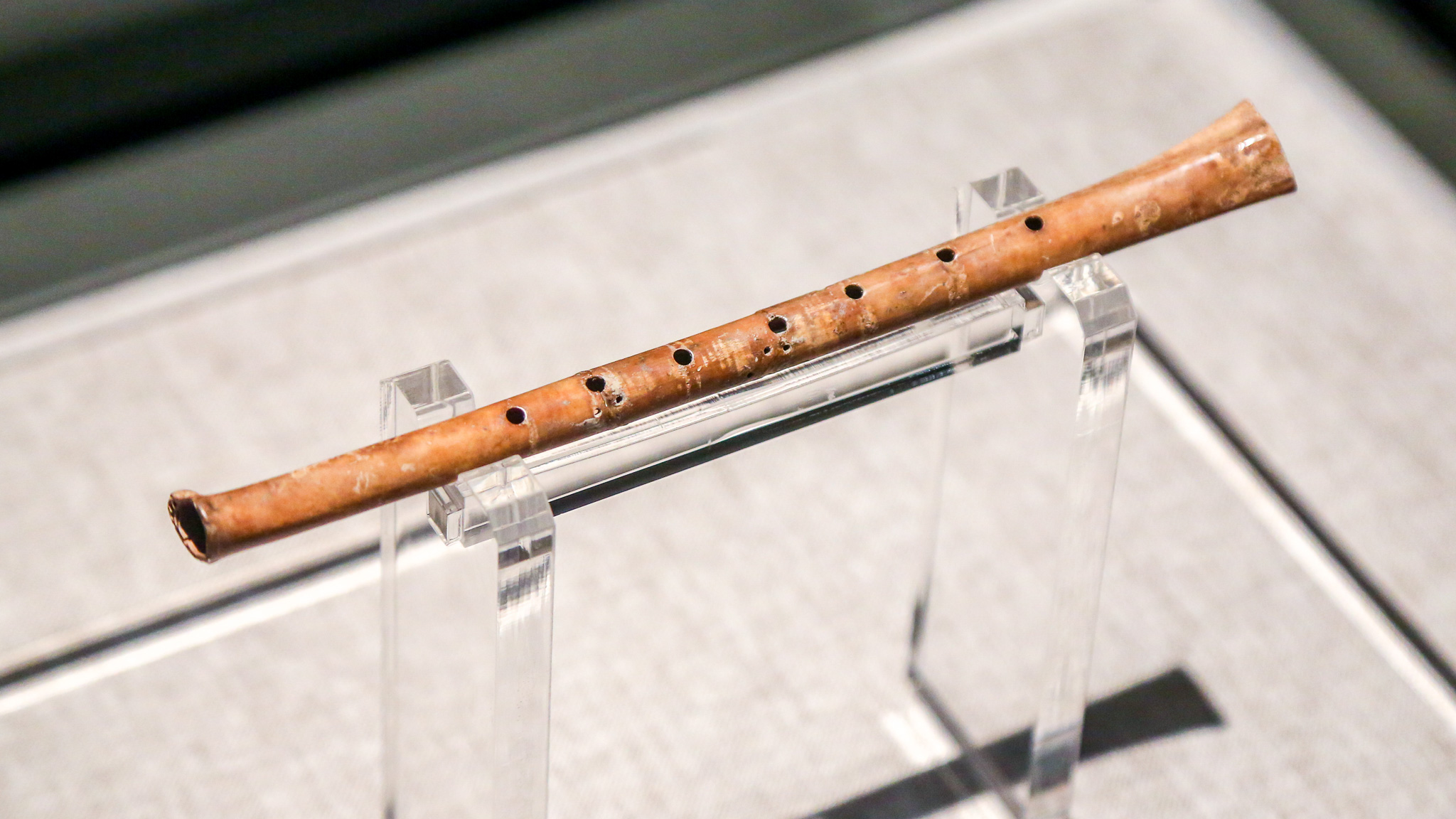

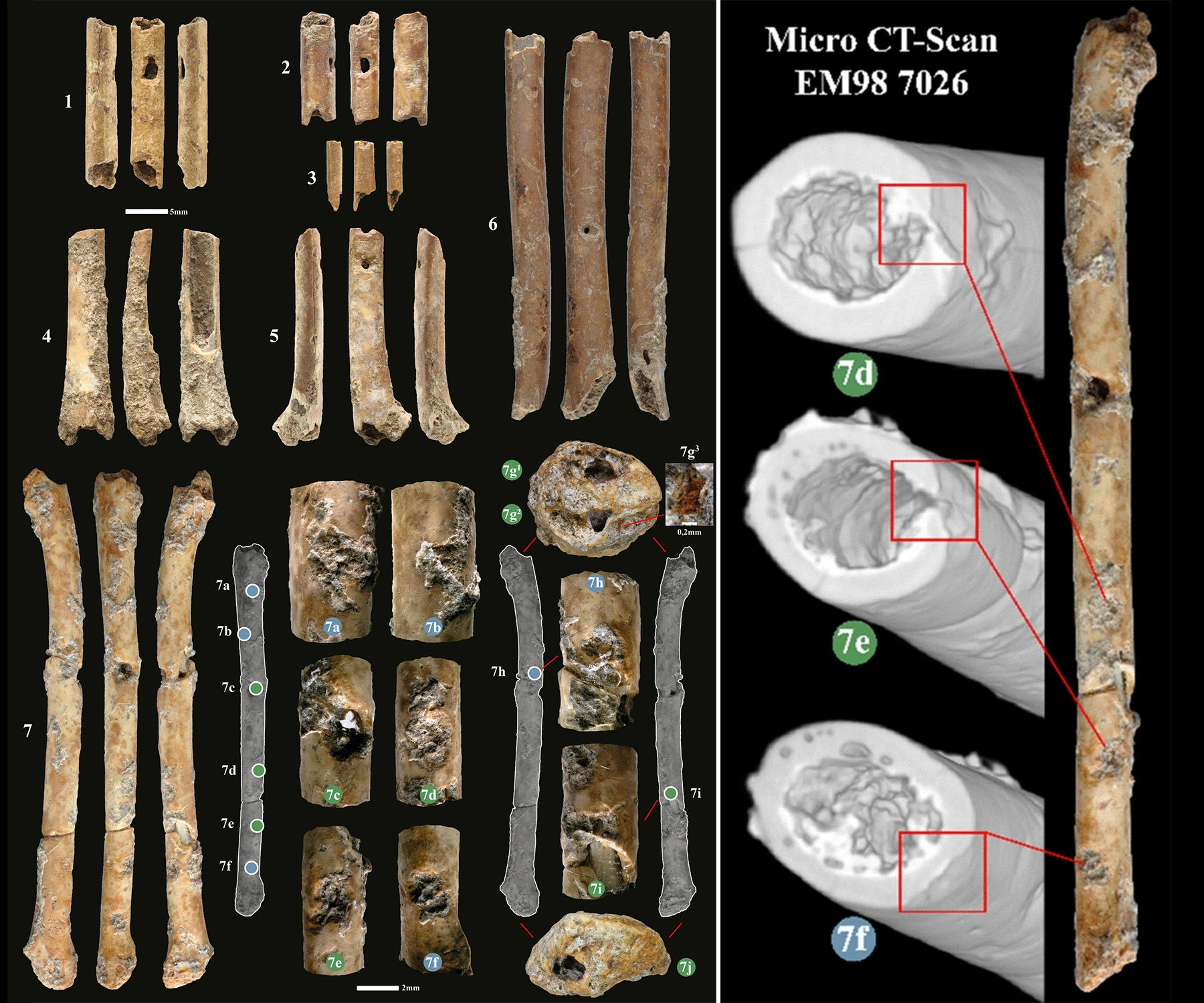

It wasn’t until archaeologists re-evaluated these bird bones last year that they made a new discovery: some of the bird bones had holes bored into them. They identified one intact wing bone and six other fragments of worked wing bones that featured mouthpieces and multiple finger holes. All of them had signs of wear indicating they had been used, which led the authors to identify the tools as “aerophones,” or wind instruments.

The instruments were all less than three inches long, and further analysis revealed that the bones came from Eurasian teal and coots. The Natufians evidently hunted for these ducks along with “other, larger species, such as birds of prey, larger waterfowl (geese, swans), and especially the mallard,” the authors explain.

Read Next: Archaeologists Discover Ancient Arrows and Hunting Blinds as Glaciers Melt in Norway

“They are probably some of the smallest prehistoric sound instruments known today,” lead author Laurent Davin told LiveScience. “Because of residues of ocher, we know that they were probably painted [red]. Because of the use-wear we think they might have been attached to a string and worn.”

Calling in Birds

So, how did the Natufians use these small wind instruments that they wore on lanyards around their necks? To find out, researchers made replicas of the flutes using mallard bones. They reproduced “high-quality and high-pitched notes” with the replicas, which led to their ultimate hypothesis: “that the purposes of the sound produced were to imitate bird calls.”

When they analyzed the notes, however, the authors concluded that they weren’t meant to imitate ducks, after all. Instead, they found that among the 58 bird species found at the site, the frequencies produced by the flutes were most similar to the calls of two raptor species.

“We, therefore, believe that the aerophones were made to reproduce the calls of the valued Common kestrel and Sparrowhawk,” the authors write.

The authors believe the prehistoric birds calls were likely used as instruments, which reinforces the idea that our understanding of music evolved as hunter-gatherer cultures adopted more sedentary lifestyles and established villages. But these bird-bone flutes might have also played a valuable role in hunting.

“The Natufian’s manipulations of sounds might have functioned in various aspects of their socio-cultural lifeways, either for hunting, communication, or ritualised behavior,” the authors conclude. “They could have been meant as a decoy used to lure the Common kestrel and Sparrowhawk to facilitate their hunting (i.e., luring birds within shooting distance by imitating their sounds).”