My eyes followed the aim of Dan Ardrey’s binocular but I saw nothing at first. “Way out there by that windmill,” he pointed out. I could barely even see the windmill with my naked eyes, but through the 10X glasses, I could finally make out a gray dot moving steadily over the brown and yellow grass. It was a mule deer, and even without seeing the antlers, we knew it was a buck. No doe would ever set out on such a midday march.

For 20 minutes, we watched as the buck transformed from a gray dot three miles away into a respectable trophy that entered the pine trees several hundred yards below us. Only after he ducked into the timber did the buck slow down and start nosing around. In those 20 minutes, I received one of the most valuable lessons in mule-deer hunting of my life.

CHALLENGES OF OPEN SPACE

That buck had traveled at least four miles from the nearest cover before we even saw him. The entire seven miles took him less than an hour, and he covered the distance without seeming too concerned about anything in his surroundings. Plains muleys are homeless nomads. Mule deer don’t move back and forth in aimless fashion as whitetails often do. They tend to travel in a line or perhaps a big circle.

In the High Plains, mule deer eat grass and sage and browse on the fresh greenery of junipers and other small trees. Many of the native prairie grasses, in particular, are high in protein and are all the deer really need. Everything mule deer walk on is food, and the animals don’t seem to play favorites in what or where they eat.

Rarely will mature bucks focus for more than a day or two on a single food source, no matter how attractive it seems to a hunter. Mule deer might feed for a few days in one place but then abandon that food source for three weeks–or three months. Their greatest defense in this country (at least against a bow) is their unpredictability.

I wasn’t sure what to expect when I went bowhunting with Ardrey. He had seen two great bucks entering an alfalfa field to feed on different days in early September, but they disappeared and he hadn’t seen them again by the time I arrived in early October. As I climbed into a stand near that spot, my hopes were low, but I had a mood swing within several minutes when I watched several bucks–three of them very big–run into the alfalfa field an hour and a half before sunset.

I blinked a few times to clear the cobwebs, but there they were: mule deer chest-deep in the lush green field. A barrel-chested brown-horned buck immediately caught my eye. There were also other big ones, but had I been given the choice, I’d have taken Ol’ Brownie. I didn’t want to risk spooking the bucks by trying a stalk to the edge of the field, but had I known then what I know now, I would have gone for it. I thought the smart play was to be conservative and wait until the next day so I could move my stand closer to the trail they used. I was thinking like a whitetail hunter.

A PLAN COMES TOGETHER

Watching from a distance the next evening, my guide saw the bucks milling back in the cover 150 yards north of my newly moved stand. The following afternoon they came out in the field 400 yards south of me. The fourth evening they came out 250 yards to the south.

They were still in the area, but maddeningly unpredictable for a man with a bow. My fifth evening in that stand would be my last. I had to go home at some point, I knew. Shortly after lunch, I went out to shoot my bow, full of nervous energy. I checked the wind a dozen times. Each time the dry brown grass drifted toward the south–perfectly wrong for the stand. I decided to try it anyway, hoping for a miracle. The wind brushed the back of my neck for two and a half hours and nothing moved. Finally, just as the sun dropped behind the hills, the wind died and the thermals reversed.

Not two minutes later, I saw gray forms hustling through the trees and headed for the field. Fortunately, the wind was now cooperating, but unfortunately, the bucks had chosen a trail that was 70 yards away.

Minutes after the deer hit the field, I saw my guide begin walking into the field from a quarter mile away. At least one of the big bucks had to be in this group, I thought. I hoped that his antlers were big and brown. As the guide drew closer, he circled slightly into the cover and began to whistle softly as he approached.

I expected to see gray streaks at any moment, but instead the soft push worked like a charm. The bucks came my way at a swift walk, the brown-horned buck in the lead.

Light was fading fast as I struggled to line my pins up on the dream buck, which stepped into the only shooting lane I could see. When the arrow thumped him at 40 yards, it made a hollow sound, like I’d punched a watermelon. I knew it was a solid hit. He kicked up his back hooves and peeled away from the group at a full run. We later found the buck lying dead 125 yards from my stand.

This hunt illustrates two important points. First, mule deer are unpredictable. Ardrey hadn’t seen the bucks for a month, but all of a sudden there they were. Lucky for me that they decided to return while I was there. Second, if my guide hadn’t been there to move the deer toward me, I never would have gotten a shot.

STRATEGIES FOR PLAINS BUCKS

A rancher might go on for hours talking about the huge buck he saw three days ago. As a whitetail hunter I want to dash right in there and put up a stand, but I’ve learned to resist such temptations when hunting mule deer. Until I actually see the deer and can study the situation carefully, I keep all options open and don’t tie myself to one spot. The key to success is to find the buck where he is right now and then hunt him.

Cover a lot of ground, glass known deer hangouts every evening and every morning until you find a buck you want. Assuming you locate him in a place you can hunt, four practical hunting strategies are available:

SPOT AND STALK Stalking to within bow range in open terrain is never easy. I’ve spent entire days lying behind a sage bush on thinly grassed knobs just 100 yards from a big buck, waiting for him to drift my way. In most cases, he never did. If the buck is alone you’ve got a decent chance of slipping in close enough for a shot, but bucks are rarely alone and more than one pair of eyes and ears will be watching and listening for the approach of danger. With a gun, it’s game over for the muley if you’re in reasonable range, but with a bow the stalk approach is generally my second choice. I only try to close the deal with a stalk when there is no way to set up an ambush in the buck’s line of travel.

AMBUSH

The ambush method is sort of like a stalk-and-wait approach. After spotting a buck in the morning, watch carefully where he beds, get as close as possible to his likely exit route and then wait for him to resume his daily routine.

Wherever a buck beds, he is likely to leave going in the same direction he was originally headed. Bucks browse on a variety of natural foods; there’s usually no reason for them to backtrack. Only when there is a very specific food source nearby or a feature of the terrain that controls movement will the buck possibly leave the bedding cover the way he entered.

STILL-HUNT In some parts of the West, where the terrain is dry and crisscrossed with canyons, it’s common for mule deer to bed down in small canyons or in fingers that split off from a main canyon. Sometimes it’s possible for a bowhunter to slowly and silently still-hunt such a canyon and scan the terrain ahead in hopes of seeing a buck’s antlers. Then it’s a matter of trying to get in position for a shot before he detects you.

SOFT PUSHES

I’ve taken mule deer (and big whitetails too) with my bow on the plains by resorting to soft pushes. Keep the effort subtle. Ask a companion to get the deer standing (but not to drive them) as you wait nearby and hope for the best. Sometimes it works, but usually it doesn’t. This is the strategy of last resort, once you’ve determined that nothing else will work and you’re desperate.

Mule deer of the High Plains have a unique behavior and offer a thrilling challenge that makes them nearly irresistible. I love to hunt whitetails, but going one-on-one with a plains monster gives me a rush that few whitetail hunts can match. It is one of bowhunting’s ultimate thrills.

Spot-and-Stalk Tips

1. Hunt in pairs whenever possible. Two sets of eyes will see more game, and when you spot a trophy buck, one hunter can stay back to give hand signals to the stalker.

2. If a stalk starts to get dicey in the final approach and the muley looks nervous, be patient. Wait until things calm down before proceeding.

3. If you’re hunting for a trophy, carry a compact spotting scope and a tripod. Long-range field judging will allow you to use your hunting time more efficiently.

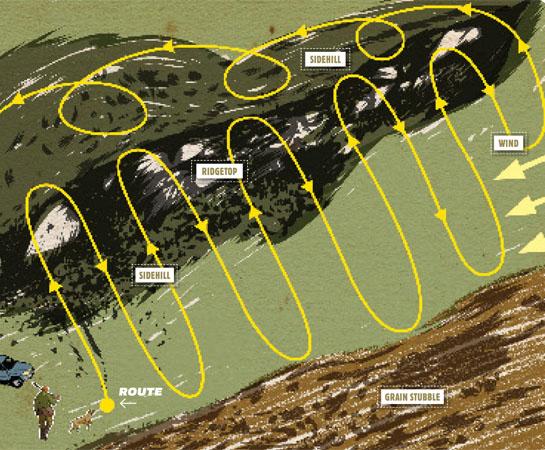

4. Use grass clippings to test the wind regularly. Account for the effects of thermal currents when hunting hilly terrain. Approach bucks from uphill in the morning when thermals are rising.

5. Stalks should always start fast and end slow. Get within 100 yards as quickly as you can and then slow down.

Walk Softly On the Plains

My favorite footwear for stalking mule deer over the crunchy plains is a pair of inexpensive Chucks-Converse All-Star high-top basketball shoes. For hunters who are more particular, Cabela’s offers a similar design in camouflage called the Silent Stalk Sneaker. (www.cabelas.com)

If you are stalking in areas where a carpet of small stones makes footing even noisier, remove your boots for the final 40 yards and replace them with a thick pair of wool socks. You can also put on a pair of noise-muffling thick-pile stalking booties over thin boots or shoes. Examples include Cabela’s Baer’s Feet or Sneeky Pete Feet from PSE. (www.pse-archery.com)

Silence is crucial during a stalk. If your boots have hard soles, consider using a pair of noise-muffling stalking booties.

QUICK FIXES

Bug Stopper To ward off flies and other insects, spray the body cavity of a deer or other field-dressed big game with a mixture of lemon juice concentrate (60 percent) and Tabasco sauce (40 percent).