At first glance, the cover of the April 1998 National Geographic seems innocent enough-charming even. But on closer inspection, an eerie discordance becomes evident: One of the two prairie dogs is disappearing facelessly into the mist while the other raises its paws beseechingly. A tag line reads, “The Vanishing Prairie Dog.” If you find this combination of picture and words unsettling, you’re reacting as intended, because the cover is a masterpiece of anti-hunting psycho-propaganda.

Inside, a 16-page article begins with an emotional description of a prairie dog’s death by speeding bullet (“the animal becomes airborne as smithereens of whirling flesh…”) and then goes on to depict prairie-dog shooters as loathsome louts, along with the ranchers who want dog populations controlled.

Though poisoning is mentioned in the National Geographic article (which is made up mostly of heart-tugging pictures of the cuddly creatures), nowhere is poison described as the great eliminator of prairie-dog towns. Nowhere is the prolonged agony of death by poison narrated in the crimson detail reserved for instant death by bullet. And nowhere are poisoners of prairie dogs depicted in the scurrilous characterizations heaped on hunters.

The motives of National Geographic are so transparent that the whole thing would be laughable, were it not for the magazine’s wide readership and otherwise well-earned respect. The article is anti-hunting, pure and simple-the same old anti-hunting/anti-fishing (it’s morally impossible to be one and not the other) hype in a new set of fur. And it’s not just about saving prairie dogs. You see, the prairie dog is the “New Bambi”-symbol of all animals that are hunted, from deer in Minnesota to quail in Georgia.

Veterans of anti-hunting wars will well remember the Don’t-Kill-Cute Bambi ploy that was once used so effectively against deer hunters, especially among the non-hunting populations of the crowded Northeast. But when burgeoning deer herds invaded suburbia, eating gardens, shrubs, flowers and trees and causing thousands of auto accidents, Bambi became a menace and no longer a pretty poster child for the anti-hunting/fishing cults and comrades.

Thus the cuddly prairie dog becomes the Bambi for the new century, and a pretty smart one at that. After all, they dwell out West where they will never be seen by the vast eastern establishment except in cute pictures. What sins could such harmless and cuddly doggies commit? And who could possibly wish them evil except cruel hunters who wipe them out by the thousands, and greedy ranchers who begrudge them a few blades of grass? In return for their spots on the planet, prairie dogs reward our environment with burrows that, among other things, according to National Geographic, provide safe haven for rattlesnakes, black widow spiders and the Easter tiger salamander. Excuse me?

And, of course, they also willingly sacrifice themselves to the all but defunct black-footed ferret, which, after a $15 million “restoration” program, has cost U.S. taxpayers more per animal than a Rolls Royce. Go figure.

A Happy Coincidence?

The National Geographic tirade might easily be written off as a momentary lapse of editorial judgment were it not for the March ’98 issue of Smithsonian magazine, which also shows on its cover a fluffy prairie dog, along with the tag line, “Prairie Dogs Need a Few Friends.”

The articles in these two Washington, D.C.-based publications are amazingly similar-right down to photos of the same prairie dog “rescuer,” who is unmistakably identifiable by a clinched-fist “earth first” tattoo on his arm and shoulder. So if you believe that the back-to-back publication of these two “save the prairie dog” features was only a coincidence, I have some nice waterfront real estate on the moon you’ll want to buy.

The final proof that these two articles and their heartending covers were part of a well-planned anti-hunting campaign came in July, when the National Wildlife Foundation (which is funded in part by sportsmen who still believe the NWF is looking after their interests) petitioned the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to declare the black-tailed prairie dog a threatened species. If NWF’s petition is successful, it will mean that sport hunting of prairie dogs would become unlawful, as would controlling their numbers by poisoning or other means. Landowners would be powerless to protect themselves even as they watch expanding dog towns ravage income-yielding farms and ranchland into crater-pocked moonscapes.

It almost seems that the NWF somehow conspired with National Geographic and Smithsonian to launch the “New Bambi” into public consciousness, especially with National Geographic’s tender coverage of a “made-for-TV” prairie-dog rescue and its quotes from prairie-pup protectionist Michelle Alley-Grubb, who sees her major purpose as not to rescue the rodents but to persuade the public to coexist with them.

“You don’t have to kill prairie dogs,” National Geographic quotes her as saying. Hers and similar “rescue” operations are little more than media photo ops. Further evidence of this media manipulation is provided by a photo of a “rescue mission” in Smithsonian that shows no fewer than three network TV cameras in attendance. But don’t call this objective, or even thorough, reporting: No mention is made that the “rescued” dogs may be transported to places where their chances of survival are nil.

The sophisticated mendacity of NWF’s approach is apparent in its constant reference to the “black-tailed” prairie dog as if it were a dwindling subspecies in dire need of protection. Actually, the black-tailed variety is the most common prairie dog of all, ranging over western states by the millions upon millions. Also, the term “black-tailed” sort of brings to mind the endangered “black-footed” ferret. Get it?

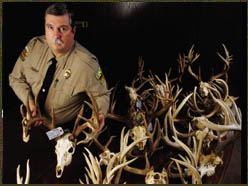

A Shot at Hunters

It’s no secret that varmint hunting-especially prairie dogs-has enjoyed considerable growth in recent years. Current gun and ammo catalogs list more varmint hunting equipment than at any time in history, and related services-guides, lodgings, etc.-are booming. Some ranchers now consider the income from prairie-dog shooters on a par with other ranch products.

So if prairie dogs are declared a threatened species-don’t laugh, this is the object of the New Bambi program and a distinct possibility-a large segment of the hunting population will be disenfranchised overnight, and an important part of the sporting-firearms industry will crumble-a prospect that no doubt causes much giddiness among anti-hunters/fishers and gun-control advocates.

Prairie dogs are only a tactical stepping stone in their overall strategy of ending all sport hunting and fishing. And without sport hunting, the anti-gunners would rise to claim that there is no further legitimate purpose for gun ownership by citizens. Thus anti-hunting/fishing and anti-gun agendas fit together very neatly. This time, though, they dealt us a better hand than they intended, because the fact of the matter is that at present the recreational shooter is the prairie dog’s best friend and its best hope for long-term survival.

The Sad Truth

Though National Geographic and Smithsonian, and especially the NWF, were careful not to make this fact known, many ranchers refrain from poisoning prairie-dog towns on their lands (i.e., total elimination) because shooters keep the dog populations in check. Also, prairie-dog hunters united in responsible organizations such as the Varmint Hunters Association (800-528-4868) have led the fight against mass dog-town poisonings and saved millions of prairie pups from agonized annihilation. Where is the protectionist who can make a similar claim? And for every bullet that is fired at a prairie dog, a percentage of its cost, and that of the rifle that fired it, helps pay for maintaining all wildlife via Pittman-Robertson funds. C’mon, National Geographic and Smithsonian, how could you let that all-important tidbit slip through your editorial cracks? Or were you just suckered by NWF con artists?

A tragic irony of the NWF’s petition to declare the prairie dog a threatened species is that if it succeeds it will, in fact, cause the immediate death of untold millions of prairie dogs and total elimination of many vast dog towns.

When the head of the NWF announced his petition last July, I happened to be in South Dakota, a major prairie-dog state, and was able to get reactions of landowners firsthand. One rancher pretty well summed up the reaction of ranchers all over the West when he told me that he doesn’t believe in poisoning prairie dogs and has relied on sport hunting to keep their populations in check. Without this control a typical dog town on his ranch will expand about 20 acres per year. Multiply this by the number of dog towns scattered across any large ranch and the loss of income-producing grazing land becomes really serious.

“If prairie dogs are declared threatened I will lose my right to control them,” he told me, “so I will have no choice but to completely poison them out before the law goes into effect. My neighbors will be forced to do the same thing.”

I am not of vindictive spirit and admit without hesitation that I will continue reading National Geographic and Smithsonian, for they have much to offer. Charitably, I feel that the senior editors of these fine magazines were simply duped by a cabal of lesser lights with anti-hunting/fishing agendas. So we invite them, and all other mis- directed protectionists, to join outdoor life in educating the public to the fact that hunters are the best friends the prairie dog will ever have, and that recreational shooting is the only humane way to hold their numbers within acceptable limits while at the same time guaranteeing healthy, disease-free populations for future generations to enjoy. s fired at a prairie dog, a percentage of its cost, and that of the rifle that fired it, helps pay for maintaining all wildlife via Pittman-Robertson funds. C’mon, National Geographic and Smithsonian, how could you let that all-important tidbit slip through your editorial cracks? Or were you just suckered by NWF con artists?

A tragic irony of the NWF’s petition to declare the prairie dog a threatened species is that if it succeeds it will, in fact, cause the immediate death of untold millions of prairie dogs and total elimination of many vast dog towns.

When the head of the NWF announced his petition last July, I happened to be in South Dakota, a major prairie-dog state, and was able to get reactions of landowners firsthand. One rancher pretty well summed up the reaction of ranchers all over the West when he told me that he doesn’t believe in poisoning prairie dogs and has relied on sport hunting to keep their populations in check. Without this control a typical dog town on his ranch will expand about 20 acres per year. Multiply this by the number of dog towns scattered across any large ranch and the loss of income-producing grazing land becomes really serious.

“If prairie dogs are declared threatened I will lose my right to control them,” he told me, “so I will have no choice but to completely poison them out before the law goes into effect. My neighbors will be forced to do the same thing.”

I am not of vindictive spirit and admit without hesitation that I will continue reading National Geographic and Smithsonian, for they have much to offer. Charitably, I feel that the senior editors of these fine magazines were simply duped by a cabal of lesser lights with anti-hunting/fishing agendas. So we invite them, and all other mis- directed protectionists, to join outdoor life in educating the public to the fact that hunters are the best friends the prairie dog will ever have, and that recreational shooting is the only humane way to hold their numbers within acceptable limits while at the same time guaranteeing healthy, disease-free populations for future generations to enjoy.