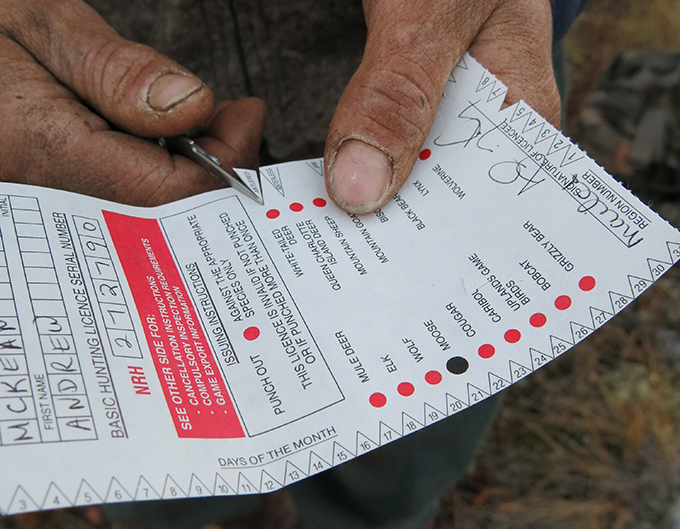

Last fall, I disappeared into the wilderness of British Columbia’s Spatsizi Plateau on a 10-day hunt for moose, mountain caribou, and grizzly bear. When I didn’t return as scheduled, my colleagues suspected things had either gone too well or not nearly well enough. As this journal from two weeks in the field reveals, both were the case.

Day 1: Flying In

As the twin-engine Cessna Grand Caravan tips into the headwaters of the Spatsizi River and follows its braided course downstream, I slip off my watch. I haven’t seen a road or a power line since we took off in Smithers, and time in this wild country appears to be marked by seasons, not minutes and hours.

We land on a hummocky airstrip beside a collection of hand-hewn cabins thrown up along the Spatsizi. It’s as though I’ve been tossed back in time. Hyland Post, as this settlement is called on maps, has been a fur-trading camp, an Indian mission, a post office, and a wilderness general store. Now it’s headquarters for Collingwood Brothers, one of the best-regarded big-game outfits in British Columbia. You can get here only by air, jet boat, or horse.

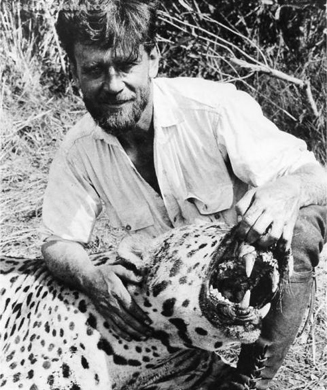

A group of weary and bewhiskered hunters is waiting on the plane, and it appears they’ve made good use of their 10 days here. The pilot loads moose racks larger than any I’ve seen, and caribou antlers that look like armfuls of hoe handles. Bloody canvas bags containing moose, caribou, and mountain goat go in, too, and on takeoff the meat-heavy Caravan groans as it lumbers above the spruce trees at the end of the runway.

Among the airfield introductions: Max Gauthier, a five-foot-five French Canadian in a herringbone Paddy cap, who will be my guide for the duration. As he helps me schlep my gear into a log cabin, I can’t help but smile at his thick Quebec accent. “Cabin” becomes “KAY-bean,” and he helpfully explains that his last name is pronounced “Go-TEE.” His thin beard, bright eyes, and springy step remind me of a leprechaun, but without any of the creepiness.

As he leaves me to settle in, Max asks a question I can’t possibly hear often enough: “Would you be ready to take a walk for a moose in an hour?”

I am, and we do. We climb a low ridge above camp, where the cook had seen a bull moose during the week. For two hours we hike and call, and Max takes two plywood paddles out of his backpack and holds them by his ears to make himself look like a pint-size bull. We are ready for moose. The moose don’t show. We return to camp in the dark.

Over dinner, outfitter Reg Collingwood asks another question I am happy to hear: Which of the three animals—moose, bear, or caribou—do I want to target first on my 10-day hunt. I stammer long enough that Reg decides for me. “Hunt for bear. That’s the tough one. If you’re lucky, you’ll find the others while you’re looking.”

Then Reg looks across the table at Max and says one cryptic word: “Dawson.”

Day 2: Dawson River

I’m aboard Amos, a salt-and-pepper gelding who moves so slowly that the 14 miles to Dawson River’s spike camp might be tedious if not for the spectacular scenery. I ride between Max and Tania Millen, our double-tough wrangler, as we enter a broad, well-watered valley. Willow stands and blueberry bogs rise to scattered spruce that give way to stunted fir and low-slung shrubs before topping out on broad, grassy plateaus dusted with snow.

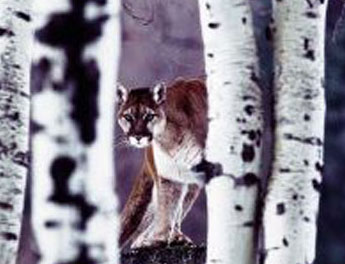

Max notices my gaze, and we stop while he deconstructs the country. We’ll look for moose both in the low willows and the high spruce. The caribou are on top of the plateaus, and when we go after them, we’ll probably take backpacking food and a tiny tent and stay up there for several days. Bears, says Max, could be anywhere.

At the spike camp, we unfurl a canvas wall tent that’s been stashed in trees, fit together pieces of a sheet-metal wood stove, and fill a backcountry pantry with the food we unload from the horse panniers. It’s late afternoon by the time we finish, but the October sun is bright and warm, and Max suggests we cast out to glass for bears. We’ve ridden maybe 4 miles from camp when I spot something white below the trail. It’s moose antlers, half-hidden in the hemlock. Max ties our horses to bunching blueberry while I sneak to a vantage point.

It’s a nice bull, wide but not overly palmated. Max slides in beside me and raises his binocular. “Good bull,” he says, and something about the way he says it makes me settle the Savage rifle on my pack and find the bull in my scope. “I think we should take him,” whispers Max. So I do, delivering two 180-grain Federal Trophy Copper slugs just behind his shoulder.

Just like that, I’m done moose hunting. We take pictures and then take apart the bull, both of us watching nervously in the gray twilight for a grizzly bear to charge in and claim the fresh meat. It’s too late to fetch the pack stock, so we lay the quarters across brush to cool in the night air and stuff warm, bloody 50-pound backstraps and tenderloins in our hunting packs.

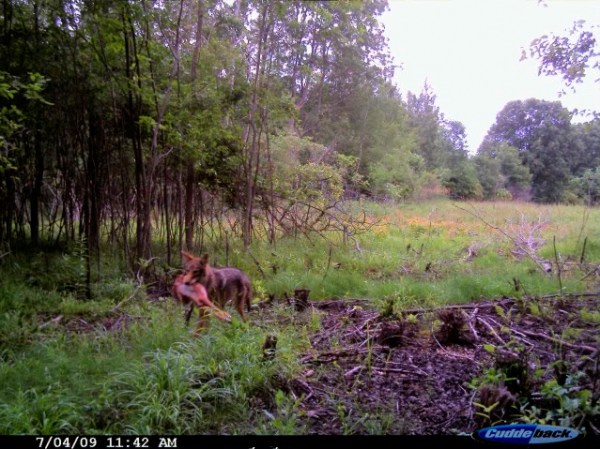

The trail back to camp is a thread of black just perceptibly blacker than the night. I give Amos his head and he plods the course. After an hour of riding, branches slapping my face and howling wolves flanking us, we see a pool of flickering firelight in a clearing, the timeless welcome for a returning hunter.

Day 3: Making Meat

We wait for light before returning to the bull, mainly so we can avoid being ambushed by bears that might be feasting on the carcass. Thankfully, only ravens have pecked at the ribs. We work until the afternoon, packing meat into panniers, and send Tania back to Hyland Post with horses loaded with moose.

We have time to make a foray to a berry patch Max says grizzlies sometimes frequent. We are nearly to the spot when the horses stop in the trail, stamp their hooves, and throw back their ears. A huge caramel-brown bear is on the trail in front of us, and as I vault from Amos and strip my .300 Win. Mag. out of the scabbard, it streaks through the willows. I have no shot, but the encounter fills me with adrenaline and hope.

Day 4: Encounter with a Griz

We rise before light and return to the berries. Something is different in Max’s laid-back attitude. He’s impatient. Today, we are not casting about blindly; we’re hunting not only a specific animal, but the apex predator of this immense wilderness.

I double-check my gear: shells, the pull-up turrets of my Weaver scope, and my rangefinder. We tie the horses and climb a knob. I cannot believe what we see in the berries: the same brown bear grubbing in the willows. He’s a ways out—180 yards—but the wind is in our face. We have time.

I watch that bear in my scope for a couple of chilly hours. Can it be this easy, I wonder? Two remarkable animals in as many days? At this rate I’ll have time to catch up on my reading and sleep. Finally, the bear sits on his rump, facing us. It’s not a perfect shot—he’s turned slightly away, with a few willow branches around his torso—but Max likes the presentation and I slide the Savage’s safety off.

The shot feels great, and in the recoiling scope, I see the bear drop into the willows. We don’t see movement, but we don’t hear a death bawl either. We wait a full hour and then slowly, nervously walk into the head-high brush. I’m ashamed to admit how relieved I am when Max volunteers to go first. We get to the spot where the bear had been sitting. Nothing. No bear. No blood.

We are puzzled and frankly shocked, but we cast out from the epicenter, each of us scouring the ground and leaves for blood, ears tuned to the sound of a charging boar, our rifles unslung and our stomachs in our throats. We find squashed berries but no sign of a hit. So we widen our search, spending hours nervously inspecting every square inch for sign. Then we expand the search still farther, walking every game trail in the willows. We search for five straight hours before Max suggests retrieving the horses.

“We can get a different vantage from the saddle,” he reasons. We lead the horses into the willows, their eyes wild and their nostrils flaring with the rank smell of bear. I swing astride Amos just as Max tosses me my backpack. All of a sudden the world explodes. Amos is bucking and throwing his head. I’m waving around my pack, trying to keep my balance. Then Amos unleashes a giant, eruptive buck and I fly off, turning at least once in the air and landing in a patch of willows. My backpack lands on my chest with an unceremonious thump.

I stagger up, work the creaks out of my body, and look over at Max. He’s worried, but when he sees I’m okay he starts giggling.

“Amos, he thinks your backpack is dat bear.”

I’m not quite ready to laugh, but we need the comic relief to break the tension. It’s starting to settle in that I missed this bear. We search from horseback until we lose light.

Day 5: No Bear

We spend all day looking for sign of the bear as the weather closes in and a cold rain turns to snow. On the way back to camp I check the zero on my rifle, aiming at a shed moose antler marked with a black X of electrical tape. My rifle is shooting 6 inches to the left at 100 yards. My scope must have gotten knocked off plumb as I slid it in and out of scabbards and rode through brush.

Day 6: Snow Day

Snowed in all day. Tania trails back from Hyland to our snowbound camp with some bad news: Word from headquarters is that a big winter storm is on the way. We play cards and tell stories inside the canvas tent, the wind rising outside. I’m still aching, both physically and psychically, from my griz incident.

Days 7–8: Through the Clouds

We decided last night to make a play for caribou on top of the plateau. The three of us ride into a cold, stabbing rain, but as we climb higher through the spruce, the snow returns. Finally we ride above the weather, into a blindingly bright world of snow and rocks on top of the Spatsizi Plateau. This is caribou country, treeless and barren. We work the edges of the plateau, glassing pockets where caribou might get out of the biting wind. We find a small herd, but the only bull is young. We push the horses miles through drifted snow but fail to cut any caribou tracks. We huddle up in a cut and have a conference. We could stay up on the plateau overnight. Or we could return to camp and trail down to Hyland tomorrow. We opt for the latter, and pull into the post the next day drenched and dejected.

Day 9: River Running

I’m in a jet boat, roaring up the Spatsizi, Reg Collingwood at the helm. With the weather still socking in the high country, we’ll boat 30 miles to a wall-tent camp and check berry patches along the way. With two days to hunt, I’m feeling the pressure.

Day 10: Big-Game Paradise

Reg and I glass hunter-killed moose carcasses along the river. It’s illegal to shoot a bear off bait in B.C., but if we see one maybe we can get a shot as it leaves the carrion. No luck. We cut fresh tracks on sandbars, but don’t see a single bear.

As we eat lunch on a gravel bar, the clouds break and I glass the plateau above the river. There’s a herd of caribou maybe 4 miles away, but I can clearly see an immense bull pushing cows. Reg looks at the weak sun and decides we don’t have either the time or the weather to go. Better stay on the river and hope for a last-minute griz.

Later in the day, as we glass a slope for bears, I look up the mountain. China-white mountain goats cling to the shale. A herd of Stone’s sheep grazes and loafs on a grassy shelf. A bull moose tends a cow in a bog at the base of the mountain, and in the mud along the river I see wolf and grizzly bear tracks. I spy a lone caribou in a snowfield just below the clouds. This is big-game paradise.

Day 11: Grounded

I packed my bags with a heavy heart last night. I have a remarkable moose—we taped his spread at 60 inches— but I’m not ready to leave the Spatsizi. At breakfast, the camp’s two-way radio crackles. Today’s flight has been scrubbed due to deteriorating weather. My heart soars. Reg fires up the jet boat.

Days 12–13: Stranded

No bears yesterday or the day before, and today’s flight is cancelled. If I can’t leave by air tomorrow, I have a choice, Reg says. I can charter a plane for $3,600, boat out with him, or ride out with Max and the pack string. But if I stay here, I won’t see another human until next May.

The boat ride is a five-hour scream through whitewater and hull-wrecking canyons. The two-day horseback trail stretches over 85 miles.

Day 14: Back to Smithers

I opt for the horses, if only to see more of this remarkable country. But it turns out I don’t have to saddle up. The weather breaks and I catch the last plane of the season. As the Cessna climbs out of camp, I spy caribou on the plateau. There’s a very good bull in the herd, and I swear he looks up as we fly over.