Hunters and anglers hang their hats on a lot of long-accepted truisms, some of them generations old. But just how true are they? Stop speculating. Outdoor Life has the definitive answers.

1) Which Broadhead Style Penetrates Best?

By: Todd Kuhn

A lot of hyperbole has been written about broadheads over the years. We’ve been schooled on their ability to withstand explosive assaults on plywood and car tires. We’ve seen the high-speed film of various heads blowing through steel drums. And while this makes for entertaining reading and thrilling footage, it gives us little quantitative data on a broadhead’s real-world penetration performance on game.

Passing Through

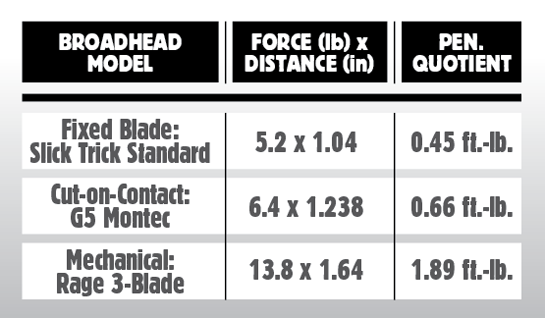

A broadhead’s ability to pass through an animal is directly related to its frontal profile, blade angle (including deployment angle on mechanicals), cutting diameter, sharpness, and the amount of kinetic energy the broadhead and arrow shaft carry at the moment of impact. Penetration is particularly critical 1) at longer shot distances; 2) when the arrow strikes obliquely; 3) when using lower draw weights; and 4) when pursuing game larger than whitetails.

The laws of physics dictate the amount of “work” an arrow has to do to penetrate a target animal (expressed in foot-pounds, inch-pounds, or joules). This work (W) is equal to the force (F) required to penetrate multiplied by the distance (D) over which that force must be exerted (W=FxD). The kinetic energy an arrow carries (as provided by the bow) is what affords it the ability to perform this work. When that’s depleted, the arrow’s forward movement stops.

Of course, the amount of drag, both cutting (via the broadhead) and sliding (via the arrow shaft), varies as the arrow penetrates the hide, hair, muscle, tendon, and bone. But generally speaking, if two broadheads impact with the same amount of kinetic energy, and Broadhead A exhibits half the drag of Broadhead B while penetrating the target, then Broadhead A will penetrate twice as far.

A Penetration Measure Is Born

We set out to devise a simple, straightforward test for evaluating a broadhead’s ability to pass through an animal. We wanted a test that would be consistent for each boradhead design, and could be easily duplicated.

To this end, we selected a homogeneous test medium (a U.S. Postal Service Express Mail box placed on a certified electronic scale) and measured the force in pounds that was required to pass each broadhead through the medium. Next, we measured the overall length of the broadhead from its tip to the point at which it completed its penetration through the test medium. This length served as the “distance” in the work formula. We then multiplied F by D for each, resulting in inch-pound measurements that were subsequently converted into foot-pounds. This measure in foot-pounds, which we dubbed the “Penetration Quotient,” provides a data point that is proportional to the penetration force for each broadhead to penetrate an arbitrary medium.

The Field And Results

We tested 18 popular broadheads, including six each of three different styles: cut-on-contact, fixed-blade, and mechanicals. For each head, we repeated the penetration test 10 times. The standard deviation of the measurements on each head was approximately 0.05 foot-pounds, revealing that despite being relatively rudimentary, the test is remarkably precise.

The results were striking to say the least. First, there was no statistically significant difference between the cut-on-contact and the fixed-bladed broadheads. Second, the mechanical broadheads required approximately three times the penetration force of the other two designs (with rear-deploying mechanicals holding a slight advantage over front-deploying ones).

While the distinct advantage of mechanicals is their ability to fly true no matter the compound’s tune and the speed at which they’re shot, they are at a disadvantage in energy use. However, with modern bows producing dizzying amounts of kinetic energy, this energy loss may now be moot.

Fixed-bladed broadheads, on the other hand, have traditionally had difficulty flying true, and their launch from the bow is critical to their flight. However, today’s compounds are capable of amazingly precise launches, and thus are capable of pushing fixed-blades with uncanny precision.

2) Picking the Top Hunting Breeds

By: Brian Lynn

The argument over which breed of dog is the best hunter has probably raged since canis familiaris was domesticated 33,000 years ago. But since we’ve selectively bred modern dogs to perform specific tasks, the case for top dog is impossible to settle unless you choose from the various breeds within similar groups.

To put a little objectivity into this most subjective of topics, we have to look at breed-specific performance in field trials and hunt tests. Established standards that gauge a dog’s ability to perform relevant tasks at high, consistent levels mean the dominating dogs possess something that others don’t. It could be prey drive, a willingness to please a human, rate of maturation, a superior nose, or overall intelligence that allows them to perform consistently better than other dogs bred to perform the same task.

Additionally, the aptitude to proficiently hunt multiple species adds value to a dog, and its overall health can save you thousands in vet bills.

Retrievers: Labrador Retriever

Stats: Won 55 Amateur Field Champion titles, 62 Field Champion titles, and 1 National Amateur Field Champion title in American Kennel Club field trials in 2012. Chesapeake Bay retrievers and golden retrievers accounted for a combined 4 AFC titles and 1 NAFC title.

X Factor: Intelligent, willing to please, and quick to mature, Labs can handle training on advanced concepts at an early age.

Utility: Ducks, geese, pheasants, quail, chukar, grouse; family dog.

Genetic disorders: According to Paw Print Genetics, Labs suffer from at least 16 genetic mutations that should be screened for prior to breeding.

Hounds: Treeing Walker

Stats: Treeing Walkers account for 20 of the last 25 coonhound United Kennel Club World Nite Hunt Champions.

X Factor: A treeing Walker’s hot nose and speed give it an advantage in competition. Additionally, its prey drive, intelligence, and desire to range deep serve it well in hunting circles, as well as competition.

Utility: Raccoons, deer, squirrels, cougars, bears.

Genetic disorders: Relatively new (they were granted AKC registration in 1945), Walkers descend from English and American foxhounds, as well as an unknown dog. As such, no genetic mutations or overt health concerns have been identified.

Spaniels: English Springer

Stats: In 2012, there were 37 AFC titles, 28 FC titles, 1 NAFC title, and 1 NFC title won. Cocker spaniels didn’t break into double digits in any category.

X Factor: Thanks to dedicated breeders, a field line of springers still exists despite their popularity in the show ring. Birdy dogs willing to please, springers can handle the training necessary to pull double duty on both upland birds and waterfowl alike.

Utility: Pheasants, quail, ducks.

Genetic disorders: Dating to 1800, springers have a handful of genetic disorders. Paw Print Genetics cites six mutations to screen for.

Pointers: English Pointer

Stat: Until last year, they won the AKC National Championship for Field Trialing Bird Dogs at Ames Plantation for 43 years in a row.

X Factor: With the highest prey drive of any bird dog, English pointers have an extra gear they use on the hunt. All-age dogs run big in search of birds and will go through anything to find them.

Utility: Quail, grouse, pheasants, chukar.

Genetic disorders: An anomaly in the dog world, the English pointer is one of the older breeds but doesn’t have any serious disorders to worry about beyond standard health issues.

Curs/Feists: Mountain Cur

Stats: In the relatively new world of UKC competitive squirrel hunting, mountain curs have won better than 80 percent of top-finishing places. Treeing curs (a first-generation cross of coonhounds and mountain curs) account for the remainder of placements.

X Factor: They have an excellent nose and speed, and trailing, treeing, chase, and bark instincts.

Utility: Squirrels, raccoons, bears, hogs; all-purpose farm and guard dog.

Genetic disorders: A less-than-standard breeding program has introduced multiple breeds into mountain curs, a relatively new breed. As such, no known breed-specific genetic issues exist.

3) Can Deer Smell Your Pee?

By: Tony Hansen

Dean Gericke is a details guy. He’s methodical, meticulous, and everything you’d expect a top-notch engineer to be. He’s also a pretty darned good deer hunter. My question to him was simple: Do you pee from your treestand when you’re hunting?

“No. Never. Ever. I go out of my way to be as scent-free as possible when I’m hunting,” said Gericke. “I feel that I jeopardize that strategy if I introduce any other scents that are foreign to the deer woods. Human urine is foreign.”

When I responded that there is evidence to suggest that human urine and deer urine are almost identical from a chemical standpoint, well, he got a little pissy.

“I don’t care. When I eat asparagus, I can smell it when I pee,” he said. “If I can smell it, a deer can smell it.”

As one who is fairly fanatical about “doing things right” in the woods, I admit to being on the fence about this whole urine issue. Some, like Gericke, feel pee’s place is in a toilet, not below your stand. Others say you should not only pee freely, but that doing so is beneficial and can attract deer.

Believe it or not, there has been a fair amount of research conducted on this subject. A University of Georgia study, for example, indicates that there is nothing in human urine–from a chemical standpoint–that should alarm deer.

I have always operated under the theory that pee is pee. In an effort to test that theory, I called in a favor and managed to have two urine samples smuggled into a “facility.” One could speculate that this facility is used for urinalysis in the medical field. I can neither confirm nor deny such speculation.

The Verdict

The results were, well, pretty boring. My pee is yellow. A deer’s pee is yellow. Both were negative for glucose, ketone, and blood (whew!). The deer’s urine did have trace amounts of leukocyte esterase and nitrite, but aside from this indicating that the deer may have a urinary tract infection, there was virtually no difference in the test results.

Admittedly, this wasn’t an in-depth chemical analysis. But can human pee and deer pee truly be that different?

Well, that’s where things get tricky. What you eat can have a major impact on the smell of your urine. In fact, it may not be the urine itself that’s cause for concern, but the odors caused by the byproducts that the urine contains. So, unless your diet mimics that of a whitetail, odds are good that your urine doesn’t smell quite right. I know I’ll be hauling a pee bottle to the stand with me this fall.

4) Determining the Ideal Treestand Height

By: Todd Kuhn

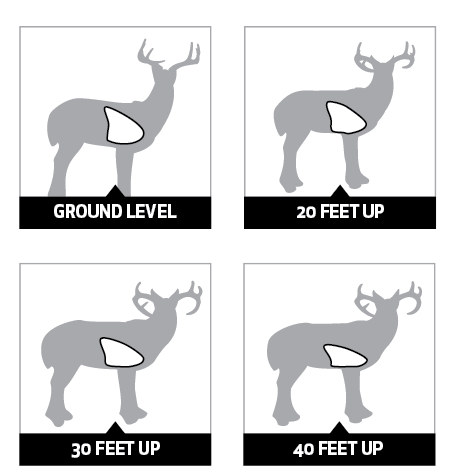

For some, climbing nosebleed high somehow qualifies them for a hunting merit badge. But does it earn them more shot opportunities? As anyone who has ever hung a hang-on knows, there are many factors to consider when settling in at the “perfect” hunting height.

Let’s Get Physical

Conventional wisdom says that the higher you climb, the less detectable your scent will be. Well, in fact, the higher you climb, the larger your scent plume and the greater its dispersion. Given a deer’s ability to detect minute levels of human odor (some whitetail biologists estimate approximately 10 parts per 1,000,000), then the higher you climb, the more you broadcast scent.

The Pythagorean theorem states a2+b2=c2,so the higher you climb, the greater the diagonal distance to your target below. For instance, if you’re up 40 feet and 60 feet away, then the actual distance to that target is 72 feet.

As the diagonal distance increases, the physical kill zone becomes smaller. The target size shrinks in both depth and height. In layman’s terms, the higher you climb, the more likely you’ll miss a diminishing target. Additionally, as your climbing height increases, your ability to visually resolve already diminutive target features (e.g., the kill zone) decreases as the distance to the target increases.

So What Height Is Perfect?

Rest assured, no one hunting height fits all. However, mathematically speaking, the best hunting height range is between 15 and 18 feet. In this range, the increased diagonal distance minimally affects target distance and size, and visual resolution is all but unaffected. However, when hunting at these heights, you must be hyper-cognizant of your movement, and by all means play the wind to your advantage.

5) Which Fishing Knot is the Strongest?

By: Bob McNally

After extensive testing at IGFA headquarters in Dania, Fla., we’ve arrived at three knots that will serve anglers well wherever they fish. All knots were tied dry and tested three times each on the device used to verify line tests for potential IGFA-record fish.

1. Best Line-to-Hook/Lure Knot: Eye-Crosser

With 20-pound-test Berkley Fireline Crystal, the knot broke at 30.4 pounds, 152 percent above the line’s break rate.

2. Best Line-Line Knot: Double Uni-Knot

With 20-pound-test Stren Super Braid connected to 25-pound-test Seaguar InvizX fluorocarbon, the fluoro broke at 29.24 pounds (117 percent).

3. Best Loop Knot: Homer Rhode

With 20-pound-test Berkley Vanish fluorocarbon, the knot held flawlessly, with the line breaking above the knot at 23 pounds (115 percent).

6) What Is the Toughest Game Animal?

By: Andrew McKean

Wherever hunters gather around a campfire, sooner or later the conversation turns to the toughest game animals. It’s a way of honoring our prey, and of provoking each other.

Leading candidates in this category include the surly Cape buffalo, old mossback mule deer, hippos, crocs, coyotes, and even high-country chukar partridge. They’re all wrong. The toughest animal to bring down is the common Canada goose.

For the past five years I’ve kept a detailed journal of my hunting activities–places, species, partners, guns and loads, weather conditions. All those details go into my little red-bound book. I’ve done a fair job of noting the number and distances of shots required to kill my quarry, and this book confirms I’m a pretty good shot on game.

But geese stand out as being especially difficult to kill cleanly. Over these past five years, I’ve shot something more than 300 shells at honkers. I’ve retrieved only 47 of these birds. That’s a pitifully low kill percentage, but it gets worse. I’ve hit several dozen that showed evidence of carrying pellets, but that I wasn’t able to retrieve. Either they sailed out of retrieval range or they didn’t go down at all, but rather absorbed the pellets, lost a few feathers, and flew on.

Part of my problem is range estimation. Geese are generally flying higher and faster than I think they are, and I routinely misjudge the correct lead. Too, a goose’s vitals area is pretty small compared to its overall body size, and it takes a couple of pellets in just the right place–the head or neck–to kill it immediately. Lastly, by the time I get serious about goose hunting, it’s late in the season and the birds are heavily plumed and extremely wary. Those dense feathers and thick layers of fat are hard to penetrate, especially with steel pellets that strike from long distances.

My data collection isn’t comforting, but it is educational. Since I’ve crunched these numbers, I’ve become a more restrained, lethal goose hunter. In the past year, I’ve waited for birds to come into range, I’ve become a better caller and decoyer, and I’ve declined to take shots at the end of my effective range. If I can keep boosting my killing percentage, I might reassess my conclusion that geese are our toughest critters. But as adaptable as geese are, they’ll probably keep finding ways to stay alive.

7) What Kills the Most Hunters?

By Tony Hansen

Hunting is an exceptionally safe activity. It’s safer even than, say, bowling, in which one injury occurs for every 1,607 participants, compared to one injury per 2,000 participants in a firearms deer season (statistics taken from a 2010 National Shooting Sports Foundation study).

“Safe” is not quite the same thing as “danger-free,” however, so let’s take a quick quiz. What do you think would be the most likely cause of death while hunting? A fall from a treestand? A slip while climbing a mountain? A self-inflicted gunshot wound? Being shot by another hunter? Exposure? All of these responses are likely wrong.

“Concrete numbers are very difficult to get, but we’ve determined that roughly 12 people in Michigan die each year from heart-related issues while hunting,” says Dr. Susan Haapaniemi, exercise physiologist for preventative cardiology and rehabilitation at William Beaumont Hospital in West Bloomfield, Mich.

How does that compare to hunting-related deaths from treestand falls and shooting accidents? In the past three years combined, there have been eight “hunting-related” fatalities in Michigan, and all were the result of gunshot wounds.

“I feel very strongly that hunters should pay just as much attention to the health of their heart as they should to gun safety,” says Haapaniemi. And she has the numbers that show why.

In a study published in the American Journal of Cardiology, Haapaniemi and a team from Beaumont Hospital fitted 25 hunters with heart monitors and tracked their heart rates while they were hunting. Of the 25 participants, 17 had established coronary heart disease, while the rest had common risk factors (overweight, smoking, high blood pressure, or high cholesterol).

The results were, well, heart-stopping.

“Maintaining your heart rate at 60 to 80 percent of its maximum rate for a short period of time is generally recommended as part of a strenuous exercise program. The more fit you are, the longer you can safely sustain a higher percentage,” says Haapaniemi. “What we saw in the study went well beyond those recommendations. Of the 25 hunters in the study, 21 of them reported heart rates above 85 percent of their maximum rates. Several were above 100 percent for a sustained period of time.”

What’s most interesting is the factors that caused these sudden spikes in heart rate.

“Just seeing a deer–not shooting at one, but simply seeing one–caused heart rates to double in some subjects,” Haapaniemi says. “Getting a shot would increase the rate even more. Then there would be a slight decline. But when they started to track the deer, it would spike again.”

When it came time to gut and drag the deer, that’s when things got scary.

“The act of gutting and dragging the deer, without question, is dangerous for anyone with any type of risk factor for heart disease or for anyone diagnosed with a heart condition,” Haapaniemi says. “It’s strenuous exercise. There is adrenaline involved. Excitement. Anticipation. Whatever the combination, it very clearly had a significant impact on heart rates.”

Her advice is simple: “Do not gut or drag a deer [on your own],” she says. “The act of dragging a deer is where we saw rates well above 100 percent of the recommended rate for sustained periods. That’s a heart attack in the making.”

8) Do Bow Vibration Dampeners Work?

By: Todd Kuhn

Sometime in the late 1990s, “vibration” became the buzzword in the archery industry. Bows suddenly became “vibration- and shock-free” and “whisper-quiet.” Physics dictates that bows cannot be devoid of noise and vibration, as these are the results of launching an arrow. But do add-on dampeners reduce noise and vibration by “up to 65 percent,” as one manufacturer has advertised?

To measure vibration, we attached two 25g accelerometers to the riser of a McPherson Monster and fired a 400-grain carbon arrow with it 10 times without any vibration-reduction devices, and then 10 times each in four different configurations with different amounts of dampening devices. A Vernier Sound Level Meter recorded noise.

Bare Bow: With this setup, we measured a mean vibration of 7.596 m/s2. Shot noise was 93 dBA.

Bow + Riser Dampeners: With the riser dampeners replaced, we measured the shot vibration at 7.64 m/s2, an increase of 0.60 percent. Shot noise remained at 93 dBA.

**

Bow + Riser Dampeners + Aftermarket Rubber Dampeners:** We added a pair of popular rubber-mounted limb vibration dampeners. We recorded a mean shot vibration of 7.483 m/s2, a decrease in vibration from the bare bow of 1.49 percent. Shot noise was measured at 92.9 dBA, a noise reduction of 0.11 percent.

Bow + Riser Dampeners + Aftermarket Rubber Dampeners + Second Set of Rubber Dampeners: A second set of dampeners (from another brand) was then added. A mean vibration of 7.213 m/s2 was recorded. This represented a reduction of 5.04 percent from the bare bow. A shot noise of 92 dBA was a reduction of 1.08 percent.

Bow + Riser Dampeners + Rubber Dampeners + Second Set of Dampeners + Stabilizer: With an aftermarket vibration-dampening stabilizer added, we recorded a mean vibration of 7.412 m/s2. This represented a decrease in vibration of 2.42 percent over the bare bow, but an increase in vibration over the previous setup of 2.76 percent. Shot noise registered was 92.9 dBA, an increase of 0.98 percent over the previous setup.

9) Does Reloading Save You Money?

By: John M. Taylor

There are four reasons to reload: Pride in shooting ammunition you have crafted, improving accuracy in a particular rifle or handgun, preparing a load that is not commercially offered, and saving money. Tweaking a rifle load by as little as a grain or two of powder can tighten a group to one-hole accuracy. The clay shooter can cut his ammo costs by half when he shoots the 28-gauge or .410, as can the over-the-course or 3-Gun competitor.

The basic loaders are the single station that produces completed rounds one at a time. A competitive shooter will opt for a progressive tool that, although more expensive, will kick out a completed round with every cycle of the machine–a home ammo factory, if you will. Along with tooling, any reloader needs several accessories. RCBS offers kits like the Rock Chucker Supreme Master Reloading Kit ($473), which includes a Rock Chucker single-stage press, a powder scale, a powder measurer, a chamfer and deburring tool, case lube, a case-lube pad, case-neck brushes, a powder funnel, and a Speer Reloading Manual. In all cases, caliber-specific dies are not included. To move up to a progressive machine, such as the Dillon Rl 550 B, excpet to spend $500 to $600. In addition, rifle and pistol reloaders will need a case cleaner, a trimmer, and other accessories.

Shotshell reloaders have the same choice of single-stage or progressive. A hunter might for a single-stage tool like the MEC 600 Jr. Mark 5, which will run about $200. A target shooter might opt for a progressive loaded. Plan to spend $600 for a MEC 9000, $1,200 for the RCBS Grand or Dillon, or about $1,500 for a top-of-the-line Spolar. You can also add hydraulic or electric operation for about $500 more.

10) Which Rifle Action Is More Reliable?

By: Bryce Towsley

In “Gun Guy” circles, some things are just taken as fact. However, if half a century of messing with guns has taught me anything, it’s that the “facts” are not always right.

For example, take the concept that a controlled-round-feed rifle is less prone to jamming than a push-feed. Everybody knows a CRF gun will never jam, while using a PF rifle is just asking for trouble, right? And this is especially true if you have to shoot from any position other than with the top of the gun facing the sky.

I must say that in many years of hunting, the only time I jammed a rifle at a critical time was with a push feed, and I did it as a very angry bull moose was attempting to stomp me into the bog. Another guy with a .375 had to settle the matter, and my gun was out of commission until we got it back to the toolbox in the truck. But, in the interest of full disclosure, that rifle was a POS that had never worked right.

The “experts” tell us that we should only use a controlled-round-feed gun for dangerous game. I have used one for elephant and Cape buffalo. The buffalo was a one-shot kill, but the elephant hunt got pretty “African,” with a lot of shots fired.

That said, I have used push-feed guns to take three other buffalo, a leopard, a brown bear, and a hippo. A couple of them got noisy as well, but I did not experience any problems with any of these rifles. Of course, unlike with the moose hunt, I tested those guns extensively before heading out for the hunts.

Still, the question remained unanswered. So, I picked four rifles out of the vault: two PFs (a Remington Model 700 in .375 H&H and a Winchester Model 70 in .30/06) and two CRFs (a Ruger M77 Hawkeye in .416 Ruger and a Mauser-action Pasadena Arms in 6mm Remington), one of each in a dangerous-game cartridge and one of each in a deer cartridge.

The Methodology

I ran a full magazine (three rounds in the magnums, four in the standard guns) through each gun in four different positions: holding the gun as you would when shooting normally, then turning it 90 degrees on its side, upside down, and then on the other side. I ran the actions at “hunting speed”–not slow, but not in panic mode either.

There was only a problem with one rifle while running it upside down. “See I told you!” I can hear all the experts saying. “Push-feed rifles are trouble!”

The thing is, the troublesome rifle was not a push feed. Both of the PF rifles ran fine in all positions. However, the CRF 6mm twice popped a cartridge out of the magazine without engaging the extractor. Both times the cartridge slid into the chamber ahead of the bolt, but the extractor would not pass over the rim so I couldn’t close the bolt. It jammed the gun and I had to get a cleaning rod to remove the stuck cartridge, so a field fix would not have been possible.

I would not relish the idea of stopping a buffalo charge with a CRF 6mm, particularly while holding it upside down. Does this test settle the question? Probably not. But it makes me feel a lot better about push-feed actions, and a little less trusting of the “experts.”

11) Which Bullet is Best for Small Game?

By: Ellis McKean

You already know that all .22 long rifle bullets are not created equal. But you may not realize that the best bullets for small-game hunting are the slowest–and often the cheapest–loads on your gun store shelves.

To determine which type of bullet penetrates the deepest and retains the most of its unfired weight, we conducted a test with four popular .22LR loads: round-nose CCI Subsonic (40 grains) and CCI Blazer (40 grains), and hollowpoint Winchester Varmint HE (37 grains) and CCI Stinger (32 grains). The Stinger, at 1,640 fps, and the HE, at 1,435 fps, are both billed as high-velocity loads. The Blazer’s published muzzle velocity is 1,235 fps, and the Subsonic’s is 1,050 fps.

We weighed all the bullets on a powder scale and recorded their unfired weight. Then we shot them into gelatin blocks at 20 yards. We collected the largest fragments, and compared the weights of unfired and fired bullets.

We found that the two round-nose bullets retained 23.5 percent more weight than the hollowpoints. Individually, the CCI Subsonic retained 99 percent of its weight, the greatest amount of retention, while the Stinger retained the least–66 percent.

We also measured penetration. Surprisingly, the slower, more retentive bullets penetrated deepest into the gelatin. The Blazer penetrated 17.9 inches, the farthest by 6.5 inches. The Stinger penetrated only 8.4 inches into the gelatin, the shortest distance of the four.

The hollowpoint, high-velocity loads definitely have a place in shooting sports, but small-game hunting isn’t one of them. If you’re interested in good penetration and consistent bullet retention, stick with a slower hollowpoint.

12) Which Cartridge Is King?

By: John B. Snow

Any hunter who says there’s no difference between the .30/06 and the .270 has less spine and sense than a jellyfish. Here’s why.

Versatility: If you were forced to choose one or the other to use for the rest of your life, only a fool would go with the .270. The .30/06 comes in more configurations–hunting, target, military surplus–and a greater span of bullet weights and styles. It is more common and easier to find.

Trajectory: Compare popular flat-shooting loads using the same style bullet–a 130-grain for the .270 and a 150-grain in the .30/06. At 400 yards, the .270 drops 24.6 inches, compared to the .30/06’s 27.3 inches. I’d call that a draw, though we’ll give it to the .270 on pity points.

Killing Power: You need to take down a large, toothy critter. In .30/06, you can use a 220-grain projectile–or go with a 150-grain in .270. If you want to live, the .30/06 is the only choice.

History: The ’06 kicked the Nazis in their collective arsch, defeated the Japanese in the Pacific, and was used by our Devil Dogs in the Belleau Wood during the Great War. The .270? Please.

Edge: It’s no contest. The .30/06 is the superior cartridge, and that’s why it always has been–and always will be–the king.

13) Does Catch-and-Release Affect Catch Rates?

By: Dr. Hal Schramm

Though catch-and-release fishing has improved and even saved some fisheries across the country, it also seems to be having an unforeseen negative consequence on fishing success. Early studies documented higher catch rates in stretches of streams with catch-and-release regulations. For example, angler catch rates were 35 percent greater in Wisconsin streams with catch-and-release regulations than those with normal harvest regulations. In the Yellowstone River, individual cutthroat trout were recaptured more than nine times in a catch-and-release stretch of water.

Despite these and other success stories that support the intuitive axiom that such regulations result in more fish, two recent investigations seem to indicate that releasing trout does not necessarily mean that the fish will go on to fight another day. In fact, many may never be seen again.

TIn a 2006 British Columbia study fly anglers there fished four different 5- to 16-acre lakes only six hours per month. Despite immediate release of all rainbows, the catch rate declined 66 percent over the four-month fishing season. In the same study, a 3-acre lake was fished daily for eight hoursper day. Even though all rainbows were released, the catch rate declined from 16 fish per day during the first five days to five fish per day after 15 days.

Then there’s the study of trophy brown trout in New Zealand. Teams of fly anglers took to the reaches of a heavily fished river (the Owen River) and an isolated, lightly fished river (the Ugly River) on monthly three-day outings. Although trout densities were similar in both rivers, the number of trout caught per mile of river was five times greater in the Ugly than in the Owen. This difference is exactly what would be expected when comparing heavily and lightly fished waters, but there was a twist. While the number of fish caught was consistently low on all three days of each excursion on the Owen, the number of fish caught decreased on each successive day of each excursion on the Ugly.

Both studies attributed the low or declining catch rates to learning. It makes sense that caught fish may learn to avoid fake flies, but the decline in catch rates in the lightly fished lakes and the Ugly River, where only small portions of the population were caught, suggests other yet unknown factors are in play.

Two empirical, yet no less fascinating, studies on other species–one from Upstate New York and another from Buras, Louisiana–seem to support the research on trout. In an effort to gauge growth and mortality rates of bass, crappies, bluegills, and pickerel in a private lake in Sullivan County, N.Y., Outdoor Life deputy editor Gerry Bethge spent an August weekend in 2007 tagging upwards of 45 fish. Fish species and sizes were carefully recorded, along with tag numbers. Since then, no tags have been retrieved from catches in the 15-acre, moderately fished pond.

In Buras, Louisiana, redfish guides Joe DiMarco and Todd TK reported catching and tagging 1,500 bull reds over the past two years. The veteran guides were confident as to the fish’s survivability. Although the pair, along with other guides in the area, fish these same waters on a regular basis, no one has yet to catch a tagged redfish.

Although these observations may raise more questions than they answer, it seems difficult to maintain that catch-and-release practices have no impact upon a fish’s ability to avoid a hook.

14) Can an Ugly Stik Be Broken?

By: Gerry Bethge

“It’s like casting a wet piece of lasagna.”

“Trying to catch a fish with a boat anchor is easier.”

“Unbreakable? Bull.”

How the best-selling rod in history garners such little respect seems a mystery. Hundreds of thousands of Shakespeare Ugly Stiks have been sold in the U.S. since its introduction as the world’s first “unbreakable” fishing rod in 1976. Yet today, few anglers are willing to admit to ever having used one, let alone confess to having one on their boat.

So what’s so bad about fishing with an inexpensive rod that won’t break? Other than mediocre performance, not much–theoretically. Which is why we checked our collective fishing egos at the dock and put an all-new, soon-to-be-introduced two-piece Ugly Stik through its paces. Our goal was to break one.

With spinning reels loaded with 20-pound-test Berkley Trilene braid, we tightened down the drag and went after the abundant marsh redfish of southern Louisiana. The results? In three days of fishing, we cast 2,550 times, caught 38 fish weighing up to 17 pounds each, and yanked all but two of those over the gunwales of the bay boat without a net. We certainly abused the rod, but did not break it.

“I have fished them on everything from very nasty blue catfish in South Carolina to even nastier grouper and amberjacks over reefs and wrecks–and I couldn’t break one either,” says former Outdoor Life fishing editor Jerry Gibbs. “In the world of auto design, there’s the Ferrari F12 Berlinetta, and there’s the kind of muscle wagon you need for serious off-roading. Ugly Stiks fill the latter bill.”

15) Are Realistic Mouse Baits Better?

By: Gerry Bethge

Super-realistic modern fishing lures can fool fish, but can they dupe creatures with more discriminating palates and bigger brains? In what we came to think of as our most creative (read: foolhardy) test for this feature, we glued 10 hookless, mouse-imitating baits (as well as one real, dead field mouse) to a hunk of plywood in hopes of deceiving the laser-sharp vision of a raptor. We set our ingenious mousetrap in a rural field, positioned a trail camera nearby, and waited anxiously for the results.

Well, we got skunked–literally. After more than a month, the only critters to appear on our camera were a skunk, a fox, and a coyote–and none took the bait.

While this test was inconclusive, our other efforts revealed useful results.