I take a drink from my CamelBak, sucking down the cold water, then puffing it back up the tube and into the reservoir so it doesn’t freeze. The rest of the crew has stripped away their jackets to reveal a collection of wool sweaters and base layers. Lukas Leaf is reapplying sunblock, smearing the stuff across his cheeks and ears, and doing his best to avoid his beard. The sun has turned the snowy lake where we’ve stopped into one of those ridiculous tanning mirrors, bouncing rays from below into our eyes without relief.

A native Minnesotan with a taciturn disposition, Leaf speaks now, pulling out a map as his coworker Spencer Shaver and photographer Lee Kjos gather around. I step forward too, but my foot breaks the snow’s crust and I sink to the knee. My companions call this misstep “post-holing,” a term that had been new to me this morning. But I’m quickly becoming familiar with it.

Road to Nowhere

Our trail had begun at the edge of a frozen lake in Minnesota’s Superior National Forest and spit us out in the northern Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. To navigate canoe country in winter, we strapped on packs and, beneath those, chest harnesses attached to sleds, called pulks. At the trailhead, we crammed the pulks with everything from a wall tent and a wood stove to neon MSR snowshoes, two ice augers, and a bucket of live bait.

The snowpack on the portages alternates between sun-softened slush and icy chutes, and towing our gear uphill requires muscle and a pair of trekking poles for purchase. Shaver, 23 and sturdily built, seems to have no more difficulty dragging his sled than a Budweiser Clydesdale might. But the descents are trickier for all of us. The pulks pick up speed on the downhills, as I discovered when mine nearly knocked my feet out from under me. Eventually we learned to unbuckle the harnesses and hold them like leashes, letting the sleds bomb down first as we skated behind.

On the flats, I had a chance to look around. Ahead of me, Shaver would occasionally pause to collect scraps of peeling birch bark, pocketing the paper for tinder. Trees here are thick as bristles on a brush, and needles from jack pine and spruce litter the trail. Porcupine and rabbit tracks appear occasionally, and once, a bear’s. Deer, moose, and Canada lynx live here too, though are seldom seen. Some nights you can hear wolves, their howls echoing across the lakes. This is one of the only wildernesses in the Lower 48 where government shooters and trappers were unable to eradicate them in the early 1900s. But it’s quiet now, as if we’re the only ones out here.

“This last section was 142 rods,” Leaf is saying as I join them, running a finger along the canoe portage we just completed. One rod is 16.5 feet, or the length of a standard canoe. Calculating our trek in miles would give most folks a headache, but our crew is fluent in this language. Kjos’ old man and Shaver both guided canoe trips in the BWCA, and Leaf has been fishing here since he was a kid. Now that Leaf and Shaver run Sportsmen for the Boundary Waters, they spend most of their waking hours within or working on behalf of the wilderness.

“Once we cross this lake, we have the big portage at 428 rods,” Leaf continues. “That puts us on Tuscarora. I’d like to camp here.” He points to a channel he says usually holds lake trout. We figure the portage is just over a mile long (1.3, if you do the math), or a quarter of our pack in. Leaf swaps the map for an auger, Shaver hand-drills through the ice, and Kjos dips his camp mug to replace the water I’ve slopped out of the bait bucket. Kjos slurps a mouthful of the unfiltered water, then repacks the mug.

Rocky Past, Uncertain Future

The portages we’re navigating with newfangled gear were bushwhacked on ancient bedrock. The oldest rocks in the wilderness formed 2.7 billion years ago, which also makes them some of the oldest specimens in North America. The pockmarked lake system visitors see today is the result of the most recent ice age. Huge glaciers advanced on northern Minnesota, bulldozing the landscape as they froze and melted for millennia. When the last glacier retreated some 12,000 years ago, it left depressions that eventually filled with water. Paleo-Indians moved to the area, followed by the Dakota and Ojibwe tribes, cementing the Boundary Waters as both a natural and cultural touchstone in human history.

The epicenter of a more modern matter lies embedded in the area’s younger rocks. The Duluth Complex, a billion-year-old mass of once-molten rock, now covers the eastern half of the BWCA, stretching north from Duluth to Canada, west to the town of Ely, and east along Lake Superior. It contains our destination, Tuscarora Lake, at its northern edge and, below its surface, some 4 billion tons of copper, nickel, and precious metals.

This mother lode is the second-largest known copper deposit and the third-largest known nickel deposit in the world, according to MiningMinnesota.com. Trouble is, all that buried treasure is contained in rock that also contains sulfides. And while Minnesota is acclaimed for its taconite and iron-ore mines, copper-nickel sulfide mining has never been tried in the state. And it’s not without risks.

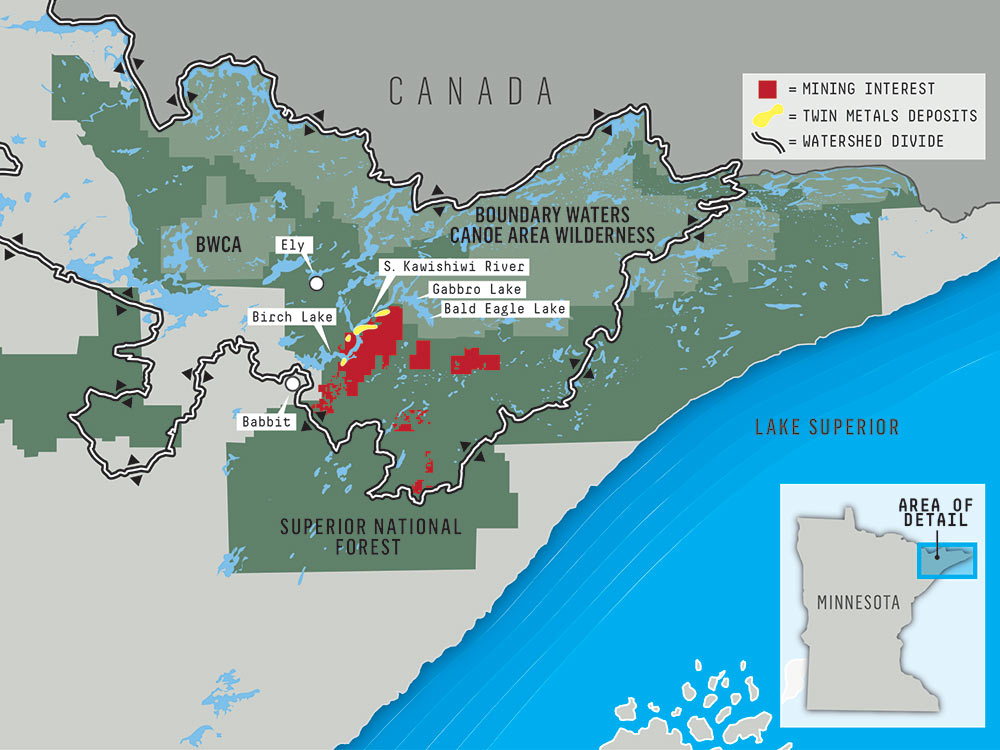

To be clear, mining isn’t allowed in the BWCA. Neither are activities like logging or motor vehicle use, all of which are commonly restricted in wildernesses. There’s also a mining buffer zone adjacent to some of the wilderness. Still, many deposits lie below the Superior National Forest, which allows mineral leasing. These leases have been the subject of a mind-numbing tug of war between mining and conservation groups spanning several administrations and courtrooms. The takeaway, however, is that these remarkable deposits occur not only in the same watershed as the BWCA, Quetico Provincial Park, and Voyageurs National Park, but also upstream from some of these parks’ major waterways and the BWCA’s tourist-attracting gateway: Ely.

Twin Metals, a Minnesota-based subsidiary of the Chilean mining company Antofagasta PLC, hopes to build an underground operation to extract these minerals. The company has already invested some $350 million in the planned $2.8 billion mine and the surrounding area—a fraction of the estimated $500 billion value of the subsurface deposit. Mine supporters expect local economic benefits and note the importance of copper components in sustainable products like windmills and electric cars. But this venture is primarily a money-making enterprise, and one that Twin Metals insists won’t impact local waters and wildlife.

Critics doubt Twin Metals will be able to deliver on that promise, citing a laundry list of failed copper mines. Phil Larson, a Duluth-based consultant who has worked in mining and mineral exploration for 20 years, dismisses these examples, saying many of those sites existed before modern regulation or involved a different kind of copper deposit. But all mining operations involve the possibility of environmental consequences to local resources. So, regardless of what risks Twin Metals calculates for its mine, most Boundary Waters advocates say any risk to its unspoiled resources is unacceptable.

Lake Wobegone

We make good time, reaching Tuscarora early in the afternoon. After strapping on snowshoes to break new trail for another mile, we find our chosen site on the ice, sheltered by a pine-crowded bluff. The outcropping is troctolite, a spotted rock geologists liken to a trout’s back. But the four of us are more interested in real trout, and we hurry to set up camp.

Almost immediately we discover the tent’s canvas doesn’t quite fit its frame. Worse are the missing guy-line anchors; there are no ice screws or stakes. We’re upending the tent bags when Leaf announces he can’t find the pin to join the auger handle with the blade. The backup auger is chipped and won’t cut ice at all. The wind picks up as we search for anchors and tug at the ill-fitting tent.

Despite months of planning and our collective expertise, things are going awry. Our mistakes in such unpredictable and unforgiving country are unwise. Two years ago and 20 miles east of here, a man named Craig Walz—Minnesota governor Tim Walz’s brother—was camping when a summer storm swept through the BWCA. High winds and torrential rain tipped a pine as Walz and his party ran for cover. The tree struck Walz, killing him and injuring his son. Last summer, a father of three drowned when his canoe capsized on Parent Lake.

My hands are growing numb as the wind whips away all the body heat I generated on the trek. Eventually Shaver suggests using a deadman’s anchor, wherein we loop each line beneath a trekking pole and bury it in the snow. After some trial and error, we discover this works well and repeat it with more poles and rocks, trying not to think about excavating them in a few days. Meanwhile, Leaf sacrificed a tip-up to resurrect the auger, stealing a screw and inserting it in place of the lost pin. Once it’s wrapped in duct tape, the auger proves secure enough to drill a water hole by the tent, then several more across the channel. But nothing bites, and dark settles around us.

Civilian War

Winter in the Boundary Waters isn’t exactly peak season, but it’s still popular for skiing, snowshoeing, and ice fishing. Summer paddlers make the BWCA the nation’s most visited wilderness, with the Forest Service reporting 250,000 annual visitors to its 1.1 million acres.

Ely native and resort owner Joe Baltich disputes those figures, saying numbers of tourists to his business have declined for years. In 1939, Baltich’s grandfather built the first cabin of what’s now the Northwind Lodge, where Baltich counts on visitors to book rooms or buy tackle and pricey Kevlar canoes. His shop, referred to as a “little Cabela’s” for the 25,000 lures stocked in its heyday, has downsized due to lack of demand. In a trendy refrain, he’s blaming kids these days for its decline.

“We’re losing an entire generation of people who hunt and fish, because millennials drink craft beer and fly drones,” Baltich says. He argues that the tourism industry can’t be fixed, saying most of those jobs are seasonal and compensated at low hourly rates without benefits. To him, a mine seems like a viable solution for injecting salaried jobs into Ely. Twin Metals’ website promises 650 full-time jobs and 1,300 spinoff jobs to the area. Opponents point to other projections cited by Twin Metals that account for only 427 direct and 918 indirect jobs.

Regardless of the exact numbers, both sides agree the mine would create some new jobs. But a recent independent study from Harvard University found that protecting the BWCA would produce greater long-term economic benefit than the proposed mine. Tourism is big business around the BWCA, and copper mining in the watershed could threaten the $288 million in visitor spending each year that supports 4,490 local jobs—not to mention minimums of $402 million in lost annual income and $344 million in lost property value.

As for millennials, Ely outfitter Jason Zabokrtsky says they’re his best customers. He’s been tracking customer data for the last three years, and the average age of his clients was 33 in 2017. The traditional tourism business model is simply changing, Zabokrtsky argues, and a mine would kill its growth potential.

“We’re building an economy off something extraordinarily unique and in extraordinarily high demand, and that’s the BWCA,” he says. “It’s not just about an outfitter renting a canoe. People are willing to move to Ely and bring mobile jobs with them so they can enjoy a high quality of life.”

Two such examples are Steve and Nancy Piragis. The couple originally came to Ely in 1975 as contract biologists for the EPA but soon became residents who opened an outfitting operation.

“Our jobs are not crappy jobs,” Steve says. “We’re a tourism-related business with a national following and a retail catalog. My first employee just retired after 36 years. We have people who stay with us for years—they get paid well and they have full benefits.”

When the Piragises arrived in Ely, Steve says, they were generally welcomed. In the years since, some residents have become more protective of the town’s heritage. A few have boycotted the Piragis’ business (along with other pro-wilderness businesses in the area) after they sided with BWCA protection efforts.

“If you weren’t born here, or if your grandparents weren’t born here, then you were—as we were called—‘packsackers,’ invaders from the outside changing things about what locals had grown to love and know and believe that Ely is,” Steve says. “Every community changes, and Ely is certainly one of those places that’s changed a lot in the last 50 years. Mining in Ely went away in the ’60s. I think people still have great nostalgia for that era.”

Despite some continued local resentment about outsiders developing the tourism industry, mine supporters welcome the idea of new residents manning the proposed mine. Baltich, who founded the group Fight for Mining Minnesota, is excited about new mining families in Ely that could stanch its declining population. But Baltich says he will stop supporting the mine if the review process reveals undue risk to his backyard. Outsiders may have turned this issue into a national fight, but Baltich and his community will have to live with the outcome. And public opinion is strong: According to a conservative pollster who worked on the Trump campaign, 70 percent of Minnesotans favored protections for the BWCA over mining interests in 2018.

Land of Plenty

It only takes one laker to crack Leaf’s cool the next morning. The 18-inch trout is spotted bronze and gaping in the freezing air. Leaf is almost out of breath too, shaking as if he’d just shot a deer. The trout had inhaled the minnow, springing the tip-up and bringing Leaf sprinting. Minutes later, Shaver jigs another onto the ice with a gold spoon in its lip. By nightfall there’s a third pair of fillets, all of which Leaf fries for supper and we eat smothered in hot sauce.

The next day we keep vigil over the holes, sitting far enough from each other for solitary fishing, but close enough to compare notes while swapping lures and drilling holes. We’re approaching limits (two per person) when bait starts to vanish off the hooks. I pinch salted shiners in half, baiting mine over and over again as the chunks disappear just as fast.

When my fingers numb to the point of clumsiness, I strap on snowshoes and a pulk, and waddle to a nearby island for firewood. I’m halfway there when I hear a shout and turn to see Shaver motionless, staring down one of the holes. It turns out he had hooked a big fish and patiently reeled until, at last, the scarred snout of a big pike broke the surface. The pike was 2 feet up when the line snapped and the fish splashed back, momentarily stunned. As Shaver reached to land it, it thrashed, then vanished.

Shaver stares after it for a long minute, then seizes a chunk of snow and hurls it. This is the first time I’ve seen him waver from his cheerful self. The second is our last night in camp as he tends the fire. Stewing on the possibility that the mine might move forward, he rests his face in his hands, then scrubs them across his windburned cheeks and through his hair in frustration. “I really hope this works,” he says softly, more to himself than me.

Shaver specializes in conservation policy, and the most recent developments in the mine’s approval process have him baffled. In October 2018, Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke withdrew some 30,000 federal acres near Yellowstone National Park (in his home state of Montana) from mining for 20 years.

“I fully support multiple use of public lands, but multiple use is about balance and knowing that not all areas are right for all uses,” Zinke said. “There are places where it is appropriate to mine and places where it is not. Paradise Valley is one of the areas it’s not.”

The Obama administration attempted to enact a similar 20-year ban on the land containing the Twin Metals leases. Not only was the ban overturned, but the Trump administration also canceled an in-progress Environmental Impact Statement in January 2018, downgrading it to a less rigorous Environmental Assessment. The administration then canceled that study in September 2018—despite a guarantee from Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue that his agency would complete it—saying no new information had been found. Sportsmen for the Boundary Waters and representatives on the House Committee for Natural Resources asked to see reports from these partially completed, taxpayer-funded studies, but the Forest Service hasn’t produced them.

“I saw this place change people’s lives for the better,” Shaver says of his time guiding in the BWCA. “It had a really personal impact on me. And after my brother’s first Boundary Waters trip, he decided to join the military because of what he experienced there. The BWCA is so deeply ingrained in what it means to be a Minnesotan. I really can’t envision a future for myself or future generations of Minnesotans without it. Anything but a perfectly protected wilderness is unacceptable. It’s some of the best backcountry hunting and fishing here in the Midwest. And we don’t have wilderness like the West has wilderness—we just have the Boundary Waters.”

The Long Haul

I’m collecting more firewood on the last afternoon when I spot a bundled figure sprinting toward Kjos, and another right behind. It’s too far to hear what they’re shouting, but there’s only one reason everyone would be running like that: Kjos just caught the pike. Sticks fall from my arms as I start to run too.

We don’t talk much on the hike out. The gap between each pulk begins to grow: Leaf’s knee is bothering him, and Kjos’ back aches. It’s all I can do to climb the trail in front of me, digging my snowshoes into the slope and clawing with a trekking pole to keep from backsliding. I push sweaty hair out of my eyes, gasping audibly and cursing inwardly. Shaver plows through the trees ahead, unfazed.

The trip ends as we cross the invisible border between wilderness and national forest. The landscape looks unchanged, and there’s half a portage and a lake to go, but the spell is broken just the same. If visiting wilderness grants “freedom from the tyranny of wires, bells, schedules, and pressing responsibility,” as Sigurd F. Olson—Minnesota’s Aldo Leopold—put it, then returning surely promises renewed servitude. True wilderness is a sanctuary from the side effects of civilization, and it’s our first responsibility to keep it that way.

The final outcome of the Twin Metals deposits and the fate of the Boundary Waters will remain uncertain for years. Currently, Twin Metals is free to resume drilling and sampling existing leases, and to apply for more. In December, the BLM renewed two leases, and launched a short 30-day public comment period that coincided with the holidays and the on-going federal government shutdown. Next, the company will try to secure control over the minerals and public land it’s already exploring. Finally, Twin Metals will write a mine plan and submit it for federal review. Sportsmen for the Boundary Waters and other conservation groups will continue to challenge every lease, of which there are dozens, in court.

On the last lake, ski tracks give way to snowmobile treads. Eventually, the parking lot materializes, and I’m relieved to see it, but resent it a little too. Ahead of me are a hamburger, a hot shower, and an inbox choked with emails. Behind me lies an unrivaled expanse of north country, free of human interference except for a few primitive campsites and the tracks we left behind. Our camp on Tuscarora looked well used when we departed: trampled snow, holes in the ice, firewood bark, yellow-edged sinkholes in the drifts. But when the next blizzard blows through this ancient landscape, all that will disappear under a blanket of fresh snow as if it had never been.