When cold and flu season arrives, it’s usually not a question of if you’re going to get sick, but when. The same holds true for deer. Even the healthiest deer live hard lives, and certain conditions — like food scarcity, brutal winter weather, drought, overpopulation, etc. — can make deer vulnerable to illness, parasites, and injury. That’s why deer disease is a major topic of discussion and study for wildlife experts, and the list of conditions, symptoms, and their consequences is extensive. So we caught up with a wildlife biologist and a wildlife disease ecologist to get the low-down on some of the most common deer diseases you might encounter, and what you need to know about htem.

The Most Common Deer Diseases

These nine deer diseases and conditions are some of the biggest causes for concern among wildlife disease experts today. They fall into four broad categories based on what causes them: bacteria, viruses, parasites, or prions. We did not include any genetic disorders that cause health complications like piebaldism, nor do we mention minor parasites that aren’t a real risk to deer, like nasal botfly larvae. With those rules in mind, we will cover:

- Arterial worm

- Brain abscess

- Brainworm

- Bovine tuberculosis

- Chronic wasting disease

- Dermatophilosis

- Giant liver flukes

- Hemorrhagic disease (EHD and blue tongue)

- Papillomas

Are Deer Diseases Treatable?

Treatments don’t exist for most of these deer diseases, and the medications that do improve symptoms are largely intended for livestock or pets. And by the time most sick deer reach the Cornell Wildlife Health Lab, says wildlife disease ecologist and director of the lab Dr. Krysten Schuler, they’re already dead.

“We do want to look at these [conditions], but it has to be within reason,” says Schuler, whose job is to diagnose deer disease and support the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation in their wildlife management efforts. “And there’s not always a good outcome for the animal. There are good wildlife hospitals and rehabilitators, but by the time the animals get to us, that’s really the end stage.”

Read Next: The Best Skinning Knives

Agencies manage whole herds and populations for disease resilience and overall health and well-being, Schuler says, which improves each individual deer’s chances of avoiding and surviving disease outbreaks. Hunters also play a crucial role by observing and reporting sick deer to their state agencies.

“It’s incredibly important for the public to report sick and dying animals,” says Matt Ross, wildlife biologist and director of conservation for the National Deer Association. “A lot of people may not do that, but we need you to report that stuff because that’s how we get a better sense of what’s going on.”

By that, Ross means that while it might be too late to save that individual deer, knowing what sickened or killed it can help officials monitor and manage outbreaks and learn more about rarer deer diseases. This intel can help inform the public about what’s happening with their deer herds.

Bacterial Infections in Deer

A deer’s hide is covered in naturally-occurring, living bacteria. That bacterial presence is normal and healthy. Trouble arises when that bacteria enters a wound, when bad bacteria is introduced to a deer’s system, or when the good bacteria gets out of balance (which often causes skin problems). Bacterial infections in humans, pets, and livestock are often treated with antibiotics, but that’s an option for wild deer for obvious reasons.

Bovine Tuberculosis

Photograph by the Michigan Department of Natural Resoures

Currently, bovine tuberculosis only exists in wild deer herds in the Upper Midwest. But because it can pass to humans, it’s worth mentioning here. Most cases of bovine tuberculosis in humans come from consumption of unpasteurized dairy products, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

What is bovine tuberculosis?

The same bacteria that causes tuberculosis in cattle and captive cervids, Mycobacterium bovis, can infect free-roaming whitetail deer through respiratory transmission, the same way you catch a cold when a buddy coughs on you. An early-stage tuberculosis-infected deer might have pus-filled abscesses and lesions on the walls of its chest cavity and lungs, which are only visible once you’ve field dressed the deer. Lesions might also appear on the deer’s lymph nodes.

Symptoms of bovine tuberculosis in deer

Respiratory illness, coughing, nasal discharge, wheezing, fatigue, trouble breathing, emaciation, lethargy, and lesions in chest cavity and/or on lymph nodes. Bovine tuberculosis is sometimes fatal for deer.

Can I eat meat from a deer with bovine tuberculosis?

While the disease passes through respiratory transmission, it can also pass through contact with an open wound. That’s why hunters are more likely to contract bovine tuberculosis from wild deer than nonhunters. Wearing gloves while field dressing deer is a good way to prevent catching bovine tuberculosis.

Brain Abscess

Photograph by Natalie Krebs

A brain abscess occurs when a head wound becomes seriously infected and puts pressure on the brain. Bucks often sustain head injuries while fighting during the rut, and are therefore more likely to contract this deer disease.

What is brain abscess?

A strain of naturally-occurring skin bacteria called Trueperella pyogenes enters a flesh wound on a buck’s head. It eats through the skull into the brain case, where it grows. Pretty soon, a large, pus-filled abscess takes up some portion of the buck’s skull.

Symptoms of brain abscess in deer

A deer with a brain abscess may have a visible wound on its head, swollen eyes, swollen joints, or foot sores. A deer with a broken pedicle or hole in the head may be at risk for a brain abscess. Usually head trauma is followed by fever, lethargy, and poor coordination. A brain abscess is always fatal.

Can I still eat the meat from a deer with brain abscess?

No. This type of bacterial infection can spread in the deer’s bloodstream and therefore hunters should not knowingly eat meat from a buck with brain abscess.

Dermatophilosis

Photograph courtesy of the NYS Wildlife Health Program

Also known as “rain rot,” this crusty skin condition can also affect other cervids like elk and moose, as well as livestock.

What is dermatophilosis?

A unique bacterium called Dermatophilus congolensis, which behaves more like a fungus than bacteria, proliferates on the skin in wet, warm, and dirty conditions. That overabundance of bacteria wreaks havoc on the host deer’s hide.

Symptoms of dermatophilosis in deer

Lesions, hair loss, pustules, and sores. Dermatophilosis in deer is often mistaken for mange. Dermatophilosis looks gross, but it’s rarely fatal for deer.

Can I still eat the meat from a deer with dermatophilosis?

While this infection doesn’t affect a deer’s muscles, it can pass to humans easily and cause lesions and sores on any skin that touches the deer. Consider avoiding a deer with dermatophilosis altogether, or wearing gloves if you have no choice but to touch one.

Viruses in Deer

Viruses are nonliving microbes that can cause everything from giant skin warts to death in deer. Unlike living bacteria, which can be killed with antibiotics, viruses don’t have cures and infected deer often die from them.

Hemorrhagic Diseases

Photograph by New York State Department of Environmental Conservation

The two primary hemorrhagic diseases that deer can contract, epizootic hemorrhagic disease and blue tongue, are very closely related and cause similar symptoms. The only difference between the two is the specific virus that causes them. In general, deer catch EHD while livestock catch blue tongue, but deer can also contract blue tongue in rare instances. Be on the lookout for these viruses during the warm summer months when biting bugs are especially prevalent. If you find a dead deer near water, there’s a good chance it died from EHD; the fever associated with the disease pushes the deer toward water sources, Schuler says.

What is EHD?

Small, biting midges pass this viral disease to deer. Deer can’t transmit it to each other, but that doesn’t stop it from being arguably the deadliest deer disease in North America. EHD is especially problematic in the Southeast, Midwest, and the Great Plains. Deer with EHD usually die within two weeks of infection.

Symptoms of EHD in deer

Fatigue, poor coordination, and bruising and severe swelling in the mouth, head, neck, and tongue. Symptoms appear within 2 to 10 days of infection, and deer usually die within two days of experiencing symptoms. On rare occasions, deer will survive EHD. Look for cracked hooves as a sign that they lived through this deer disease.

Can I still eat the meat from a deer with EHD?

Eating the meat from a deer that is visibly ill with EHD is not recommended. Testing for the disease after harvesting the deer isn’t necessary, since symptoms are almost always immediately visible in an infected deer.

Papillomas

Photograph by Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources

Otherwise known as “cutaneous fibromas,” these large, unsightly deer warts might gross you out. While they might look like a sign of some gruesome internal disease, they are actually pretty harmless.

What are papillomas?

Papillomas are caused by a virus and can be spread around a deer’s body if they lick one affected area and then lick an unaffected area. They can grow to the size of large grapefruits and will even sometimes fall off, but they don’t usually impact the deer’s overall health. In rare cases the warts can grow so large that they obstruct the deer’s airways or impede its movement.

Symptoms of papillomas in deer

Warts ranging in size from an engorged tick to a large grapefruit anywhere on the body. Unless they cause breathing or movement problems, papillomas are rarely fatal for deer.

Can I still eat the meat from a deer with papillomas?

Yes, meat from a deer with papillomas is definitely still safe to eat. Consider wearing gloves and taking extra precautions when field dressing and skinning the deer.

Parasites in Deer

Parasites are living, multi-celled organisms that survive by feeding on (and often living inside) a host animal. From hair-thin worms to giant grubs, deer live with a variety of parasites that might make your skin crawl. Luckily, most of them are pretty harmless.

Arterial Worm

Photograph by Montana Fish Wildlife and Parks

If you’ve ever seen a deer with a large lump of unswallowed food stuck in its cheek, it probably had arterial worm.

What is arterial worm?

When a host fly bites a deer, roundworm larvae travel from the mouthparts of the fly into a deer’s bloodstream. Those larvae eventually end up in the deer’s carotid artery, which runs along its neck. If the worms grow big enough, they can obstruct blood flow to the deer’s jaw, impeding the deer’s ability to chew and swallow properly. This can result in a ball of impacted food, almost like a lip full of chewing tobacco, stuck in the deer’s mouth and causing complications.

Symptoms of arterial worm in deer

A golfball- to grapefruit-sized lump in a deer’s mouth is a classic sign of arterial worm. If the impaction is bad enough, it could cause a secondary infection, but this is unlikely. Arterial worm is rarely fatal to deer unless it causes infection or leads to a complete inability to consume food.

Photograph by the Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study

Can I still eat the meat from a deer with arterial worm?

Yes if the food impaction is minor. But if the deer is showing signs of secondary infection from lots of impacted food, such as a bloody, pus-filled wound or ruptured skin around the mouth, avoid eating the meat, says the NDA.

Brainworm

Photograph by the Missouri Department of Conservation

While this parasite sounds like a mind-controlling death sentence, the number of deer that actually have complications due to brainworm is surprisingly low — less than 1 percent, according to Schuler.

What is brainworm?

A brainworm is a worm as thin as a human hair that swims around in the meninges, or outer brain case, of deer. It does not usually affect deer.

Symptoms of brainworm in deer

Brainworm in deer is usually undetectable, unless eggs are deposited in the choroid plexus, or a network of blood cells and cells in the fluid-filled parts of the brain, which can cause brain swelling. Brainworm is almost never fatal to deer.

Can I still eat the meat from a deer with brainworm?

Yes. Besides, it’s unlikely you would even be able to notice if your deer had brainworm.

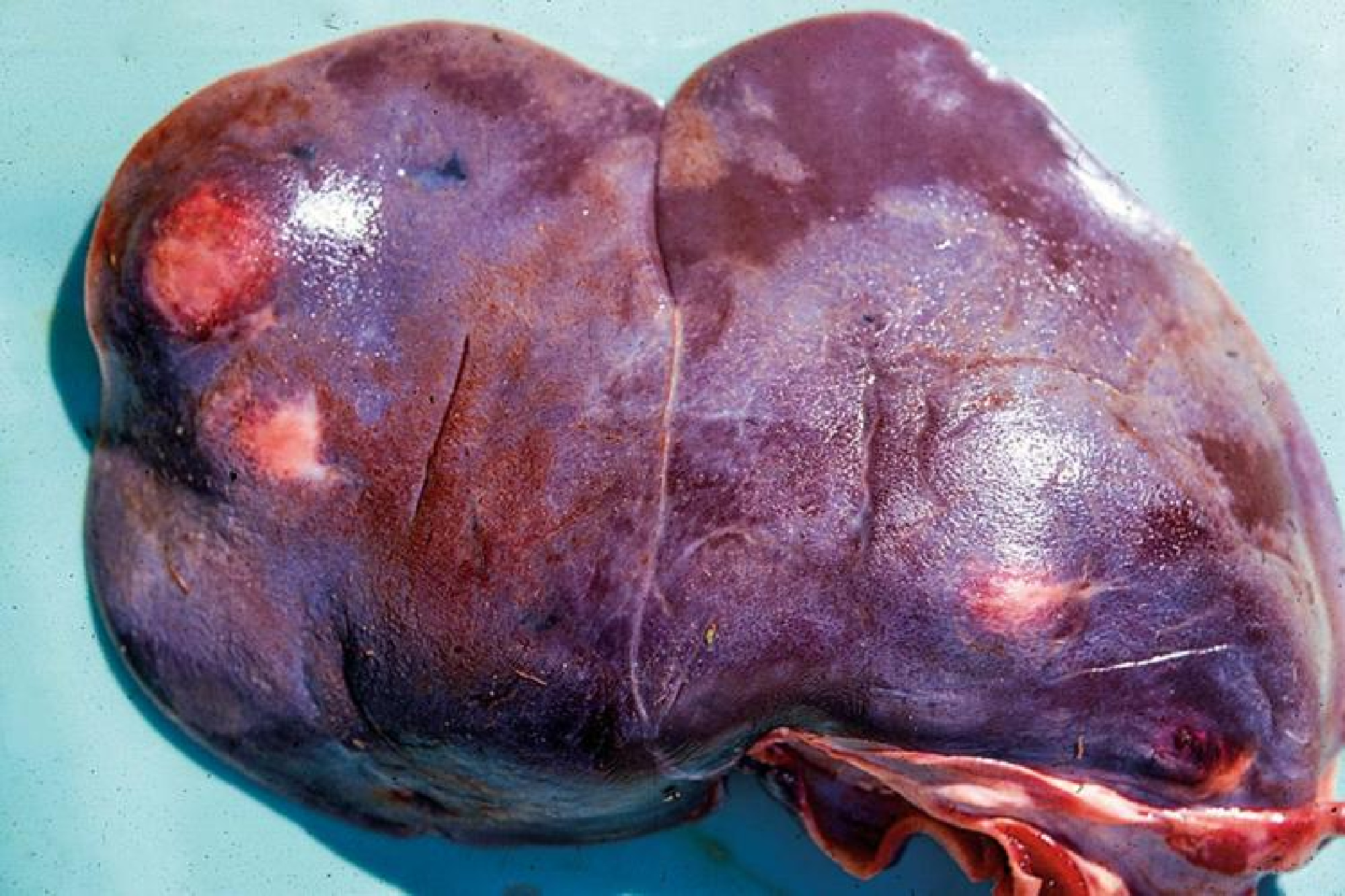

Giant Liver Flukes

Photograph by the Missouri Department of Conservation

The name sounds like a villain from a bad superhero flick, but this parasite is far more common than hunters might realize.

What are giant liver flukes?

Giant liver flukes enter a deer’s digestive system as late-stage larvae living in the deer’s food sources. The flukes travel to the deer’s liver and complete their life cycle there, laying eggs that exit back into the world through the deer’s feces. The flukes hatch on the ground and migrate to their primary host, mud snails, where they transform into the larvae, starting the cycle over again.

Symptoms of giant liver flukes in deer

No external symptoms, but a hunter might encounter large white or brown lesions or holes inside the deer’s liver reminiscent of Swiss cheese. Some of those holes will have liver flukes living inside them. The flukes are usually red or tan-brown, oval-shaped and flat, and can be up to 3 inches long. Giant liver flukes are rarely fatal to deer.

Photograph by the Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study

Can I still eat the meat from a deer with giant liver flukes?

If you can get past the ick factor, yes. Venison is unharmed by the presence of giant liver flukes as long as secondary infection in other parts of the deer’s body hasn’t occurred. Just don’t consume a fluke-infected liver.

Prion Diseases in Deer

There’s only one deer disease known to be caused by prions, but it’s iconic enough to get its own category. Mad cow disease and sheep scrapie are two other examples of prion diseases in animals that might sound familiar.

Chronic Wasting Disease

Photograph by Paul Annear

If you haven’t heard of this deer disease by now, it’s about time you did. And no, it’s not actually a zombie deer disease.

What is chronic wasting disease?

Misfolded proteins called prions essentially burn holes in the deer’s brain and cause severe physical decline before killing the deer slowly. Prions are highly contagious, especially because they can survive on licking branches and in soils for years, and it takes temperatures of over 900 degrees Fahrenheit to destroy them.

Symptoms of chronic wasting disease in deer

Deer with chronic wasting disease are symptomatic for first year or two before exhibiting lethargy, weight loss, drooling, poor coordination, and desensitization to nearby threats like people, predators, and cars. Chronic wasting disease is always fatal to deer.

Can I still eat the meat from a deer with chronic wasting disease?

You can, but you shouldn’t. There is no known case of a human contracting CWD by eating venison from an infected deer. Even so, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advise disposing of the meat from a CWD-positive deer, as do wildlife biologists, state agencies, and conservation groups.

Deer Disease FAQ

The phrase “zombie deer disease” refers to chronic wasting disease, but it’s an inaccurate nickname for CWD that does more harm than good. The name is thought to originate from how CWD-causing prions burn holes in the deer’s brain, but it also makes it sound like CWD-infected deer are stumbling around and aggressively biting other deer, which is not the case.

No, deer don’t get Lyme disease, despite how many ticks bite them every year. That’s because their blood kills Lyme-disease-causing bacteria, allowing them to coexist with ticks in relative peace.

The answer changes depending on the region. Chronic wasting disease is extremely prevalent in parts of Wyoming and Wisconsin, for example. Hemorrhagic diseases become quite widespread and prevalent in the Southeast during certain times of year.

So far, most major deer diseases don’t show any signs of jumping from deer to humans. CWD, for example, has yet to cross over to human populations. But that doesn’t mean that it couldn’t happen someday, and wildlife disease pathologists and other experts in the field are working hard to better understand those odds.

This depends on the deer’s age class and sex. The top cause of death for mature bucks is hunter harvest, whereas the top cause of death for fawns is predation.

Final Thoughts on Deer Disease

Deer, like all wildlife species, live a life that’s heavily exposed to bacteria, viruses, parasites, prions, and other naturally-occurring sources of deer disease. This shouldn’t come as a surprise — or be cause for concern.

“Deer are living laboratories,” Ross says. “They’re part of an ecosystem, just like us humans are. And the presence of these diseases shouldn’t be cause for alarm. But presence in large numbers where they’re having a negative population impact is where you should get worried. So expect these deer diseases to be out there. But it’s just a matter of understanding and identifying them, and reporting them.”