We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

I don’t know of one fishing spot in my hometown where I couldn’t find some discarded line. Look up and there’s a piece spanning the branches, a crankbait on one end hopelessly buried in the wood. Look down and you’ll find a gob of it that someone left behind after clearing and cutting out a backlash. Unless you only fish in remote wilderness, this sad scenario likely isn’t unfamiliar.

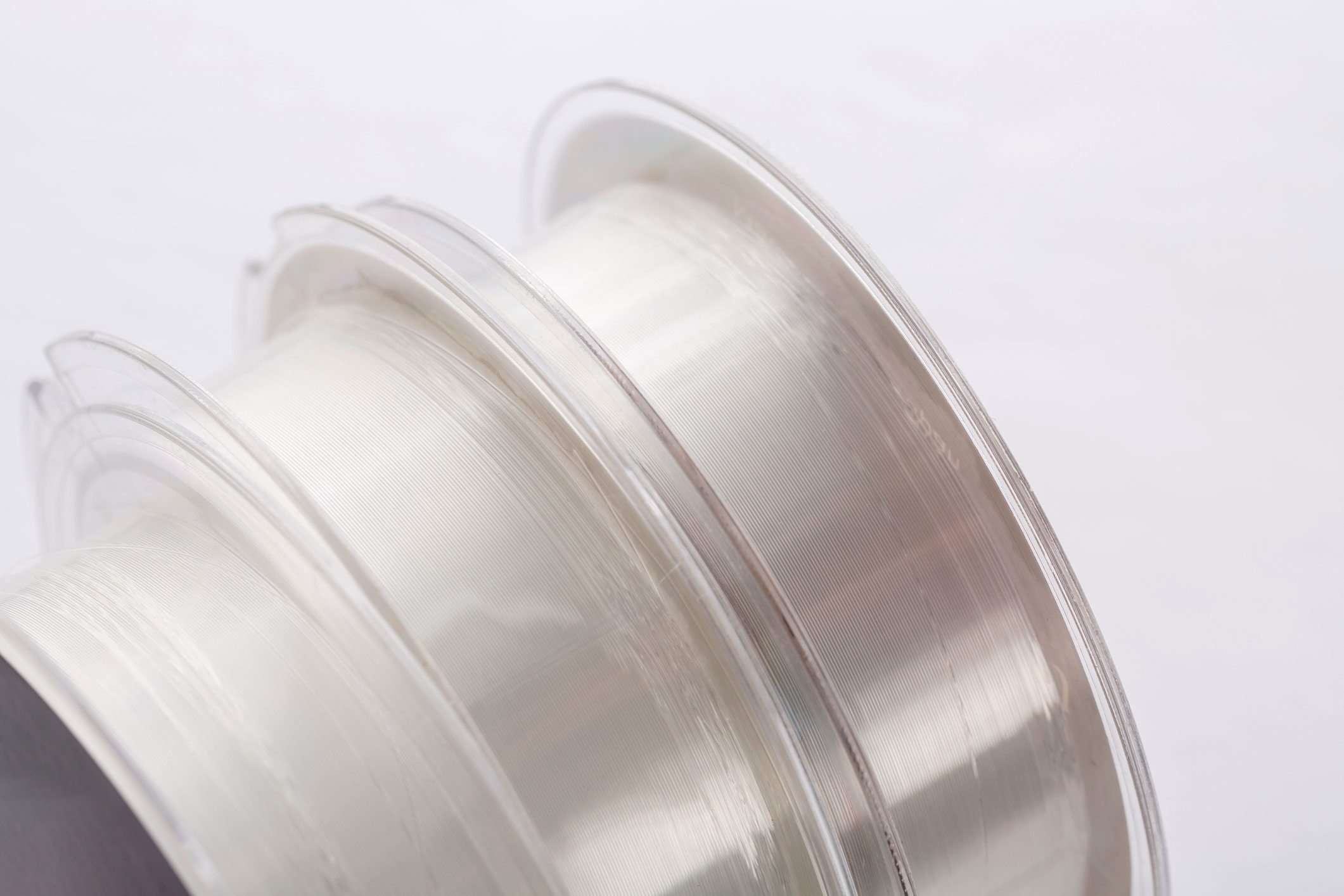

Provided I don’t have to put myself in a precarious situation to clean up someone else’s selfish mess, I try to take as much discarded line home as a I can. And while I see plenty of modern braided line in bushes and on power lines, I also find miles and miles of monofilament and fluorocarbon. From an environmental standpoint, these lines ultimately do more harm, as they’re made of composite plastics that don’t break down any faster than a Gatorade bottle or shopping bag. So, when will that fluoro leader you left by the river disappear? Inventor Nikolay Valentinovich Repnitsky is banking on never.

Permanent Record

According to this quirky story on the website Hackaday.com, Valentinovich Repnitsky created a machine that can notch fluorocarbon line as it unrolls off its spool, effectively encoding it with a language similar to Morse code. The invention can also read the encoded messages and send them to a computer. Valentinovich Repnitsky’s “Carbon Record Project” seems to be a product of home workshop tinkering, which makes it even more impressive. You can find a short video of his invention translating code here. It’s worth noting, however, that some of the reasoning behind Valentinovich Repnitsky’s work makes one question his motives. In a list of the technology’s benefits on his website he writes:

To preserve something authorities can’t kill by waiting: Fluorocarbon fishing line won’t degrade for a few thousand years. It’s cheap and easy to “write on.”

To preserve something authorities can’t kill remotely: Fluorocarbon fishing line should survive EMPs and the light of WW3 if buried, as well as solar flares.

To preserve something authorities can’t confiscate: Fluorocarbon fishing line should be a nightmare to search for if buried.

Doomsday scenarios aside, it’s hard to argue with the ingenuity of Valentinovich Repnitsky’s idea. Theoretically, a 1,200-yard spool of line—something routinely purchased by offshore captains the world over—could provide all the room you need to preserve War and Peace, the Bible, or every Nintendo cheat code ever known. Though I’d guess Valentinovich Repnitsky isn’t a hardcore angler, he inadvertently hit on a point that’s useful to fishermen. He’s correct that burying line would preserve it even longer because sunlight and heat are about the only things that will speed up the process.

Cold, Dark Truths

Water has very little effect on fluorocarbon and monofilament. They’re impervious by design. So, if you rudely tossed a wad of mono off your grandpa’s boat when you were 10, there’s a strong chance that somewhere down under the layers of lake muck, some, or all of it, still exists.

Conversely, if you’ve ever had an old fluoro or mono line snap mid cast, it’s likely because it’s been degraded by sunlight and heat. Although neither line material will disappear in a jiffy if left out in the sun, within a few years it can become brittle enough to cost you fish. This means that if Valentinovich Repnitsky was to encode a spool of fluoro and leave it on a beach in the Florida Keys, the line would still be there decades from now, but you might not be able to read its message anymore.

I can’t tell you how many spools of fluorocarbon I’ve cut leaders from that are close to a decade old. It’s blasphemy to many anglers, but the truth is that if you store your spools in a cool, dark place when you’re not on the water, 10-year-old fluorocarbon is as good as the spool you grabbed at Wal-Mart yesterday. I keep a line in a bin with a lid in the laundry room in my basement. It’s pitch-dark most of the time and cool year-round. I’ve even known a few charter captains who, after spending upwards of a hundred dollars on bulk spools of line, would stash them in their chest freezers.

Now, while I don’t think Valentinovich Repnitsky’s invention is going to inspire any of you to start encoding spools of line with your secrets to fishing success to help a post-apocalyptic society feed themselves, his choice of medium should be sobering. Pick up your line and any other line you see so that it’s not tangled up in the environment for eternity. It’s as simple as that. Opting not to do so says more about you than any fluorocarbon record book likely ever will.