Editor’s Note: This has been a tough year for everyone. And while we’ve collectively experienced many of the same events, the changes, challenges, and often outright hardships everyone has endured remain deeply personal. We asked six contributors to look back on 2020 and reflect on how the events of this year shaped their lives, in ways both big and small. We will be publishing one essay each day through the end of the year, on topics ranging from subtle differences at deer camp to the enormous task of parenting during a pandemic. You can find all the stories, as they’re published, right here.

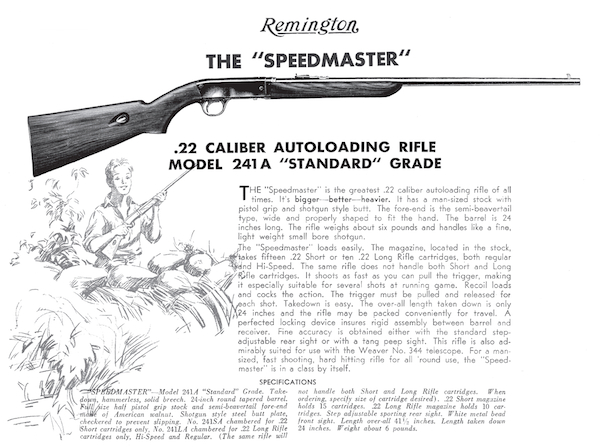

A sooty grouse, colloquially called a “hooter” in Southeast Alaska, hooted from a stand of spruce trees on a steep mountainside. I snowshoed toward it, carrying my 15-month-old son on my back, until I was just above the grouse. The bird, puffed up and bobbing as it called, materialized through a maze of branches. I aimed my .22 and, at the crack of my shot, the bird plummeted from its perch. A few minutes later, my boy clutched the grouse to his chest and began chewing on it. He looked up with a mouthful of feathers and said, “Bye-bye, bird.” At the end of the day, with a sleeping boy and a few birds in my backpack, I stared out at snowy mountains stretching in all directions and thought about how this is as good as it gets.

Like a lot of people, 2020 was kicking my family’s ass. Southeast Alaska’s economy is heavily dependent on tourism—around a million visitors come each year, mostly on cruise ships. This sort of tourism can be overwhelming with the added boat and air traffic. So, when it became clear that there wasn’t going to be a cruise season due to COVID-19, many locals looked forward to having our home to ourselves. My main employment consists of guiding wildlife film crews, but nearly every production I’d been scheduled to work on had been canceled due to the pandemic. I hiked down through the shadowy rainforest with my sleeping boy, wondering how I was going to make ends meet.

RELATED:

Since I was unemployed, I decided to make the most of it. I spent a lot of May and June in the field, hunting grouse with my son and watching brown bears. I know that other folks spent more time hunting, fishing, and hiking, too. The mountains saw an unprecedented number of people seeking solace in the adventure and peace they offered. I might have been solitary in the wild places I was going, but I wasn’t alone in my reasons for going there.

My most notable trip was to Kadashan Bay on Chichagof Island. One evening, I counted 35 different brown bears eating sedge grass and courting. Biologists recognize Kadashan for its exceptional brown bear habitat and for being one of the highest producers of salmon in northern Southeast Alaska. Decades ago the Forest Service had facilitated the clearcut logging of much of the surrounding watersheds and mountains—destroying public land and habitat needed by Sitka blacktail deer, brown bears, and other wildlife. In 1984, Kadashan was slated to be cut. The Forest Service began blazing a road up the drainage but, but thanks to the work of biologists and conservation groups, a judge granted the watershed permanent protection before logging could begin.

On the mainland north of Chichagof Island, I looked for wolf dens with a friend. When we found an old and seemingly abandoned one, a pack began howling from a ridge a half mile away. Twice, while we drank coffee next to a campfire in the early morning, wolves visited and studied us. When I returned home, my lady, MC, told me she was pregnant. I was surprised, and we were both nervous about having a kid during a such a chaotic time.

Instead of panicking, I took my son to Admiralty Island. We traveled bear trails through towering old-growth forest and watched bears peacefully going about their lives. At night, I studied my boy sleeping and thought of my dad and his core “sisu” philosophy. In Finnish, “sisu” means strength and perseverance, even when things seem entirely hopeless, even to the point of insanity. This philosophy has benefited me during times in wilderness when things went wrong, but it was another thing to apply sisu to the more obscure challenges faced in regular life. My dad again showed me the way, by taking care of a loved one whose health issues seemed impossible to beat. Through it all, he never relented. Plain and simple, you just don’t give up—no matter what you’re faced with. You keep going until your heart gives out.

In July, with salmon returning to spawn, I lucked out and was able to guide a brown bear shoot. Because of the pandemic, the team was small. Two guys showed up: the renowned wildlife camera operator Shane Moore and Lucas Mullen, a hunting guide and commercial fisherman who acted as boat support. During the two months Shane and I worked together, we talked a lot about our shared love for wild places and public lands. The pandemic had only made clearer how invaluable these wild places are. In early October, I returned home and was caught off guard by how big my boy, and MC’s belly, had gotten in my absence.

I made one last trip to Admiralty Island in mid-November to thank the bears for another year and to fill my freezer with Sitka blacktail meat. One afternoon, I came across fresh bear tracks wending through the snow-covered boulders of an old landslide. Perhaps he was going into his winter den. An hour later, I shot a young buck in the forest fringe, then dragged him onto the beach to butcher. I sharpened my knife and looked at the mountains, rainforest, and ocean. Before I cut into him, I whispered a quiet thanks.

Bjorn Dihle is a lifelong Southeast Alaskan. His next book, A Shape in the Dark: Living and Dying with Brown Bears, is scheduled to be released mid-February.