During the first decades of the 20th century, a murderous trapper haunted the upper watersheds draining into Bristol Bay and the Kuskokwim River. His life, identity, and even death are shrouded in mystery. Newspapers claimed he was Yup’ik, and that he murdered an unknown number of people—mostly trappers and prospectors that crowded his vast territory. He was called Klutuk, named after a small tributary of the Nushagak River where one of his camps was located. The Kusko Times reported in 1931 that Klutuk “was born in the Nushagak River district about 38 years ago. He first became notorious in 1919, when it is said his career of crime started by killing two natives and announcing he would kill two more. Subsequent events indicated that he did not stop at that. From that time until his death he had the entire upper Nushagak district under his control.”

Some accounts claimed Klutuk was a giant. Others that he was small man. Some said he was more than a man. He was allegedly heard saying he viewed killing a person as no different than shooting a moose. His only companion was a small black dog. The Kusko Times wrote that it was believed he’d murdered 20 or more people and that, “Through some system unknown to the whites, he kept himself constantly in touch with what was going on throughout the district. He seemed to know when any man entered his territory and he resented all such intrusions. Disdaining to use the weapons known to civilization for his own needs, he shot his game with bow and arrow; but he packed a 30/30 rifle for his human prey.”

A Manhunt Begins

Klutuk lived during the end of the frontier mentality in western Alaska. The commercial fishery in Bristol Bay was attracting a wave of foreign fishermen and cannery workers to the coast. Further inland, investors were eying large mining developments. But besides the wild country providing its own inherent difficulties, the legend of Klutuk was stalling mining development. Sightings of Klutuk showed up from Cook Inlet to the upper Kuskokwim River. If a prospector or trapper disappeared or was murdered, it was blamed on Klutuk. He was costing both the territory of Alaska and corporations lots of money.

Territorial marshals, deputies, and friends of the murdered and disappeared began a manhunt. The search spanned thousands of square miles and lasted for years. In 1929 the Wrangell Sentinel and Kusko Times reported that Klutuk had been killed, but they didn’t give much evidence. Locals from Dillingham hinted that justice had been served but didn’t offer any details other than that no one had been murdered in the Nushagak district that winter. Sightings of Klutuk soon began being reported again. In the summer of 1931, a deputy United States marshal named Stanley Nichols reported finding a corpse in a cabin near the headwaters of the Mulchatna River that he thought was Klutuk. Nichols, no doubt under significant pressure to close the case on the mad trapper and help open the region to development, said “Klutuk” appeared to have died from natural causes. Many believed Nichol’s report was purposely falsified. But according to the authorities, Klutuk was officially dead. Newspapers across Alaska celebrated.

Another Mad Trapper Surfaces

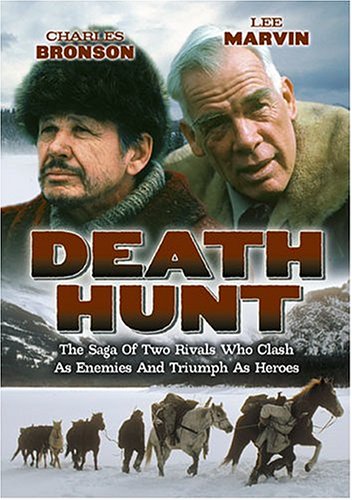

A year after Klutuk was declared deceased, another mad trapper would create a media frenzy and capture the public’s fascination for decades to come. Called the Mad Trapper of Rat River, Albert Johnson (a pseudonym) was pursued by Mounties from January 16 to February 17,, 1932 through some of the most rugged country and harshest weather conditions imaginable. Initially, he was accused of tampering with other trappers’ traplines. When Mounties approached him in his remote cabin, he wouldn’t comply with their commands, speak, or even acknowledge their presence. The Mounties returned with more men and when they tried to open Johnson’s door, the trapper fired on them. After numerous gun fights and a month-long chase, Johnson was shot dead. He was emaciated, weighing just one hundred pounds. His true identity is still unknown but, unlike Klutuk, he would be the subject of a number of articles, at least 10 books and even movies—one starring Charles Bronson as Johnson.

Read Next: 30 of the Most Legendary Hunters of All Time

Klutuk Mysteries Remain

One can only guess why the media hasn’t mined the legend of Klutuk for all it is worth. Next to nothing has been published about him. One book, published in 1990, included a chapter about him: North of Sun: A Memoir of the Alaskan Wilderness, a memoir by Fred Hatfield. The book is an Alaskan classic, even if Hatfield may not have let the truth get in the way of telling a good story throughout certain parts of his narrative.

Hatfield arrived in Alaska in 1933, two years after Klutuk officially died. He trapped out of Togiak Lake, working at the liquor store and as a fur trader in Dillingham. Later, he commercial fished from a sailboat in the Nushagak district. In 1936, an old timer named Butch Smith approached Hatfield to tell him that the Wood Tikchik Lake region could be a good place for him to trap. He warned him that it might be dangerous, though.

“Fred, there’s something I’ve got to tell you and then you can make up your mind about that country. Last year the bodies of three government surveyors were taken from the Nushagak river, at Ekwok. All three of them had been shot. Opinion seemed to be that the job had been done by an Eskimo who lived a long way up the Nushagak, name of Klutuk,” Smith said.

Smith went on to state he believed Klutuk had his winter camp about 40 miles from where Hatfield planned to trap. Smith, and two trapping partners, had run into Klutuk deep in the wilds years before. One of his companions was murdered by Klutuk—a fate that a few other friends of Smith’s shared.

Hatfield was young and cocky and brushed off the warning. He gathered his kit and hired a bush pilot to fly him in. Before leaving, Smith asked him to look for Jake Savolly, a trapper friend who’d gone missing during the past year. Not long after Hatfield got dropped off, he hiked overland to Savolly’s cabin. He found the man’s remains in the nearby woods, covered in a swarm of shrews. It was apparent he’d been shot in the back and then drug off. Savolly’s cabin had been ransacked. According to Hatfield, the discovery set off a two-year game of cat and mouse between him and Klutuk. The first winter he didn’t even set a trap he was so amped up and on guard. Two springs later, in 1938, Hatfield made his move. He left his tea can of sugar laced with strychnine in his cabin when he left to fish the summer in Bristol Bay. When Hatfield returned that fall, he found the can empty and Klutuk’s corpse outside the cabin, according to his memoir.

“Two years of being hunted were over. I had no remorse and yet I wasn’t easy in my mind. It was strange to have killed a man and look at him for the first time. Somewhere I had read that man-hunting was the king of sports. I hadn’t found it that way,” Hatfield wrote.

Hatfield was in his early 80s when he published his memoir in 1990. It was met with a firestorm of controversy by people who believed he’d either fabricated the story or, much worse, murdered an innocent traveler using his cabin for shelter. In Alaska at that time, no cabins were locked and a pile of firewood, complete with kindling and matches, always lay ready next to the stove. A state prosecutor went as far as to ask the police to open a homicide investigation. Hatfield didn’t waver in saying that he had killed Klutuk, or someone else who was trying to murder him. The man he killed, he said, was wearing mukluks with claws made from the hindfeet of a brown bear, the sort of footwear Klutuk was said to have worn. Hatfield died not long after telling his story. In an interview before his passing, he said there was nothing he would love more than to return to the wild Bristol Bay watersheds.

There weren’t many more published stories of Klutuk after that. These days, the Nushagak River is renowned as one of biggest salmon-producing watersheds in the world. The Wood Tikchik Lakes are now a state park and draw visitors to experience the regions abundance of salmon, brown bears, and beautiful scenery. The legend of Klutuk is mostly forgotten, but it stands as a stark testament to the last days of the frontier.