We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

Behold the BB. It is a simple bit of metal, formed into one of nature’s most basic shapes. There isn’t much to one. BBs measure .17 inch from side to side, weigh 5.1 grains, and can be purchased by the thousands for a few bucks.

Steel BBs start as a piece of wire that is cut into small pellets that are then squeezed into a rough sphere by a press. At this point, each BB has a ring of raised metal around its circumference where the two halves of the press meet. These imperfect globes are dumped into a tub with a scouring media, where they are churned and tumbled until they are uniformly round and smooth. As a final step, to protect against corrosion, they are coated in zinc.

You can be forgiven if you’ve never devoted much thought to BBs and how they are made. Not many people have. But that doesn’t diminish the importance of these little balls.

With few exceptions, the first time any person hoists a gun, it’s a BB gun. Whether he or she continues as a casual plinker, goes on to compete as a shooter in the Olympics, joins the military, makes hunting their life’s focus, or never picks up a firearm again, that person’s first—and perhaps only—exposure to guns started with BBs. They are the seeds from which the next generation of hunters and shooters is grown.

FAMILY AFFAIR

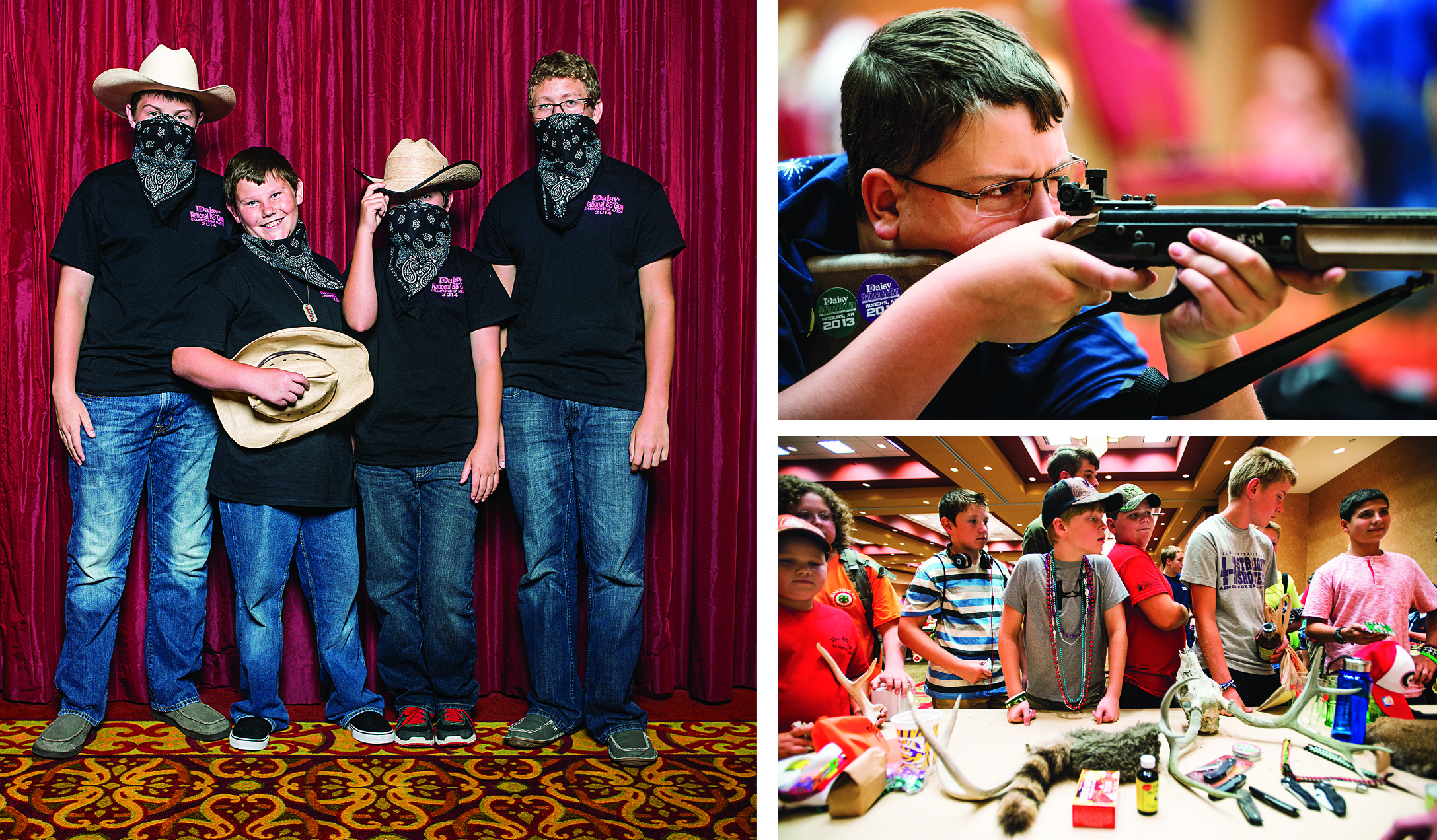

Put an aluminum can on a fence post or tape a balloon to a cardboard box, and you have the makings of a BB gun range. But there is another, more serious side to BBs. Each year in Rogers, Arkansas, the home of Daisy Outdoor Products, hundreds of children from around the country gather to put their rifle marksmanship skills to the test.

For the last 50 years, Daisy has hosted the National BB Gun Championship Match. The shooters who come to the tournament have already proven their mettle. In order to qualify, teams must have placed in the top three in a sanctioned match in their home state.

“BBs ARE THE SEEDS FROM WHICH THE NEXT GENERATION OF HUNTERS AND SHOOTERS IS GROWN.”

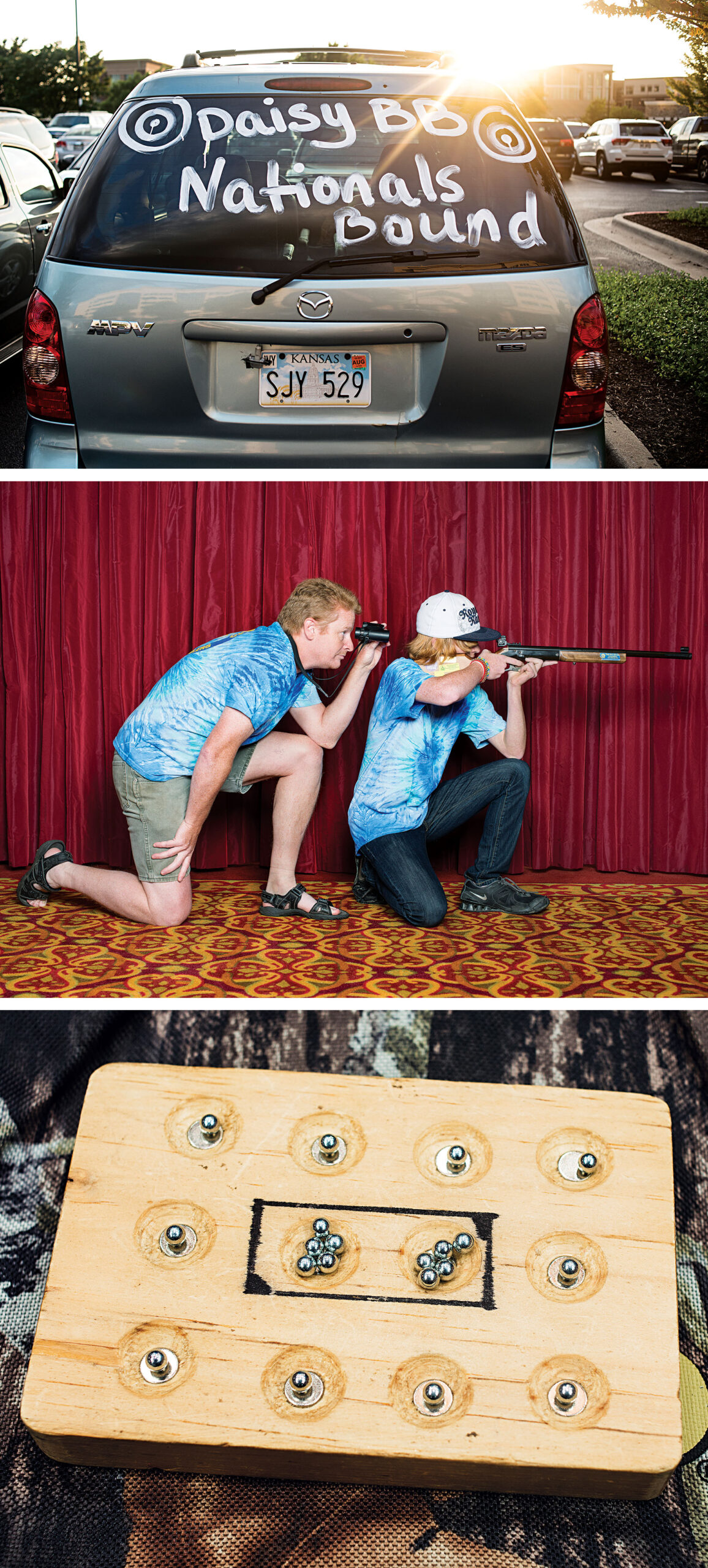

The children attending last year’s match arrived by bus, plane, and minivan, converging on Rogers just ahead of the Fourth of July weekend. The shooters were as varied as the states from which they hailed. There were young guys with hats canted to the side, rocking a California skater vibe. Some girls sported bright-pink spiked hair, while others looked ready for a cotillion. Vehicles in the parking lot of the hotel and convention center where the match takes place had been decorated for the occasion. Lengths of ribbon trailed off bumpers. Painted messages on car windows offered words of encouragement and good fortune to the shooters.

All told, 51 teams with seven shooters each competed in the championship. All of the teams had an entourage of parents, coaches, and siblings in tow.

The event is a family affair. Suzy Brown’s youngest daughter, Ellen, came to the championship to shoot, just as her 13 siblings have done before her. In fact, also on Ellen’s team is her niece, Marianna Munoz, the daughter of Suzy’s oldest child.

The Browns, who hail from Tennessee, have been involved in the program since the early ’80s. Like so many of the families here, once they caught the BB bug, they couldn’t shake it.

“My husband, Ricky, was a police officer, and we’ve always enjoyed the shooting sports,” Brown said. “This program means a lot to him. He loves to shoot and is a good coach. He has kept the team going. Other than church, this about the only thing we do together.”

Ellen Randall practices off-hand; Cassandra Ryckman shows off the medal she won as the first-place finisher out of a field of 338 shooters during the championship; changing targets during practice.

THE SHOOTING

The hotel ballroom, with its bright red-and-gold carpet, was an unusual setting for a shooting match. Most BB gun programs take place in the basements of local businesses, in warehouse facilities, and at covered show rings at county fairgrounds, not in the luxurious confines of a location with catering services.

Dozens of target stands were set up along the opposing walls of the ballroom, each illuminated by a halogen floor lamp. The stands were made of tall, sturdy cardboard boxes braced on either side with two-by-fours to keep them upright. The BBs have enough punch to penetrate the first layer of cardboard but bounce off the interior of the box, becoming trapped inside. At the end of the day, the stands rattled like maracas when moved.

The firing line was marked with a strip of lime-green tape positioned 5 meters from the boxes. The official scoring sheets have 12 circular targets on them—two are for practice sighters, the other 10 are for the record. The competitors take turns shooting strings from prone, kneeling, sitting, and standing positions. During a string, the shooters place one shot on each of the 10 targets. A shot in the tiny bull is worth 10 points. A perfect round would score 100-10 points, the extra “10” indicating the number of shots that hit the center of the 10-ring.

BEYOND MARKSMANSHIP

While shooting well is the goal of every athlete at the event, the match is the culmination of a program that had started months before, one in which the emphasis is on learning firearms safety and ethics much more than just shooting perfect scores. Part of every official BB gun program across the country is a written test that the students take to make sure they have a solid grasp of these fundamentals.

The championship is no different in this respect. A test worth 100 points toward the shooter’s final score was part of the match. A competitor who scores a perfect 400 shooting can blow it if he or she doesn’t ace the exam. As Cassandra Ryckman—a 14-year-old from Pierre, South Dakota, who took the overall high score at the match with 482-15 points, including a 100 on the exam—put it: “You can’t practice for nervousness, but you can practice for the test.”

Daisy goes to great lengths to celebrate the athletes. “It’s all about the kids.” You hear that from everyone who helps pull this event off, including the legion of unpaid volunteers, some of whom have come from hundreds of miles away. Showing the kids a good time is the guiding principal of the match. There’s no corporate shilling at the event, and no elected officials come to speak. (At the opening ceremonies, Daisy CEO Ray Hobbs announced that the match would be “politician-free” to thunderous applause.)

From the moment the shooting started on Friday morning, the air was filled with the snap and buzz of flying BBs. Kids ages 8 to 15 adjusted their slings, steadied their breathing, peered through the rear aperture sights on their Daisy Model 499s, and did their best to get a clean, smooth trigger break.

Parents and coaches knelt at their sides, loading the individual BBs for the shooters. Often, one coach will keep an eye on the muzzle of the rifle while another looks through a binocular at the target. If a shot goes astray, they confer to see whether the muzzle betrayed any unwanted movement due to poor form, or if the sights need adjusting.

ZEN MIND

The coaches never say much to the children while they’re shooting. For their part, the kids told me they try to focus only on making the shot. Ryckman clears her head every time she aims by singing a line from a nursery school ditty. “I’m bringing home a baby bumblebee,” she murmurs to herself as her rifle’s sights settle.

This is just how the coaches like it. The last thing they want is stray thoughts distracting their shooters. There’s enough pressure on them already. It is safe to say none of the children realize what goes on behind the scenes to put a rifle in their hands that can shoot a 10 with every pull of the trigger. If they did, they would probably freeze in panic.

THE GEAR

A stock Daisy Model 499 is a fine rifle out of the box, but there isn’t a 499 made that is ready to shoot in the championship without modification. The standard practice is to get several spare barrels, technically known as shot tubes, and through a process of trial and error see which shoot the best. The shot tubes are carefully fitted to the rifles and secured so they don’t come loose. The action on the triggers is smoothed out, and weight is added to the stocks to increase stability. The sights are checked to make sure they track correctly when adjusted and are replaced if they don’t.

The rifles are also custom-fit to each shooter, the stocks being cut down or extended to achieve a perfect length of pull. A rifle that is a real shooter can have a life that spans decades and will bear the scars of these repeated modifications as it is passed down from one athlete to the next.

Then there’s the ammo. Regulations stipulate that only Avanti BBs can be used in the competition—no custom-machined ball bearings allowed. While the Avanti BBs are a step above your standard carton of bargain-priced BBs, and are marketed as “precision ground shot,” the truth is that out of a package of 1,050 (a standard-size container), perhaps only 100 are good enough for competition.

Walter Sanders prepares to shoot; members of the Oregon Timber Beasts shooting team amuse themselves by building a house of cards (and shoes) during downtime.

Even the slightest imperfection on a BB can cause it to veer off-course and miss the .125-inch bull’s-eye. Every team has its own method to sort BBs, but in general each projectile is measured for concentricity and diameter. To test whether a BB is truly round, each is rolled across a smooth piece of glass as the roller listens for telltale “clicks,” indicating a flat spot. If it clicks, it is rejected.

The remaining BBs are then either put through caliber-specific gauges to make sure they are the correct size, or they are individually dropped down the shot tube of the rifle they are going to be used in.

As Lee Nelson, a BB gun coach with the Gallatin Valley Sharpshooters in Montana, explained, the drop technique operates on the Goldilocks principal. “I cover the lower end of the tube with my finger and drop the BB down,” he said. “The ones that fall too fast or too slow get put aside. The BBs that fall at a nice, steady rate are the keepers.”

It’s a tedious process, but it’s necessary.

“The accuracy you want and the accuracy that the kids deserve is for the rifle to put five in the same hole,” said David Haire from Tift County, Georgia, who has been coaching BB shooters for 17 years.

LIFE LESSONS

Despite the efforts of the coaches and parents to keep the stress on the children to a minimum, the shooters are not immune to pressures off the firing line. Just a week before the competition, Hailey Strenge, a 13-year-old from Buffalo, Minnesota, broke her arm while playing soccer. Strenge was the top shooter for the Buffalo Youth Shooting Sports team at the state match and was determined not to miss the nationals. She arrived in Rogers with a cast on her arm, ready to help her team. The match referee disqualified her because the cast was deemed to give her an unfair advantage, since no type of exterior support is allowed. Never mind that the cast was on her trigger hand and would be nothing other than a hindrance—the rules were clear.

At Hailey’s urging, her parents briefly considered cutting off the cast for the match but opted not to. Strenge appealed the ruling, but her protests were denied and she had to sit the match out.

“It’s a good life lesson,” said her grandfather Rod Strenge, who was attending the match.

Rod exemplifies the old guard, who keep the BB gun program alive. He helped start the Buffalo, Minnesota, team back in 1978 and has been part of it ever since. Because of his efforts, he was inducted into the BB gun Hall of Fame in 2011—only the third person at the time to have earned that honor.

He worries about the future of the BB gun program, worries that the older adults who form the backbone of the organization are “aging out” and that there’s not enough fresh blood to entice a new generation of shooters into the sport.

AND YET…

While gray-bearded coaches are prominent, they do not set the tone at the three-day match; the competitors do. Watching them, it is difficult not to feel optimistic about the future of the shooting sports. The poise and focus they display on the firing line is a strong counter to the stereotypical image of hyperactive or lazy teens. They have a quiet confidence while shooting that lends them an air of maturity beyond their years. At least until they step outside the room that hosts the match.

In the hallways of the center, they revert to their adolescent selves. Kids form circles, sitting cross-legged, making bracelets and other tchotchkes for the annual swap meet. Some play board games or build precarious structures from playing cards that incorporate shoes and whatever else they can get to stack.

During a contest to see who has the best paint job on a gun, they show off the wild designs and color schemes they’ve decorated their rifles with. At the costume contest on Saturday night, they go all out. The Oregon Timber Beasts dressed up as lumberjacks, one group from Kansas arrived as characters from The Wizard of Oz, and the Cajun Shooters were decked out in full Mardi Gras regalia.

Once the scores have been compiled and the results posted, the top shooters are honored at the awards ceremony on the last night.

Howard Baker, coach of the Oregon Timber Beasts, got involved with the BB gun program 36 years ago, when his son was eight years old. He’s taught hundreds of kids over the years and is now coaching one of his granddaughters. His team is not among the elite squads at Rogers, but that doesn’t matter to him.

“This is a life-learning trip for kids. They do fund-raisers and garage sales to make it happen,” he said. “We’re never going to finish at the top here, but that’s okay. My goal is for every kid to come off the firing line feeling good about themselves. When you watch these kids grow up and mature before your eyes, there’s nothing like it.”

By the end of the competition, thousands of BBs have been sent downrange, and hundreds of thousands more were shot before the kids ever arrived in Rogers, each a seed that helped make that growth possible.