Jim Williams is a hunter, biologist and conservationist in Montana. His lifelong passion has been wild cats – particularly the mysterious creature called mountain lion, cougar, or puma. His new book, Path of the Puma, traces the remarkable conservation success story of cougars across the western hemisphere. Mountain lions are staging a remarkable comeback in North America, in large part thanks to the secure habitat they find in the public lands of the American West. From there, they have stealthily spread to Wisconsin, Illinois, even Connecticut and Tennessee.

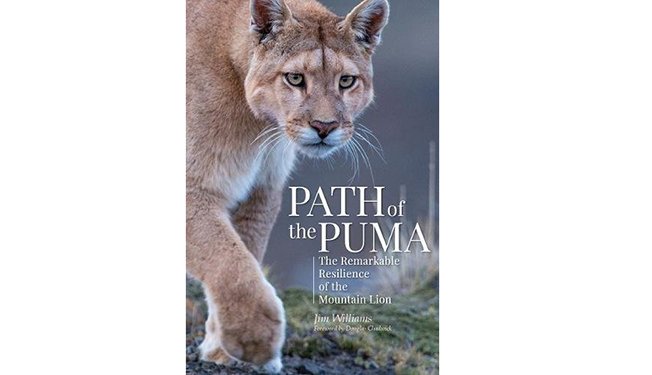

The book includes stories, mountain lion biology, and first-person experiences with the cats in the wild, spiced up with a few bar fights, harrowing hound chases, and rough-and-tumble politics. The book is richly illustrated with photographs of what few people ever see: mountain lions in the wild in the grandest corners of North and South America.

I sat down and had a conversation with Jim. The interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Ben Long: Pumas are one of the most widespread animals in the western hemisphere, yet even experienced hunters rarely see them. What makes mountain lions so mysterious?

Jim Williams: Mountain lions are a stalk-and-ambush predator that can see in low light conditions. They are walking movement-detectors. We may not see them when afield but if you are in lion country, they are always watching us.

BL: Large wild cats like tigers, jaguars and lions are in trouble all around the world. Yet the mountain lion is the exception, expanding its range. What’s the difference?

JW: We rarely see them. They are ghost cats. Their secretive nature pays off. Additionally, hunter-funded deer and elk recovery in the US has provided a ready-made grocery store for many native carnivores. Mountain lions have recovered and are moving east on the backs of whitetail deer. Will we, as a society, tolerate them in the Midwest and back East? That remains to be seen.

BL: When mountain lions become established in new areas, hunters often fear that the new predator will hammer local deer herds. You write that this is rarely a problem. Can you explain?

JW: Predator-prey relationships are often driven from the ground up. Good soils provide ample forage for deer and elk, which in turn provide food for carnivores. Mountain lions are highly territorial, so they check their own numbers. Mountain lion predation is only a negative issue for remnant, endangered caribou or isolated populations of bighorns, deer, or elk. If humans have compromised the wildlife habitat or reduced the ungulate population to a fragment of its original size, then [cougar] predation can be an issue.

BL: You write that hunters, particularly mountain lion hunters, are often the ones who speak out the loudest for conserving mountain lions. Explain your experience.

JW: Hound handlers have always been first in line to protect what they love. It was the legally licensed mountain lion hunters who worked to eliminate the bounty system, protect the cats with game animal status in the western U.S., and establish scientifically based quotas. Many hound handlers that I know photograph these cats all winter long and know where various family groups live and how many kittens they are raising.

BL: Houndsmen often see mountain lions as a great trophy animal. Anti-hunters see them as persecuted wildlife that needs protecting. Who is right?

JW: Opinions vary from person to person and are based on our own personal values, belief systems and culture. It really boils down to what local communities and or States want.

BL: Recently in the Pacific Northwest, we’ve seen one hiker and one mountain bike rider killed by mountain lions. Some argue that we need to hunt mountain lions to instill a fear of human beings. Is that a reasonable argument?

JW: No. Dead animals do not learn anything. They are dead. It’s not like they live in a group and see their buddy get shot and learn from that experience. That being said, legally licensed hunting can reduce densities but some risk of a human conflict will always be there. Human attacks rarely happen but when they do it’s tragic.

BL: You write that a 150-pound mountain lions sometimes take down adult moose that weigh nearly a half ton. How is that even possible?

JW: Puma concolor is the most efficient large predator in the Americas. They take prey down typically by crushing the windpipe. This strategy is not without risk of injury for the cats but works on animals big and small. They will take moose, but typically they prey upon deer and elk in North America.