Audubon of Kansas is suing the Kansas Department of Agriculture in state court in hopes of restoring Quivira National Wildlife Refuge’s water rights, the Topeka Capital-Journal reports. Quivira is a 22,135-acre refuge and relies on large, open ponds and impoundments to hold ducks, geese, swans, cranes, pelicans, egrets, plovers, and many other migratory bird species.

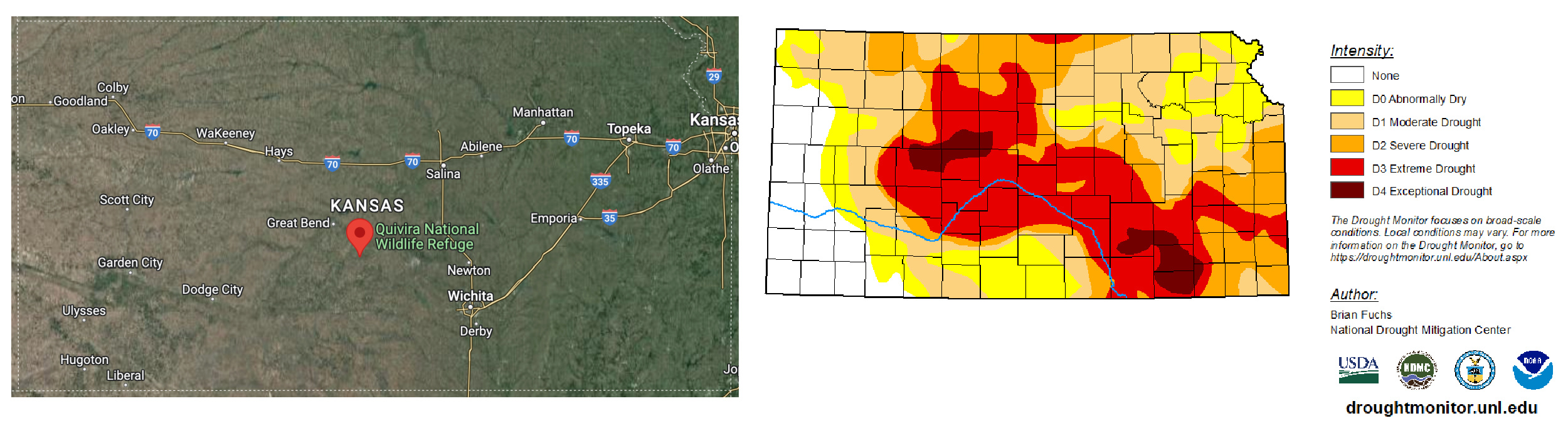

Quivira and its state-owned partner-in-habitat, nearby Cheyenne Bottoms Wildlife Area, combine to create one of the most beloved waterfowl hunting hotspots in the region. But as the Great Plains continue to deal with crippling drought, Kansas farmers working land upstream from Quivira are drawing water for irrigation—water that would otherwise go to the refuge. AOK argues that this overuse of water goes against state water law and notes that the issue has been going on for decades.

On January 15, 2021, AOK filed a lawsuit in a U.S. District Court against then-Secretary of the Interior David Bernhardt, then-director of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Aurelia Skipwith, and two officials from Kansas’ Department of Agriculture. In it, AOK claimed that these federal and state entities tasked with protecting and fulfilling Quivira NWR’s senior water right were failing to do so, allowing the Refuge to lose water to what they claimed were junior water right holders for over three decades.

Into the Depths of Kansas Water Law

Kansas water law follows the adage of “first in time, first in right,” a doctrine held by most Great Plains and Western states. In simple terms, whoever used water from a given surface or groundwater resource first (as of the start of statehood) holds the most senior water right. Enough water must exist for that user to get their fill—a set volume of water recorded with the state—before junior water right holders can divert water for themselves. In times of shortage, the “first in time, first in right” rule, otherwise known as the doctrine of prior appropriation, still applies.

According to the 2021 lawsuit, Quivira NWR holds a right to 14,632 acre-feet of water per year with a priority date of August 15, 1957, as well as a few additional water rights with priority dates before 1945. In total, they claimed the Refuge has a right to some 22,000 acre-feet annually. According to an investigation conducted in 2016 that was cited in the lawsuit, water users with junior rights are allegedly overusing from both the groundwater stores and the surface waters of the Rattlesnake Creek basin, costing the Refuge 30,000 to 60,000 acre-feet of water per year from 1995 to 2007. But junior users had been causing problems for longer than that too, the investigation found. The “impairment record,” as the lawsuit called it, went back 34 years. In 18 of those 34 years, junior water users cost the Refuge at least 3,000 acre-feet of water annually.

A federal appeals court threw out the lawsuit in May 2023, due to some procedural issues. But the lawsuit wasn’t exactly necessary anymore; in February, after years of negotiations with local landowners and government officials, FWS formally requested that the Kansas Department of Agriculture’s Division of Water Resources secure the water necessary to meet Quivira’s water right.

In April, chief engineer Earl Lewis responded to the request with a public letter explaining that any changes to water allocation in the basin wouldn’t be feasible until 2024 because the investigation from 2016, cited in the original lawsuit, needed updating. But AOK says that the KDA-DWR was dragging their feet in reviewing the FWS’ request. Enter the new lawsuit, filed in Shawnee County Court on July 11, which aims to compel the state to get the job done—without valuing junior water rights used mostly for irrigation over Quivira’s rights.

“If [the chief engineer] can decide which property rights to protect and which property rights not to protect, then our water law is effectively impotent,” Burke Griggs, AOK’s lawyer and professor at Washburn University School of Law, told the Capital-Journal. “And that’s not the way the law is built.”

Read Next: A Pacific Waterfowl Oasis Ran Out of Water. These Duck Hunters Are Footing the Bill for Some More

Drought continues to wrack Kansas and the Great Plains. The Ogalalla Aquifer is expected to go mostly dry within five decades. Average groundwater levels across western and central Kansas fell by over a foot in 2021 alone.

Ask any hydrologist and they’ll say that wetlands are crucial for ground and surface water retention. They act as sponges that hold water in the ground and suspended among root systems longer. They anchor soils and decrease the risk of flash flooding and subsequent erosion—not to mention the massive flocks of migratory birds they hold. Balancing these interests with Kansas’ reliance on agriculture, the second most fruitful industry in the state and the source of $17.6 billion in revenue in 2022, is tricky. But according to AOK, Quivira and the services it provides are worth their weight in water.

“If we talk about rural culture and sustaining rural communities, this is a real threat for the next generation,” Audubon of Kansas executive director Jackie Augustine told the Capital-Journal. “And I don’t want to be the one sitting by and saying, ‘Well, I could have done more.'”