Great Salt Lake waterfowl guide Chad Yamane has a single, simple imperative for his clients as tundra swans commit to his decoy spread, set their wide wings, and begin their long, graceful descent.

“When I give the word, I want you to shoot them in the yellow patch on their beak.”

But a few times every season, some hunter shoots the tail feathers off an incoming swan, and the bird either flies away or the hunter must make a quick adjustment and extend his lead for a follow-up shot.

“I can’t blame them,” Yamane says of whiffing swan hunters. “They see this 6-foot wingspan and 20-pound body coming at them, and they just aim for the chest. What they don’t realize is that the bird is much larger and flying much faster than they think, and so they shoot behind them.”

Everything about tundra swans and swan hunting is outsized, from the birds’ anatomy and their air speed to a hunter’s reaction when they hoist this snow-white trophy from the north.

“I’ve been on dozens of swan hunts, and I don’t ever get used to how big and beautiful and regal these birds are,” says Yamane, an Avery pro-staffer who guides for Utah-based Fried Feathers Outfitters when he’s not working as a battalion captain for the Salt Lake City Fire Department.

Because of their relative scarcity and magnificent appearance, tundra swans are one of the top trophy birds of the waterfowling world, right up there with king eiders and harlequin ducks. But unlike those short-migrating species, swans are thoughtful enough to come to us—or at least many of us—from their breeding grounds in the high Arctic. Swan seasons are open in eight states, ranging from Alaska, Montana, Nevada, and Utah in the Pacific Flyway, North and South Dakota (along with the eastern half of Montana) in the Central Flyway, and Virginia and North Carolina on the Eastern seaboard.

In every state where they are hunted, swans are treated as trophy birds. Hunting permits are distributed by lottery, the limit is one per season, and carcass tags are required to be validated after harvest, just as you might do for a deer or a moose. And most states require swan hunters to complete an orientation course to ensure they can distingish tundra swans from endangered trumpeter swans, which are often fellow travelers during the fall migration. (Trumpeters are larger than tundras, have a blockier head, and lack yellow on the lore, or fleshy patch, between the eye and the beak; the lore of a trumpeter swan is entirely black.)

Continental Abundance

Tundra swan numbers are increasing by a few percent every year. In a 2015 census, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimated there were about 117,000 tundras in the Eastern population and about 56,000 in the Western continental population, more than enough to support a regulated hunting season.

In Utah, the state’s Division of Wildlife Resources issues about 2,000 permits per year. Another 1,000 swan tags are distributed in Montana, and Nevada gives out around 600 annually. In the East, North Carolina has by far the most swan-hunting opportunity, issuing about 5,000 permits annually for hunts that take place between the Albemarle and Pamlico sounds. Virginia offers several hundred tundra swan tags, mainly for marshes along the Rappahannock River.

Pass-Shooting

At least in the West, the majority of swan hunters pass-shoot the birds. These hunters either don’t have specialized swan decoys or the boats and other gear required to hunt them on the water, or they have determined that intercepting pressured swans is a more effective strategy than trying to lure them into range on the big bodies of water they prefer.

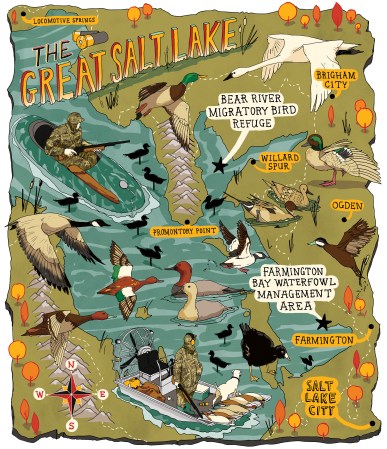

“Of the 2,000 swan permits Utah issues every year, I’d bet 1,500 are filled by pass-shooters,” says Yamane. These hunters line up on perimeter dikes and shoot swans as they fly between loafing and feeding areas in and around the Great Salt Lake’s Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge.

On Montana’s Freezeout Lake north of Great Falls, where several thousand swans stage every October on their south-bound migration, pass-shooting is legal, but sky-busting is discouraged. Hunters are required to have visible means of retrieval—a dog, a shallow-drafting boat, or chest waders—so the hunter can finish off and retrieve a swan that might not drop immediately.

It’s in pass-shooting scenarios that the size and speed of swans can be most problematic. The first time I hunted swans on Freezout Lake Wildlife Management Area, I did it with a borrowed 10-gauge and 3-inch BBB shotshells. When the first flock came over, I estimated their altitude at 50 yards and held on the lead bird. When I fired, the fifth bird in the line fell, stone-dead. How could I have misjudged the lead by so much? I had badly underestimated their size—they were probably closer to 60 or even 70 yards high—and their speed. Those slow wingstrokes disguised how much air they move; those birds were probably flying faster than 40 miles per hour. But I based my lead on the size and velocity of Canada geese, and counted myself lucky that I hadn’t crippled a bird.

Read Next: Duck Hunting The Great Salt Lake

Decoying

For the knee-knocking excitement of watching a giant bird commit from more than 100 yards away, there’s no equivalent experience in waterfowling to decoying tundra swans. Luring the big birds into a decoy spread is also the best way to deliver a killing shot with normal duck and goose payloads.

“I tell my clients to bring whatever they’re comfortable shooting for big ducks and geese,” says Yamane. “High-density No. 2 shot is pretty effective, and I’ve had plenty of one-shot kills with 20-gauges. The key is shot placement, and not getting seduced by that big body and instead aiming for that big black beak. You want to make a head and/or neck shot.”

Fried Feathers’ typical swan spread has about 60 decoys arranged in two groupings, with room between them for birds to land. Yamane sets up between swan loafing and feeding areas, and then runs traffic, calling to flocks of 30 to 50 birds.

“Those big, high-flying flocks are tough,” he says. “The smaller flocks with only one or two family groups decoy much better.” Yamane has experimented with a variety of swan dekes, but he says plastic Tanglefree floaters and V-board silhouette decoys are consistent producers.

“One thing we’ve noticed over time, especially hunting the shallow parts of the Great Salt Lake, is that decoys with erect heads aren’t as effective as decoys with the heads removed. If you watch real swan flocks, you’ll see that they spend most of their time with their heads down and their butts up, feeding. When we took the heads off our Tanglefree dekes, we found that swans finished much better in our spreads.”

In accordance with the size of the birds, a swan decoy arrangement needs to be more spacious than you might use for honkers.

“Swans need a big landing zone, so if you find they aren’t finishing, open up your spread,” advises Yamane. “Once they commit, you’ve usually got them. Then the main thing is to let them finish. And shoot them right in the yellow of their beak.”

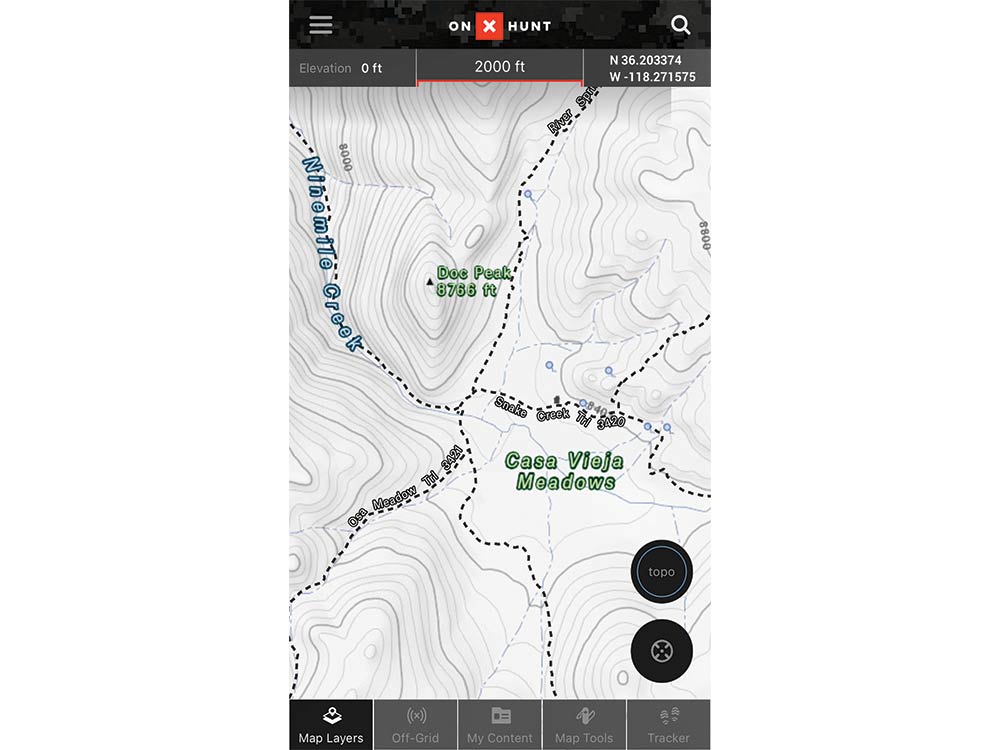

Maps on Your Phone

Migrating geese don’t read plat maps. They go where they find easy food, which is usually on private land. Because honkers can change their preferences based on wind direction and temperature, it’s hard for hunters to predict which field the geese will use from day to day.

The best tool in these moments is a detailed satellite map from onX (onxmaps.com), which you can pull up on your phone and provides the names of landowners. Find the geese, then find the name of the farmer who owns the field they’re using, make a call, and ask permission to hunt. The map certainly doesn’t guarantee access, but I’ve gotten permission from a number of landowners who didn’t mind if I hunted, as long as I didn’t drive in their fields.

New versions of the onX app have overlays that detail Boone and Crockett Club records by species and county for all 50 states, as well as a layer designed to appeal to backcountry hunters that shows parcels of land farthest away from roads, and even layers that show the perimeters and dates of wildfires and timber clear-cuts, so hunters can direct their attention to areas of emerging-forest growth.

Map packages range in price from $30 per year for layers that include public and private land boundaries (plus private landowner information) to up to $120 annually for a version that includes all layers available in the app as well as a state-specific map chip for GPS units.

Fool Swans with White Garbage Bags

If you don’t want to invest in specialized swan decoys, you can often get tundra swans to take a look at the next best thing: inflated white garbage bags that are anchored with enough weight to keep them in place but allows them to bob on the water.

These DIY decoys rarely get swans to come all the way in to the spread, but they often attract the attention of a passing flock, getting them to circle for a second look and bringing them nearer to the deck for a closer pass shot.

You don’t need many bags. A half dozen scattered on the outside edge of a dozen mallard decoys is a reliable ruse for unpressured swans. Dabbling ducks are typically found with swans, because as the big birds grub shallow marshes for food, they stir up crustaceans and vegetation, which the ducks then eat.