I’ve hunted in what’s now considered Wisconsin’s Northern Forest deer management zone on the same property for 24 consecutive gun seasons. My family and I have had some great hunts on our land, which consists of about 260 acres of popple, hardwoods, and beaver swamps. We don’t always kill big bucks, but that’s not really the point. The beer is always cold, the food and company are always good, and we always see enough deer to keep our sits interesting. But not this year. This season I hunted hard for two days and never saw a single deer. My family members saw very few deer as well. Opening morning, which often sounds like a warzone with rifle reports booming near and far, was eerily quiet. This experience didn’t feel nostalgic. It felt … discouraging.

Before long, I fled south to a different property that I hunt in the Central Farmland Zone where I saw deer on every sit and killed a few does for the freezer.

Anecdotes like mine have led Wisconsin legislators to propose a bill that would prohibit the Department of Natural Resources from issuing antlerless deer tags in 20 northern counties (including the county where my family property is located) for the next four years.

“We want to pump the brakes and stop killing does until we get a proper plan put together,” one of the bill’s authors, Representative Chanz Green, told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. “We’ve heard from hunters that we need to do something in the north.”

The concept here is pretty simple: Reduce the number of does being harvested in the fall and there will be more on the landscape in the spring to birth fawns. With more fawns on the ground, more will survive, and the deer population should increase. The proposal will certainly be popular among some Northwoods deer hunters, many of whom are not interested in shooting does anyway. But hopefully the “proper plan” Green mentions is about establishing a more comprehensive strategy for the Northwoods, because simply halting doe harvests probably isn’t going to save deer hunting here. That’s because deer populations fluctuate based on a variety of factors, including predators, winter severity, and quality of habitat.

Understanding the Decline

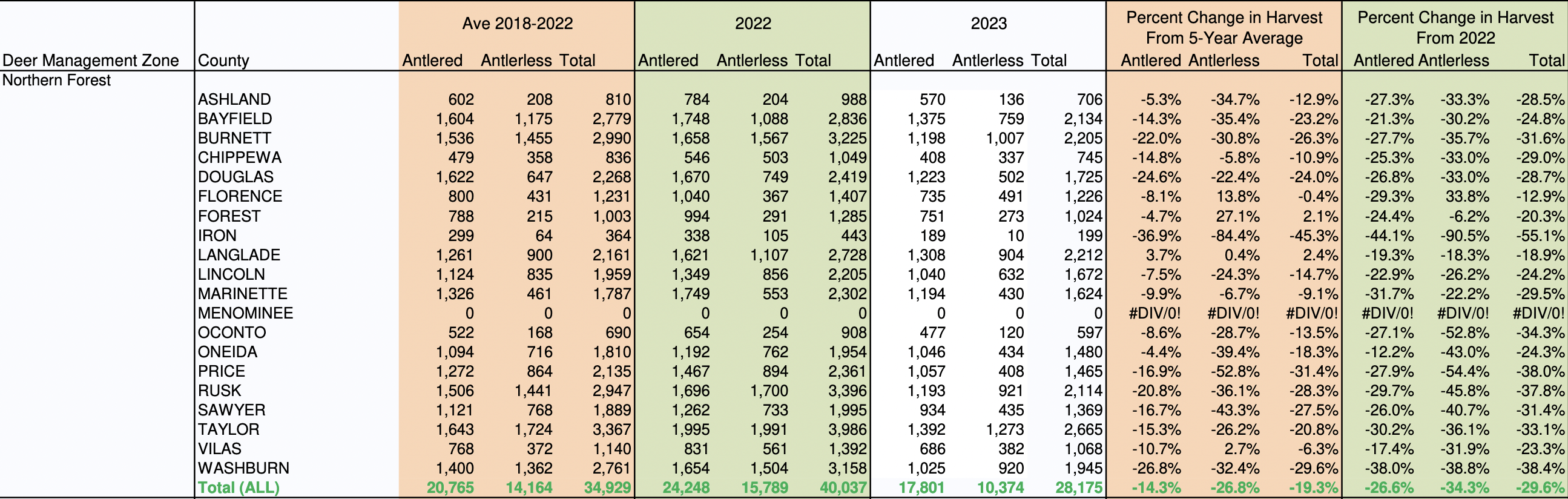

The harvest numbers back up Northwoods hunters’ complaints about slow seasons. According to 2023 harvest data, the Northern Forest kill of 28,020 total deer was down 30 percent from the previous season and down 19 percent from the five-year average.

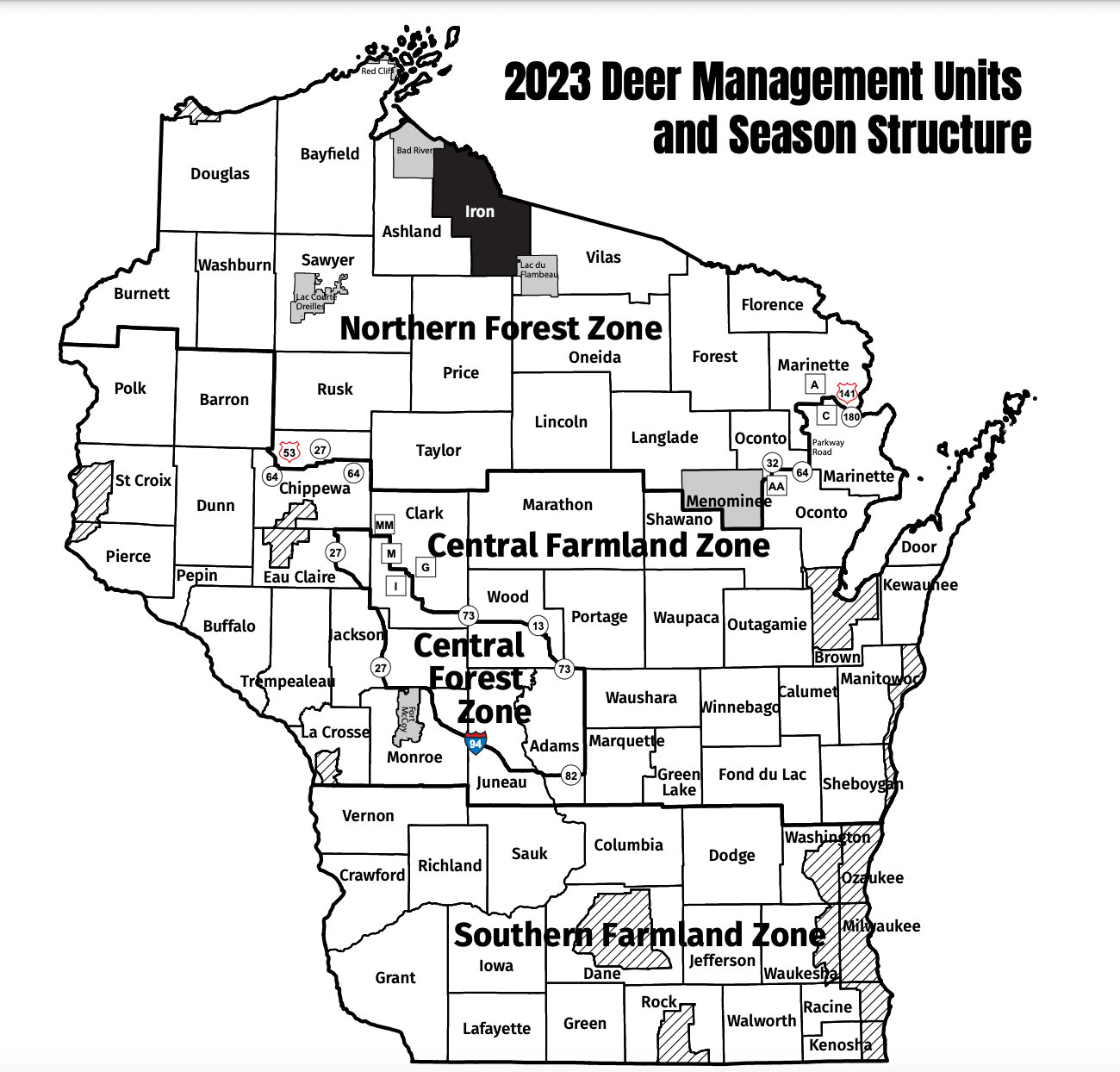

As you can see in the map below, the Northern Forest Zone encompasses 20 counties in about the top third of the state. For reference, the Southern Farmland Zone covers a smaller huntable area but hunters in that region harvested a total of 41,692 deer. In other words, relatively few deer are being killed in the large expanse of Wisconsin’s Northwoods, where most of our public land is. This Northern region accounted for only 16 percent of the total harvest in 2023.

Wisconsin DNR

Similar harvest declines can be seen in northern Minnesota and Michigan, as Pat Durkin reported for Outdoor Life in 2022. Northeastern Minnesota’s buck harvest declined 57 percent over the past decade. The Michigan DNR, meanwhile, documented a declining buck kill for 35 years in the Upper Peninsula. It sank to about 24,000 in 2009, rebounded to about 35,000 in 2012, and then crashed to about 17,000 in 2014. The buck harvest then rose to 30,000 in 2017 and 2018, before falling back to about 25,000 in 2019, according to Durkin’s reporting.

Talk to any veteran Northwoods hunter and they’ll tell you about glory days in the early 2000s, when everyone saw plenty of deer and the pickup trucks heading back south on Highway 51 would be stacked full of bucks and does. So, what happened?

The Problem Is Wolves, Right?

On social media pages and forums, threads about this proposal are flooded with commentary about wolves. Most comments read something like: “Oh great, there will be more does for the wolves to eat.” (At least those that aren’t espousing conspiracy theories.)

There’s no doubt that wolves take their share of whitetails, especially fawns, and under federal protections, state DNRs are currently unable to implement wolf management plans (wolf hunting or trapping) even if they wanted to. There are an estimated 1,007 wolves in Wisconsin.

Interestingly, while wolves are by far the most controversial predator species in the state, they might not be the most influential one when it comes to deer populations. According to Durkin’s reporting, fawns get hit hardest by wolves and black bears in Minnesota, bears and bobcats in Wisconsin, and coyotes and bears in the U.P.

There are more than 24,000 bears in Wisconsin, with most of them living in the northern half of the state. The bear population has risen dramatically from the 1980s until recent years, dipping only slightly.

What’s much less fun to rage about on internet forums is winter severity or the nuances of Northwoods habitat. The state keeps a Winter Severity Index report which tracks how brutal (or mild) the winters are annually. Even when most of the state has a mild winter, northern counties can see conditions that stress the deer herd. As an example, during the 2022-2023 winter, eight northern counties had a “severe” or “very severe” winter while the entire rest of the state had a “moderate” to “mild” winter. Most deer managers will point to the brutal 2013 winter, which brought large winter kills across much of the North.

Deer herds tend to rebound more slowly in the North where habitat management is more nuanced. There are few large cornfields full of waste grain in this region.

“[Northern deer] need balanced habitat with enough mature conifer cover and dense canopies that block deep snow and give deer room to outrun wolves,” retired wildlife manager Tom Rusch told OL in 2022. “Ideally the deer will also be within reach of good food. Yes, deer need edge cover and young growth, but if [logging projects] cut too much, too fast and leave little mature forest, deer pack into small areas and become sitting ducks. That’s when wolves can run them down in little snow.”

There are a lot of important details to consider in Northwoods forest management. Within mature Northern forests, deer rely on dead or dying balsam fir, which generate a nutritious lichen. Plus, deer can suffer when popple (what we call aspen in Wisconsin) stands get cut too soon. Young cuts provide great food seasonally, but they provide little winter cover. Deer need a good combination of young stands for food and mature woods for cover.

Why It Matters

Wisconsin DNR

There are some real downsides to a blanket ban on harvesting does. Yes, it will put more deer on the landscape temporarily, but it will also prevent private landowners from managing their herds. Of the 10,374 antlerless deer that were harvested in the North in 2023, about half of them were taken in only five counties. Landowners in those counties would only be able to watch does as they feed in their cornfields or food plots.

Meat hunters will likely be more willing to shoot young bucks. And Wisconsin is already one of the worst states in the country at letting young bucks walk.

Currently, County Deer Advisory Councils make recommendations on the number of antlerless tags that should be issued for their county. In general, the best deer management practices are the most specific ones. We need to manage herds at the property level, not the regional level. But I fully agree that more aggressive management steps should be taken to sustain deer hunting in the Northwoods. It’s one of the last places in the Midwest to experience wilderness hunting. It’s also home to huge tracts of public land and countless traditional family deer camps (like mine) on small patches of private land.

If folks stop heading “up north” to go deer hunting, what we’ll be left with is crowded public ground down south or private hunting on large tracts of land that only few can afford. That would be a sad state of Wisconsin deer hunting, indeed.

Today is the deadline for Green’s bill to earn cosponsors, then it will head off to legislative committees. From there, who knows what will happen.

But here’s one Northwoods hunter’s opinion: If we’re going to prohibit doe harvests in order to save deer hunting in the North, so be it. But then we must also do the even more important work of improving and conserving our forests and managing predators. Otherwise this proposal will result only in fewer opportunities for Wisconsin deer hunters.