It’s become an almost regular occurrence for a “hunting celebrity” to get busted breaking game laws each fall. They post their violations to social media or showcase the hunts on outdoor TV—exactly the platforms that federal agents watch, waiting for them to make such a blunder. Any unethical hunter can end up in this kind of jackpot, but it’s the celebrity cases that draw the most attention, because, well, they are inherently attention-seekers.

Hunters Josh and Sarah Bowmar are a few of the more recent hunting personalities charged with violations, joining the ranks of Spook Spann, Chris Brackett, and a host of others (though the Bowmars have not yet been convicted of any wrongdoing). Deer and Deer Hunting reported in late October that the Bowmars had been indicted by a federal grand jury, but the case circulated on various social media channels months prior to that. You might remember the Bowmars from the notorious Alberta bear hunt that led the province to outlaw bear hunting with a spear. In this case, they are being charged with knowingly transporting, attempting to transport, receive and acquire wildlife, including turkey, deer or parts thereof, in interstate commerce, according to the Grand Jury indictment.

Often, these types of charges become a federal matter, due to a myriad of laws that fall under the Lacey Act. Signed in 1900 by President William McKinley, the Lacey Act protects plants, fish, and animals by civilly and criminally penalizing those who violate its provisions. It also prohibits the importation of invasive or harmful species, or their introduction to the environment (for example, zebra mussels into lakes and rivers).

The Bowmar’s lawyer, G. Kline Preston, is challenging the legality of the more than 100-year-old Lacey Act. In a public statement, Preston said his clients were innocent of all charges and also stated that the Lacey Act was “abusive” and “draconian,” and that it excessively punished hunters for minor infractions. Kline also stated that the Lacey Act is used too often against hunters for “actions which really amount to the equivalent of a speeding ticket.”

“I believe that the federal penalty scheme of the Lacey Act is not commensurate with the fines and incarceration times that violations of the Lacey Act entail,” Preston wrote to Outdoor Life in an email. “I also believe that the legislative framework of the Lacey Act violates the 10th Amendment. We do not admit any of the facts alleged in the indictments against the Bowmars. The Bowmars have entered pleas of not guilty as to all charges.

“I intend to challenge the constitutionality of [the Lacey Act]. I realize it is a big challenge. It is definitely a ‘windmill’ and perhaps I will be a Don Quixote. But, keep in mind that segregation was once found to be constitutional and later unconstitutional by our Supreme Court who interpreted the issue based on the same document—the U.S. Constitution. It is time that the Lacey Act be challenged again.”

What Is the Lacey Act?

There are several very specific laws that fall under the Lacey Act, and if you want to understand them all, read this document published by the USFWS office of law enforcement. It details Lacey Act violations and penalties. You can be prosecuted for transporting specific species of plants, wild-game, and non-wild game animals. From 2017 to 2019 there were 5,087 Lacey Act cases, and there have been another 1,746 so far in 2020, according to a USFWS report.

The most common way Lacey Act law is broken is when a poacher kills an animal, and transports that animal across state lines or brings the animal into the U.S. illegally. The poaching of that animal is a state case (unless the game has federal protections, like migratory birds). But as soon as the poacher crosses state lines, the provisions of the Lacey Act make it a federal crime.

“The Lacey Act is triggered when a violation of state law occurs [the illegal take of an animal] and the animal is transported across state lines,” says Christina M. Meister, a public affairs specialist for USFWS. “A violation also occurs on federal land when the animal is transported from the site of the violation; or a guide service is involved in violation of state or federal laws during a hunt.”

Now, you don’t have to drive or fly an illegally-taken animal across state lines for it to be a violation of the Lacey Act. You can also be charged if you kill game illegally on federal land, or a Native American reservation, and transport that animal out of either of those areas. For example, say a poacher kills 10 mallards in a National Wildlife Refuge, gets in his truck, and drives home. Not only is shooting more than a limit of ducks a violation of the Migratory Bird Act, but it also violates the Lacey Act because he shot those ducks on federal ground and and transported it across that boundary when he drove home.

You can also violate the Lacey Act by hunting with an unlicensed outfitter in a state that requires guides to be licensed. And it doesn’t matter if you didn’t know the outfitter needed to be licensed—ignorance does not hinder prosecution. So, check state laws. If they require an outfitter’s license, ask your guide to provide one before booking the trip and keep a copy or picture of it on file. Even if you think you legally killed an animal, if that outfitter wasn’t licensed, once that bull or buck crosses state lines, you have committed a federal crime, and you can be charged.

RELATED: The Time I Hunted with a Waterfowl Poacher (and Didn’t Know It)

Same goes if you pay a licensed outfitter, but you don’t have a tag in your pocket. That act itself is a violation of the Lacey Act because you are exchanging money to shoot wild game illegally. Transport that animal across state lines, and it’s another charge.

Unlawful party hunting, which is when hunters shoot other hunters’ game to fill tags or limits, can also land you in trouble. Every hunter is responsible for killing their own animal and properly tagging it. (You need to keep your animals tagged crossing state lines as well to ensure you’re legal.) For example, if you’re elk hunting with four buddies and you all have tags, that means each one of you can kill one bull or cow, depending on the tag. If a hunter in your party shoots two bulls and puts someone else’s tag on the elk he or she shot, and then transports it across state lines, it becomes a Lacey Act violation. That’s exactly what “Fear No Evil” TV host Chris Brackett was pinched for when he shot two Indiana whitetail bucks on the same morning. He killed one, and then a bigger buck stepped out, and he shot that one too. Then Brackett secured a buck tag for his cameraman in order to separately tag both bucks, and drove home to Illinois—a Lacey Act violation that ended up costing him almost $30,000 and his TV career.

“You need to familiarize yourself with the laws of the state you are hunting before you go,” says Dennis Cease, chief of law enforcement for Wyoming State Parks and a big game and turkey guide. “You have to do your due diligence and make sure the outfitter you go with is properly licensed [if the state requires it], and what the transportation and tagging laws are in that state. Don’t, and you could be charged with a federal crime whether it’s an honest mistake or you’re breaking the law deliberately.

“It’s really up to the hunter to have enough moral character, because I’ve seen people easily be swayed to go over the line,” says Cease, who also worked as an undercover wildlife agent. “There are some outfitters that will say ‘give me X amount of dollars and you can shoot another one [without a tag].’”

Ignorance Won’t Save You from Prosecution

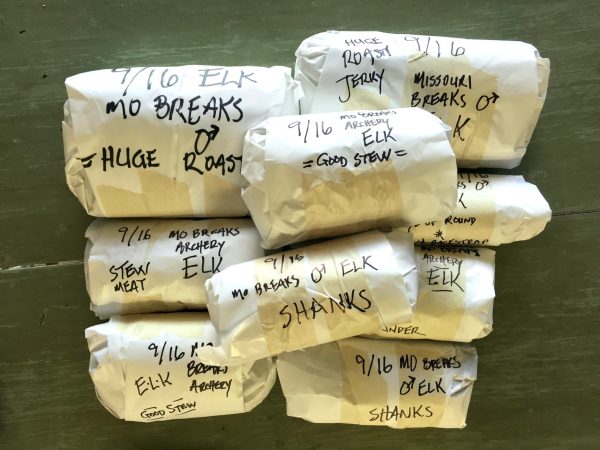

This may seem unfair, but if you unknowingly accept wild game meat from someone who killed an animal illegally, you can be prosecuted under the Lacey Act. How do you avoid this? Ask to see the hunter’s tag and license. It’s up to you to make sure all the paperwork is in order before you accept the meat. The penalty likely would not be as stiff for you, but you are still breaking the law no matter how legit the transaction may seem.

One penalty that is much stiffer is if you unknowingly transport illegally-taken game across state lines. Say you and a buddy road trip in your truck for an antelope hunt and he shoots a buck without a tag, but doesn’t tell you he isn’t properly licensed. Once you drive that animal across state lines, it becomes a Lacey Act violation. And under the law, any vehicle (or mode of transportation) used to transport that illegally-killed animal can be seized by the federal government. So, if you don’t want to lose your truck, make sure all your friends are compliant with the law. This may seem like overkill, because you have the expectation your friends wouldn’t hunt illegally, but it’s smart to make sure everyone is following the law, particularly when you’re doing the driving.

Also note that certain states (particularly in the Midwest) have Chronic Wasting Disease laws where you must check in your kill for testing and/or are not allowed to transport certain parts of an animal. If you break either or both of those laws and drive the animal across state lines, you are breaking Lacey Act law.

What Does the Lacey Act Actually Do?

The civil penalty for breaking Lacey Act law can cost you up to $10,000 per offense. Criminal penalties may result in up to a $20,000 fine and five years in prison. The federal government can also seize any property used in committing the crimes, plus you can have your hunting license revoked for an amount of time determined by a federal judge. If you’re an outfitter, the judge can suspend your license to operate (thus taking away your livelihood) for a very long time.

These laws are in place to deter folks from poaching game, introducing non-native species into our environment, and to prevent the spread of animal disease, like CWD. That ensures our wild game populations remain sustainable, and why the Lacey Act continues to be relevant after more than 100 years. Without these laws, the fines for illegally killing wild game would be lower, which could cause more poachers to unabashedly kill wild animals without fear of steep financial ramifications. We would likely see more invasive species taking root in our hunting and lands, and animal diseases could spike.

The original purpose of the Lacey Act was passed to stop the mass killing of wildlife populations that occurred during the market-hunting era. It outlawed the interstate shipment of illegally-killed wild game, and also the killing of birds for the sale of their feathers. There have been a handful of amendments to the Lacey Act since its inception, the most recent of which came in 2008, and included timber and plants. Gibson Guitars and Lumber Liquidators are two of the most highly publicized cases for trafficking in illegal lumber. The fines against Lumber Liquidators totaled more than $13 million.

“The most important aspect of the Lacey Act for hunters is to hunt responsibly and to know all rules and regulations,” Meister says. “No matter if you are a new hunter or have been hunting for years, you should know all local, state, and federal laws that pertain to the hunt you are participating in. Additionally, a hunter should check to see if the states they might be traveling through with their game have any restrictions.”

Read Next: 9 Migratory Bird Laws You Didn’t Know

Is It Too Strict?

There is an argument to be made that the Lacey Act is too harsh on those who unknowingly violate it. For example, in 2016 a Mississippi hunter traveled to Texas for a whitetail hunt. He killed a deer and had the outfitter mail it from the ranch in Texas to his home in Mississippi. But Mississippi does not allow the importation of whitetails to the state. So, both the outfitter and client were found guilty of violating the Lacey Act and sentenced to three years probation and a $10,000 fine.

“I don’t think that’s fair,” says one hunting guide, who asked not to be identified. “As a client, you have certain expectations that the outfitter is not breaking the law. And the outfitter wasn’t trying to do anything wrong, he just didn’t know the rules. He was only trying to do right by the client, and get him the meat, hide, and skull. I guess he paid a hefty price tag for it.”

But when G. Kline Preston compares Lacey Act punishments a speeding ticket, that seems a bit extreme. The physical transportation of illegally killed animals across state lines or off of federal property may seem like a small infraction, but the laws against it have kept wildlife on the landscape for more than a century. Without the Lacey Act, there would assuredly be far fewer critters in the woods and wetlands.

“The Lacey Act is a tool for state and federal law enforcement to work together in the conservation of wild populations,” Meister says. “It enables agencies to investigate a state hunting violation and encompasses multiple states. However, this is a small piece of the sustainability of wild game populations since it takes good game management practices and voluntary compliance from hunters to help the population and species thrive for the future.”