AS SOON AS Hashbrown launches from his arm, Tyler Sladen starts running. I follow, sprinting through the soft New Mexican sand, dodging cholla cactus and piles of trash, and trying not to lose sight of hawk or hunter. I can mostly keep up with Sladen, a 27-year-old Army veteran accustomed to running at high altitude. But Hashbrown is a different beast. In the time it takes the juvenile northern goshawk to soar half a mile across the hills, we’ve barely covered 80 yards. In the distance, Sladen’s buddy Kevin Jackson works their combined pack of setters, still combing the brush for quail.

We’re hunting a chunk of public land on the outskirts of Albuquerque. It’s an off-roading hotspot and a dumping ground for everything from one-eyed dolls to toilet seats. The place holds quail and rabbits, though, and there’s little competition for game since it’s illegal to discharge a firearm here. But that doesn’t mean we don’t hear gunshots nearby.

When we do reach Hashbrown, he’s perched on the highest bush around, a vantage point from which to watch for game while waiting for Sladen to collect him. Beside the sage sits Trigger, a 4-year-old Vizsla and the hawk’s devoted bodyguard.

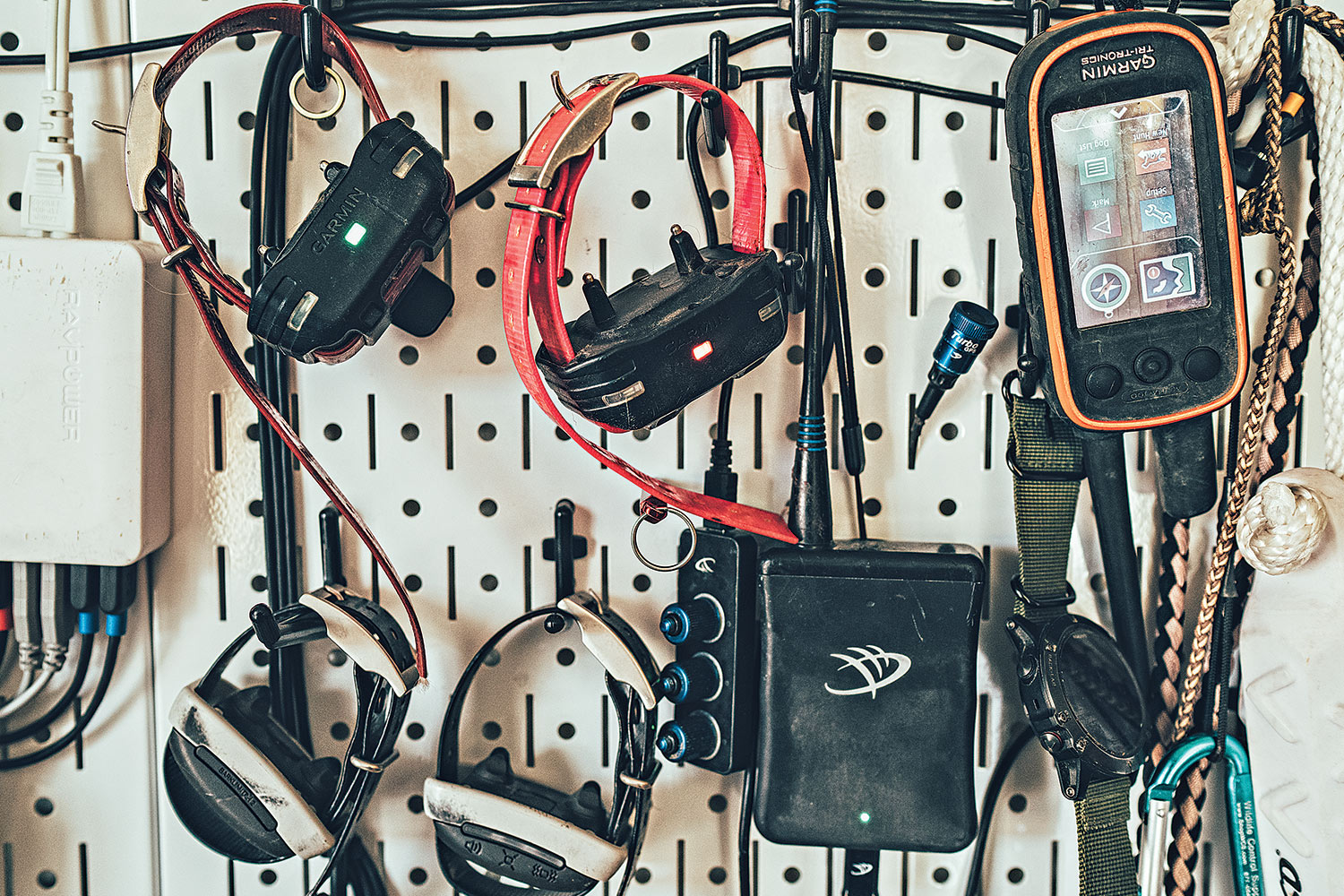

Vizslas were historically bred as Hungarian falconry dogs, and he, at least, can keep up with Hashbrown. When Hashbrown takes off in pursuit of quail, Trigger does the grunt work on the ground, re-flushing birds that try to hide in the brush and standing guard whenever the hawk makes a kill. Birds of prey, especially young ones, are vulnerable to all kinds of hazards, including other people’s dogs, windows, and cars. They’re also in danger from coyotes, sometimes attracted by the distress squeals of the dying rabbits he catches. For now, though, all is calm. Sladen raises a gloved arm, and Hashbrown hops neatly onto the offered wrist.

“Falconry is kind of like a dragon that you’ll continuously chase to make everything perfect,” he says. “Perfect for me is different than perfect for someone else. Honestly, my ideal falconry would be to have all my dogs working harmoniously, finding birds, backing and honoring, and pointing a bird. I’d walk in and flush that bird. And Hashbrown would catch it off the initial flush. The amount of times it goes like that? Not often. [But] if I wanted to stack tailgates [with birds], I would just pack a gun.”

The hawk combs a curved beak through his feathers before peering around again, head on a swivel. The desert cottontail he’d flown after escaped down a hole, but there’s plenty more game to be found. Birds miss, just like human hunters, and this is Hashbrown’s first season. It’s a critical training period for the juvenile hawk, and one that demands much of Sladen’s free time.

“I’ve been with that bird every single day [since I got him],” Sladen says, whose job in nuisance wildlife control gives him a flexible schedule. “If you want to do falconry at this level, it’s not something you can just wake up and do.”

In early 2019, Sladen drew one of New Mexico’s six goshawk tags, which allowed him to legally collect and possess a wild raptor. All of April, May, and most of June, he scouted for a nest in the mountains. After locating a nest of the correct species, Sladen still had to reach it.

“Climbing the tree can be the easiest thing in the world, or it can be absolutely terrifying if you’ve never done it before,” Sladen says of pulling the chick. “To get attacked by a pair of birds [protecting their young] while you’re dangling 80 feet in a tree, and they’re drawing blood in a way that hurts? It’s not something you can really be prepared for. It’s just something you’ve got to go through.”

This is a rite of passage, and a major time commitment, which many falconers don’t even attempt, choosing instead to buy birds from breeders or capture adults and release them at the end of the season. In 2019, Sladen and his buddy were the only two New Mexico hunters who filled their tags.

When he brought the goshawk chick home, though, that’s when the work really started.

We teamed up with Project Upland for this story, which originally ran as “Prey Drive” in the Fall 2020 issue. Check out the feature film from our hunt or read more OL+ stories.