We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

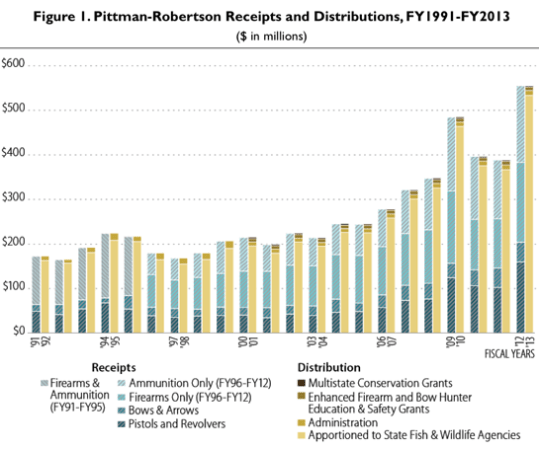

It’s rare to find Americans who are thrilled to pay their taxes, but hunters and gun owners have been uncommonly proud to pay excise taxes on guns and ammunition for the better part of a century. Now those excise taxes—which contributed more than $1 billion to conservation funding in 2021 alone—have become the target of a new bill that seeks to repeal parts of the Pittman-Robertson Act.

Last week Andrew Clyde (R-GA) introduced the RETURN (Repealing Excise Tax on Unalienable Rights Now) our Constitutional Rights Act to eliminate the 11 percent federal excise tax on firearms and ammunition that funds conservation in America. Clyde’s argument is that the excise taxes on firearms and ammunition threaten Second Amendment rights.

“If the government can tax an individual’s constitutional right, then it’s not really a right at all,” reads an opinion piece posted to Clyde’s website. The bill was introduced with support from more than 50 Republican representatives.

Why We Need Excise Taxes on Firearms and Ammo

The bill has been met with opposition and confusion from the hunting and conservation community.

“The irony of this whole thing—to say it’s unconstitutional to tax something that is a stated right in the Constitution—is that hunters asked for [the Pittman-Robertson Act] in the 1930s, and have loved it ever since,” says Whit Fosburgh, president and CEO of the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership. Fosburgh notes that excise taxes have helped the shooting sports and hunting industries grow: They’ve paid for shooting ranges, hunter education programs, wildlife management, and habitat restoration. “You name it, stuff that we [hunters and gun owners] care about has been funded by this. The notion that it’s somehow an infringement on rights is absolutely ludicrous.”

Clyde says the RETURN act is a response to a Democrat-sponsored bill that seeks to impose a 1,000 percent excise tax on AR-style rifles and magazines that hold more than 10 rounds. But rumors of an attempt to eliminate these excise taxes have been brewing well before the “Assault Weapons Excise Tax” was unveiled. That’s why in May—a full month before both bills were introduced—43 hunting, conservation, and gun rights groups signed a letter opposing changes to excise taxes on guns and ammunition.

“We are united in our shared support for the current ‘user pays-public benefits’ system of wildlife funding,” reads the letter, whose signers include the National Rifle Association and the National Shooting Sports Foundation. “Among other things, generating all Pittman-Robertson funding from alternative sources would negatively impact our community’s unique relationship with state fish and wildlife agencies. Without the financial contributions of sportsmen and women and sporting manufacturers, the seat held at the decision-making table for hunters and recreational shooters may be lost.”

The letter emphasizes that Pittman-Robertson dollars have generated $15 billion for conservation since it was enacted in 1937. Clyde’s bill proposes replacing this lost conservation funding with offshore oil and gas taxes, similar to the Land and Water Conservation Fund.

“The offset he’s looking to justify his bill [with] is a little bit laughable, and naïve given that so many other existing funding mechanisms rely on offshore oil and gas revenues,” says John Gale, conservation director for Backcountry Hunters and Anglers, another organization that signed the letter in May. “Those are market-based revenues that depend on consistency … offshore oil and gas revenues are the opposite of dependable. You see dips and spikes there. And as our energy portfolio becomes more diverse and includes more renewable energy development, those Outer Continental Shelf dollars are likely to decline down the road, not necessarily increase, to meet even the current demands—let alone the future demands—states will have for their wildlife budgets.”

Under the current framework, states must match incoming P-R dollars with $1 for every $3 received. That state money typically comes from hunting license dollars. The existing system ensures that states are incentivized not to divert their hunting license funds toward things like road construction projects or correctional facilities.

Plus, if a state wanted to sell off one of its wildlife areas—which was originally paid in part with P-R dollars—that would be considered a diversion of federal aid, and the state would have to pay back those P-R dollars to the federal government.

“P-R dollars are a carrot and a stick, because the feds can actually go and claw back the money they’ve given states in the past [if states divert hunting license dollars],” Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation’s director of government affairs Ryan Bronson told Outdoor Life last year. “The P-R Act protects those dollars better than almost anything else. You can raid almost anything in an emergency, but you can’t with game and fish dollars.”

“An attempt to pander to gun owners”

Without excise taxes on guns and ammo, funding state wildlife agencies would require taxing all Americans—not just gun owners. Curiously, Clyde’s bill also seeks to eliminate similar excise taxes on archery gear, fishing tackle, and boating equipment. Gale suspects Clyde is attempting to eliminate excise taxes on all sporting goods while leveraging the Second Amendment to garner public support.

“Because Congress has been working through deals on some type of modest gun legislation, [Clyde’s] trying to shoehorn in on it by attempting to make his bill about 2A,” says Gale. “But what it really does is become maybe the most significant threat to wildlife conservation we’ve faced in a long time, given how much money that Pittman-Robertson directs to state wildlife agencies … The [gun] companies that contribute to it have never asked for this [RETURN] legislation. They’ve never balked at Pittman-Robertson.”

P-R taxes are applied to manufacturers who then bake them into the cost of their goods. In other words, although consumers aren’t technically paying the tax, they are ultimately footing the bill. So even if the tax was eliminated, consumers wouldn’t necessarily see a price reduction at the register, since the cost of firearms and ammunition are dependent on a wide variety of factors (including availability and price of materials).

“This is a terribly misguided piece of legislation,” says Mark Oliva, managing director of public affairs for NSSF. “The firearm industry is proud that it has generated over $15 billion for wildlife conservation since the Pittman-Robertson excise tax was enacted … The fact is, the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation is the envy of the world and that’s been made possible because of the investments made by firearm and ammunition manufacturers.”

Fosburgh calls the RETURN act an attempt to pander to gun owners by legislators who don’t really understand how that wildlife funding works.

“It makes no sense whatsoever,” says Fosburgh. “This is a badly written bill. People are playing politics here and they’re trying to do something good for gun owners but is in reality bad for gun owners. And it’s really bad for hunters.”

On the bright side for the sporting community, the RETURN our Constitutional Rights Act has “zero chance” of passing this Congress. It hasn’t had a hearing or markup, says Gale, and would need to go through more formal steps before coming close to passing. The danger lies in the fact that many legislators don’t seem to understand how conservation is funded in America, and the bill could potentially rear its head in a future Congress.

“If this bill somehow got enough support to pass one day in a crazy future world, it would pull the rug out of the most substantial and dependable funding mechanism that state agencies have relied on for a long time,” Gale says. “Where’s that burden going to be shifted to? Who’s going to pay for that bill? There’s just no one there. There’s absolutely zero thought into a bill like this.”

This story was updated on July 1, 2022 to include comment from the NSSF.