As the snow melts and temperatures climb, spring turkey seasons across the country are starting to open. In some regions like the Upper Midwest, wild turkey populations seem healthy. In others, especially the Southeast, an ongoing turkey population decline has many hunters worried.

Game agencies can’t actually count the number of turkeys in their state, which is part of the problem—we don’t know precisely how many turkeys we have and or dramatic the population declines really are. But based on rough population estimates and hunter harvest reports we know that populations are trending downward in much of turkey country. Hunters and biologists are reporting reduced gobbling, fewer birds on the landscape, and shockingly low poult counts.

As these troubles continue to creep from state to state, the real question is, why?

The Factors of a Population Decline

Renowned turkey biologist and hunter Dr. Mike Chamberlain says there are a variety of factors contributing to turkey population declines. In the East, key issues include habitat loss and degradation, an increase in predators, and, yes, hunting pressure.

But as Chamberlain notes, this drop isn’t limited to the Southeast. New York Department of Environmental Conservation wildlife biologist Josh Stiller highlights recent, localized declines in western New York. (The statewide population has been relatively stable since a serious statewide decline in the 2000s.)

“There are many hypotheses for why turkey populations have declined,” Stiller says, listing them off. They include:

- A natural “contraction” after reintroduction and historic high populations. (In other words, hunters were spoiled by unsustainably high turkey numbers in decades past; the population densities we see now could be the new normal.)

- Higher predation of nests and poults.

- Declining habitat quality, including changing agricultural practices.

Chamberlain says that hunters should think about turkey population dynamics like a football team. Each important factor is a different position. Brood rearing habitat would be the quarterback, for example. Predator suppression might be the kicker. In some games (or regions for this metaphor), certain positions matter more than others. But in order to win a game, every position needs to work together.

“Right now, we’re losing more than we’re winning,” Chamberlain says.

Low Poult Production

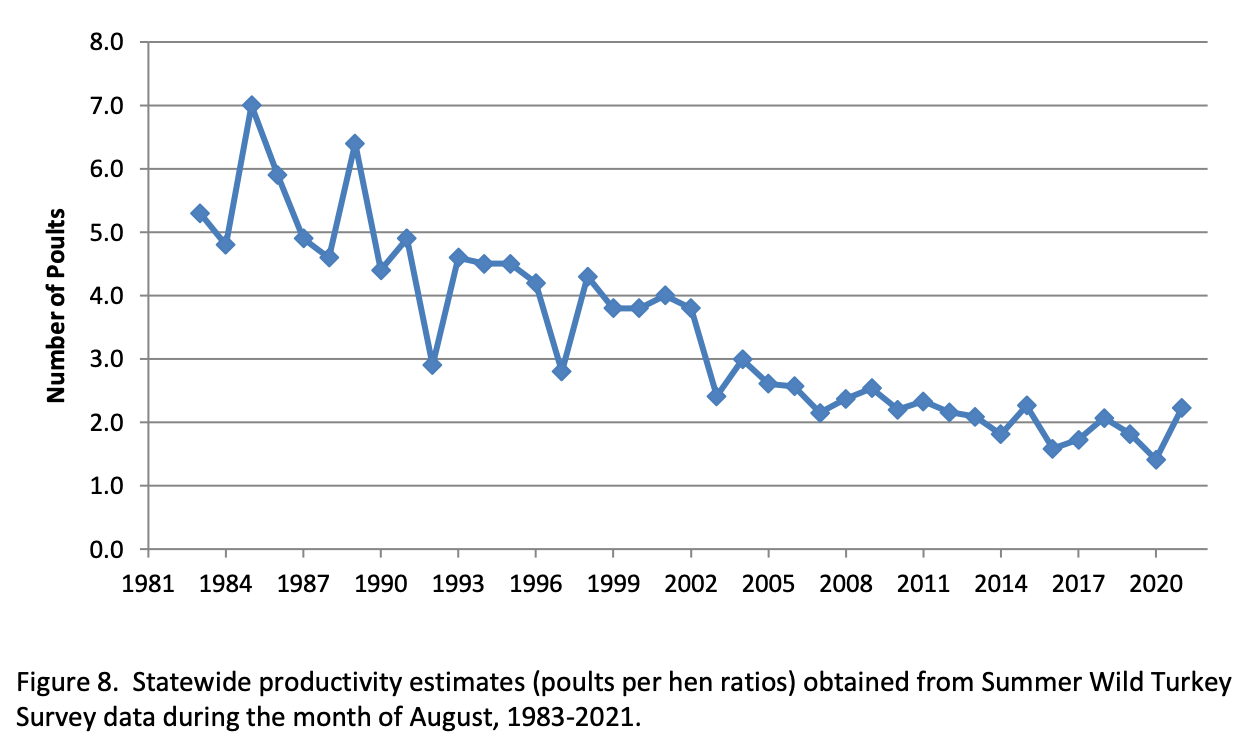

When Chamberlain delivered his “State of the Turkey” address at the National Wild Turkey Federation’s 2022 Rendezvous, he showed a collection of 12 graphs on a single slide. Each graph represented a state in the Southeast, and each trend line represented the state’s poult-per-hen ratio over the last two to five decades. All 12 trend lines sloped downward.

“There’s no question that birds are struggling in some areas, particularly in the Southeast and parts of the Midwest,” Chamberlain tells Outdoor Life. “The research has clearly shown that [turkeys] are just not as productive as they were a few decades ago. We’re not making as many young turkeys as we were.”

Why are turkey poults struggling to survive? It starts with nesting habitat and brood rearing habitat.

“We’ve essentially created ideal predator habitat in a lot of wild turkey range,” he says. “We’ve fragmented forest, we’ve converted forest from hardwoods to pine, we’ve removed habitat for urbanization and development, so if you look at the United States now versus 20 years ago, it’s just not as ‘good’ as it [used to be] for turkeys.”

Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency turkey program coordinator Roger Shields confirmed that the state’s poult production has struggled in recent years, matching the regional trend. This is especially true in the Mississippi River corridor, where flooding has submerged large tracts of habitat. After several years of flooding and habitat lost to urbanization, the poult-per-hen ratio dropped to a record low of 1.4 in August 2020, according to the TWRA’s 2021 Annual Wild Turkey Status Report. In other words, by August that year hens had an average of only 1.4 surviving poults. The long-term average since 1983 is 3.4 poults per hen.

“The 2020 reproductive year was pretty dismal,” Shields tells Outdoor Life. “That didn’t help things.”

In order for nests to survive and for poults to see their first year, nothing is more crucial than quality habitat that turkeys can use to survive predation, Chamberlain says.

“The percentage of nests that are hatching is simply lower than it has been historically. The nests are being destroyed and most nests fail, that’s the bottom line,” he says. “The percentage that do hatch in some of our areas is literally below 20 percent, and in others it can be 25 percent, but … the primary cause of failure is predation of the female [or] the eggs themselves … The other thing we’re seeing is that once they hatch, poult survival or brood survival seems to be very low. There’s an overwhelming lack of brood habitat in many areas.”

Predators in Poor Habitat

Decades of research shows that predation is the primary cause of nesting failure in wild turkey populations—a fact Chamberlain cites in a recent study on turkey nest predators in Louisiana. In the study, feral pigs, armadillos, coyotes, opossums, crows, raccoons, bobcats, and foxes all preyed on nests. The abundance of these predators was dependent on the types of habitat the nests were in. In other words, nests closer to water suffered more harassment from raccoons while coyotes were more common in burned areas.

On first glance, hardwoods with thick undergrowth might seem like the perfect place for a brood of turkey poults to shelter from carnivores. But Chamberlain recommends getting down to poult-eye-level to understand what ideal cover should look like.

“It doesn’t matter what part of the species’ range you’re in, [turkeys] have to be able to see,” he explains. “If you want to see the world from a poult’s perspective, lay on your stomach. If you look around you, you need to be able to run very quickly and hide under something. But you have to be able to see in front of you. It needs to be clumpy, patchy, open grasses, shrubs here and there. And a hen needs to be able to stand there and see everywhere around her. Go out to properties that you hunt and look at the world that way, and you will see what I see: There’s not a lot of that.”

If the predators have better visibility than poults and hens, the predators will win, Chamberlain explains. In areas where habitat goes unmanaged for turkey production and survival, understory growth can go from helpful and full of good hiding spots to a nasty maze where young turkeys can’t thrive.

“I’m 51 years old. I can remember as a teenager driving around and hunting forest where there was a lot of disturbance. Now you drive around and everything looks thicker,” Chamberlain says. “Private landowners like timber companies used to use prescribed fire routinely. They don’t often now. If you look at private land ownership patterns in a lot of places in the East, parcels are getting smaller and smaller because [landowners are selling] larger tracts. You may go from a 2,000-acre piece of property that was managed fairly well in the 1990s and it sold in the 2000s and now it’s 10 different tracts and nine of them aren’t managed at all, they just sit there. [That creates] a landscape that is thicker and not as well-managed.”

The Pennsylvania Game Commission has a detailed outline of what prime turkey habitat looks like. According to their turkey management guidance:

Nesting Habitat

Wild turkey hens begin to nest before most of the new growth begins in the spring. Therefore, at least for initial nests, hens need some residual cover from the previous year to conceal their nest from predators. Generally, nesting habitat consists of low, horizontal cover such as low brush, standing raspberry canes from last year or anything that obstructs visibility between ground level and about 3 feet … Mature woodlands with a well-developed understory provide excellent habitat. In wooded areas, turkeys often nest at the base of a tree, fallen log, or boulder, which provide additional concealment from predators. Be sure there are numerous patches of low cover in the vicinity.

Brood Rearing Habitat

Brood habitat generally consists of grasses and forbs, areas with abundant insect life, that the poults need as a food supply for growth. The ground cover should be dense enough to encourage insects, but not so dense as to inhibit the poults’ movement. Brood habitat must be near or adjacent to brushy and wooded areas for escape cover and trees for roosting. Orchards or groves of trees spaced widely enough to allow sunlight penetration and allow room for mowing provide ideal brood habitat when the grassy areas are mowed once or twice a year.

How Hunter Harvest Impacts the Turkey Population Decline

In 2020, the same year that Tennessee hit its low in poult production, hunter harvest hit a record high of 40,000 birds. The following spring, the TWRA instituted some changes in hunting regulations (at the urging of hunters, Shields points out).

“The statewide season bag limit was reduced from four bearded turkeys to three, and ‘bonus’ birds were eliminated. Additionally, in light of steep harvest declines occurring in several counties … the Commission adjusted hunting regulations designed to improve turkey population numbers in these counties,” the report reads. “The spring turkey season in these counties opens two weeks later … and is two weeks shorter, ending with the statewide season closure.”

This delayed start to the hunting season allows time for most breeding to occur without disturbance from hunters and before hunters remove any gobblers, says Shields. In addition to the spring season delay, the state reduced the bag limit for the Tennessee counties along the Mississippi River to two birds.

The changes that nine Tennessee counties saw in 2021 will become effective statewide for the 2023 season. Every turkey hunter in Tennessee will begin the season two weeks later than usual. The bag limit will be two birds and only one jake.

It might seem like Tennessee’s liberal bag limits were irresponsible, given the long decline in poult production. But the harvest limits were rooted in research, and actually follow a trend that state agencies have used to set turkey hunting regulations for decades. But Chamberlain says the old guidelines for setting harvest limits may now be outdated in many states.

“Historical data that was largely used to make recommendations for seasons, bag limits, and timing—that work suggested we needed to kill 30 percent or less of our toms each year if we wanted to ensure quality hunting,” Chamberlain says, noting that 30 percent was based on wild turkey production that’s more than double what we see now. “We were making a lot more birds then. We see harvest from 30 to 40 percent, 50 percent of some populations, and that’s just not sustainable.”

The opinion that turkey harvest needs to be significantly reduced isn’t exactly a popular one among hunters. Shields likens Tennessee turkey hunters to Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities: Hunters in Eastern Tennessee are more vocally opposed to the regulatory changes than Western Tennessee, where turkey populations seem to struggle more with the Mississippi flooding and urban sprawl around Nashville and Memphis.

As a lifelong turkey hunter, Chamberlain understands these frustrations.

“I don’t like hearing that anymore than anyone else does, because I was a turkey hunter long before I was a turkey scientist,” he explains. “At the end of the day, I live for the spring. In my neck of the woods, it’s spring, and turkeys are gobbling, and I want to go. I’m ready to call a turkey up and shoot him. Facing the realization that changes have occurred is hard to accept.

“At a population level, you see pretty significant declines in gobbling activity as hunting pressure gets higher,” Chamberlain says. “Once hunting gets going, gobbling is starting to decline on a daily basis, and may get to very low levels where birds are gobbling not at all or they’re gobbling very little in the tree and they’re not gobbling on the ground at all. In some cases we’re shooting the vocal birds, and in other cases the birds that aren’t shot are changing how they’re behaving … and that’s just a response to risk. They perceive risk and they change their behavior accordingly. They’re wired to reproduce and survive. And if there’s something that causes risk to that survival, they have to react to it. Otherwise, they’re dead.”

Dominance Hierarchy and Later Hunting Seasons

Wild turkeys rely on an intricate social structure that hunters might call a pecking order, but Chamberlain calls “dominance hierarchy.” The most dominant toms and hens are the first to breed, hatch, and raise young. Chamberlain theorizes that when boss toms are killed during the breeding process, it delays the breeding for an entire flock.

“Dominant toms breed more than subordinate toms. They’re more aggressive, more fit, they have longer snoods and more colorful heads, more iridescence. And hens can perceive that,” Chamberlain explains. “What we don’t understand is [what] removing those dominant toms at a particular part of the season [does], if anything … If you went into a population and removed a lot of dominant toms early, then logically, it could matter. We just don’t understand the magnitude of that effect. This is hard because we don’t see who is dominant a lot of the time. We just go out there and interact with a bird or two, but we don’t really know what’s going on.”

According to the National Wild Turkey Federation, breeding doesn’t begin until late February or early March in Eastern turkey populations. It can sometimes last until the early summer and poults begin hatching in June. As of 2020, most states’ turkey hunting seasons began in April. Some waited until May but others began as early as March.

“There’s research back in the 1980s showing that if you want to time a turkey season the most conservatively you can, you open it when most of your breeding is already finished, which is when hens go to nest. At that point they’re not receptive to being bred,” Chamberlain explains. “That’s what the research has shown for decades, but a lot of people have never heard that research.”

Shields explains that the two-week delay in nine Tennessee counties in 2021 acted as a test for reproductive success after giving turkeys extra time to breed. It still might be too early to tell whether the delay made a big difference, but one region that had a later start to the season in 2021 had a fantastic reproductive year in 2022.

“We were trying to stay out of the woods for a little bit and let the birds do their thing before we start interfering with their behavior. We wanted to see if it would actually produce better reproductive success before recommending rolling it out for the whole state,” he says. “Last year Region 1, where we did the delay [in 2021], was the best region in the state in terms of reproduction. But we’ve had a research project going on in the south-central part of the state that included some of the other delayed counties and we haven’t really seen any effects. So yes, our thought was that if we waited a couple weeks for the dominant gobblers to do their thing, that would help. But I think it’s a little bit of a mixed bag.”

What Can States Do About the Turkey Population Decline?

Tennessee’s bag limit and season date changes embody the key thing Chamberlain thinks states can do to help slow the turkey population decline.

“Ultimately it hinges on states taking the initiative and implementing harvest strategies that make sense biologically,” he says. “I don’t envy state agencies at all. They have a tough job. They are mandated with ensuring sustainable populations and they’re also subjected to political pressures and social pressures. In a lot of these states, politics drive decision-making and trump biology. Changes are not popular with many hunters and not popular with politics. In an ideal world, states would have social license. We [would] give them the flexibility, lay off their backs, and let them do what they think is, biologically, the best, and we just live with it. But that’s not reality.”

Chamberlain explains that lots of states in the East have changed their turkey seasons in recent years. But those changes have all been a long time coming, especially considering how long poult numbers have been declining. That downturn has lasted close to 50 years in some states.

“Conversations about those changes have been going on for years, they didn’t just start two years ago. Those conversations have been ongoing because these declines have been ongoing,” he says. “These agencies are changing the one thing they can control at the state level, which…is harvest.”

What Can Hunters Do About Turkey Population Decline?

In the East, most of the turkey habitat is on private land. That means private-land hunters and landowners are key to a wild turkey comeback.

When you get out in the turkey woods this spring, Chamberlain says to pay attention to the quality of the habitat you are hunting. Does the world look like a thick jungle from poult-height? Consider some improvements that would improve visibility for birds looking to escape predation.

“You have to give the birds the ability to see. [Use] any tool that will help you create or maintain open vegetation, knee-high or less,” Chamberlain says. “If it’s up to your waist when you’re walking through it, that’s not turkey habitat. Their number-one survival tool is vision. If they can’t see as well, that helps the predator. So any tool you have that can open up the forest and make it more visible, do it.”

This doesn’t require that you own a huge turkey property. Nor do you need excess time and money to turn it into poult heaven. Even if you’re hunting private land with permission, Stiller recommends having a conversation about habitat management with the landowner.

“The single greatest impact hunters and landowners can have to boost local turkey populations is to provide quality habitat,” Stiller says.

“If you have access to private land, even if you don’t own it, and it doesn’t matter if it’s one acre or 10,000 acres, try to positively affect something that’s occurring on that land that would benefit turkeys,” Chamberlain says. “Being able to see, disturbing the forest, burning, mulching, discing—anything that disturbs the ground and stimulates green vegetation. Think outside the box.”

If landowners are interested in habitat improvement but concerned about the cost, remind them of cost-sharing programs with conservation non-profits and state agencies. Simply Google: “[your state name] habitat cost share program.“

“[Often] landowners don’t realize what resources are out there to help them manage their land. That’s a failure on our part, on us collectively,” Chamberlain says. “These are cost-share programs that can be tapped into to offset or, in some cases, completely cover the cost of doing these improvements on your land. If every person that picked up a gun and chased a turkey made it imperative that for every time they did that, they were going to try to affect one acre of land, think about the impact you’d have. And it doesn’t have to be that costly.”

Hunters can also learn more about turkey biology and habitat by checking out Chamberlain’s website, which is being supported by Mossy Oak. Wildturkeylab.com serves as a central hub for some of the most important and interesting research on wild turkeys. The more we know about gobblers, the more we can do to grow their numbers.

Chamberlain also says that it’s important for hunters to be patient with their state agencies when bag limits and season dates change. Several states know it would be safer to change their season structure but fear the hunter backlash.

Acknowledging that wild turkeys are declining throughout much of their range is the first step toward fixing the problem. Chamberlain also warns against getting too comfortable in areas where turkey populations are thriving.

Read Next: How to Hunt Gobblers That Go Ghost

“There are some areas where turkeys appear to be doing quite well. Much of the Northeast and some areas in the upper Midwest seem to be doing well. But there are those in the scientific community, myself included, who are skeptical that will continue,” Chamberlain says, noting that he’s already heard stories from outfitters and landowners in areas like Wisconsin, who are estimating their turkey populations have declined by 50 percent in the last decade. “We’re probably going to be looking at declines in other states where things appear to be good now. … What you’re seeing, pretty much across the eastern United States, is that things have declined. We pretty much know what the causes are. But what we do about it is a challenge.”

— Alex Robinson contributed reporting to this story.