We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

It was spring of 1989 when my father and I perused the sporting goods section at Wal-Mart where small-town fishermen like us bought tackle. Being a youngster easily influenced by colorful marketing of the day, I latched onto a pack of Berkley Tequila Sunrise PowerWorms, mainly because they were pink, purple, and brand-new to the scene. But it also made sense to me that if worms smelled more like something bass naturally eat, they should work better than those that didn’t. Dad wasn’t thrilled to shell out three bucks for a pack of seven .10-cent worms, but he bought them for me anyway. I’m not saying I out-fished my old man that afternoon, but it was clear that the farm pond bass preferred the PowerWorms over anything else. From then on, we were PowerBait believers.

Thirty years later, I got the chance to tour Berkley’s headquarters for an in-person peek behind the curtain. Naively, I had no idea Spirit Lake, IA, was fishing lure Mecca, or, as I stepped through the front doors of the 300,000-sq. ft. manufacturing plant, that it houses Area 51 of the fishing world. I had no idea about the amount of scientific testing Berkeley was utilizing to design lures.

Deep down I always wondered about Berkley’s claims: “Fish Bite and Won’t Let Go.”

But then again, fishermen have historically been sold on anecdotal evidence and not actual science—mainly, I suspect, because little of it existed. After touring Berkley, I found out that that there were literally thousands of experiments building scientific evidence.

Fishing’s Area 51

There are no cameras allowed in the facility—I bet more people have walked on the moon than know the full recipe of Berkley’s Powerbait—so I’ll describe what I witnessed: Past the reception desk there’s a hallway of front-end offices for admins, marketers, designers, engineers, sales staff, and executives much like any other big business. But twin conference rooms whose four walls are lined with every Berkley fishing product you can currently buy begin to reveal the nature of this iconic American company.

Founded by Berkley Bedell in 1937 when he was a 16-year-old fly tier, “Berk” brought full-scale production lines to the facility to mass manufacture soft baits, lures, lines, rods, and more. Over the years there have been many breakthroughs and cash cows. Trilene monofilament, unveiled in 1959, was a whale, but none were bigger than PowerBait Trout Dough which was invented here in 1987 by a Berkley employee and PhD fish physiologist named Dr. Keith Jones. It was a patented, Play-Doh-like bait infused with a secret scent mixture that fooled trout so thoroughly that they’d hold onto the bait longer than other artificial bait. This allowed anglers more time to feel the fish and set the hook, thereby increasing strike-to-hookup ratios. The concept revolutionized the fishing lure industry forever.

The Science Behind the Bait

PowerBait proved so popular among fishermen that it funded more science-based bait development. Soon thereafter Berkley launched PowerWorm and its market dominance soared. (If you live in the South you might be surprised to know Trout Dough remains the firm’s top seller, churning out 20,000 jars of it each day.) Sure, there were other scents available at the time (Fish Formula comes to mind) but most were spray-on, oil-based concoctions. And as I learned, that’s a problem.

“If it’s not water soluble, fish can’t sense it,” said Mark Sexton, Manager of Fish Science & Product Testing. “Go stick your head in a water tank; you can’t smell anything because humans need air to smell. For fish, scent molecules must mix with water. It’s that simple.”

Sure, it sounds simple, but where’s the proof?

For one, Sexton’s been studying fish professionally at Berkley for 23 years; he has access to 34 years of the company’s collective, notarized research on the PowerBait project alone. And we’re not talking “fish stories” where Brand Ambassador Bubba from Birmingham catches a bass and chalks one in the Purple Worm column. We’re talking about repeatable experimentation on fish that are imported into the controlled environment of a lab, placed in various tanks and studied until they are rotated out, unharmed.

As we walked into the first of several live fish experiment stations, the smell of which pleasantly reminded me of Sea World, Sexton asked me to ready my stopwatch as he dabbled “competitor A’s scent” (I’d tell you if I knew) onto a cotton ball and used forceps to insert it into an aquarium occupied by a largemouth. The bass took the bait but in the blink of an eye it spat it out like day-old dip. I didn’t even have time to start the clock.

“A bass can reject a bait, taste it and spit it out, in .25 seconds,” said Sexton. “You know what a good fisherman’s reaction time is to set the hook?” he asked. “About .25 seconds; a dead heat between fish and fisherman.”

Then he inserted a sample plied with PowerBait, and when the same bass inhaled it, I clicked the stopwatch. After 10 seconds it became apparent that the bass actually ate the bait. Sexton said nothing but smiled a little and moved to the next testing apparatus.

“If someone says I’m full of shit,” he said later, “we can prove our claims with data.”

Turns out, Berkley tests its baits for every sense fish have, including sight, sound (lateral line feel), smell, and taste. They do this in various water conditions, for various types of game fish. When they test baits for crappie, for example, they import crappie. Trout? Sometimes the lab houses up to 7,000 of them at once. They experiment, record data, quantify it, draw conclusions and develop baits based on this knowledge of fish behavior. Then they test the bait and perfect it for at least a year—sometimes 20 in the case of Gulp—before it ever sees a store shelf.

Whereas PowerBait was designed to make the fish hold onto the bait longer, Max Scent was developed to attract the fish to the bait and entice it to bite before encouraging it to hold onto it longer. So rather than using more durable and easier-to-mold PVC-based plastics, engineers spent years developing a porous, water-soluble line of soft baits whose material is completely infused with scent. The idea is that the bait will disperse scent yet remain springy enough for energetic action and durable enough for multiple uses. Although I was not allowed to see how any of the scents—PowerBait, MaxScent, and Gulp—were actually manufactured, I saw how they were tested.

In one side-by-side experiment featuring two identical tanks of water, red dye was added to both the competitor’s scent and MaxScent so scientists can easily observe the scent dispersion of each. Immediately after the MaxScent bait was dunked, a plume of scent began to disperse until the entire tank was a red cloud of scent. This visual experiment was pretty compelling. The MaxScent worm attracts fish even if visibility is low or if the dude holding the rod is more interested in working his beer than his bait.

“It’s almost like you’re at grandma’s house watching TV in the living room when she starts baking cookies in the kitchen,” said Berkley Consumables Category Director Jake Dawson. “Pretty soon you’re in there grabbing one. That’s the concept of Max Scent.”

Next, we stood near the edge of an in-ground fish tank about 20 yards long and 10 yards wide. The center was partitioned so its circular outside formed an aquatic racetrack that was filled with bass. A train track-like system encircled the tank, and a self-powered trolley ran around the track. The trolly held a fishing rod.

Sexton tied Berkley’s new Frittside crankbait to this contraption and moments later it was trolled around the underwater track. A submerged camera recorded every bite the hookless bait received so it could be counted and compared against other bait designs. Thousands of these tests have been conducted on various lure designs.

Even deeper into the lab—past the long casting tank with an underwater observation window–sat a see-through flow tank where young engineers Kyle Peterson and Dan Spengler set their prototype jerk baits in perpetual motion so they could study minute differences in their actions across various retrieval speeds. It’s no fluke that their latest jerk bait creation, a collaboration with professional angler Hank Cherry and called the “Stunna,” shimmies laterally along its axis each time it settles; it took more than a year to get it to dive and suspend just perfectly so it will remain in the strike zone as long as possible. These two guys looked like proud boy scouts in the finals of the PineWood Derby. Both Peterson and Spengler got their start at Berkley not by obtaining skeepskins from some high-dollar university, but rather by being fishermen who independently developed their own lures at young ages, much like the Berk himself. Spengler eventually earned his Masters degree in fish ecology so he could better understand the why behind the notions he had about a luring fish. But both Spengler and Peterson got their start by being passionate about catching fish.

As fun as prototyping and testing lures on captive fish sounds, the best part of the job is field testing.

“Our baits are proven in the lab but validated in the field,” said Spengler.

Berkley encourages engineers to grab some lures and hit Lake Okoboji that’s literally out Headquarters’ back door, or Spirit Lake that’s a couple miles up HW 71. And that’s exactly what we did next.

Proving it on the Water

Armed with enough Max-Scent worms to make Johnny Morris jealous and a few new-for-’21 products like its Gilly swim bait and PowerBait-skirted jigs designed by jig-master Gary Klein, we took to the water and flogged it with … science.

Although it proved a tough day due to constantly fishing behind the contestants of two ongoing tournaments, we still caught fish. But I already knew PowerBait and Max Scent catch fish, so the question is, would we have caught these pressured bass with Zoom lizards, Senkos or any other brand’s plastics? Honestly, I bet we would’ve caught some. But after having actually witnessed the science behind Berkley’s baits, it’s now tougher than ever for me to throw much else. While I’m no longer the gullible kid at Wal-Mart, I’m now a middle-aged man who’s looking for any edge I can get to land a 10-pounder before I drift off to the big lake in the sky.

Speaking of which, here’s an anecdote I’ll leave you with: When my father was fading a couple years back, I took him to the same 5-acre farm pond where he took me more times than I can count. He could hardly cast at all due to his Parkinsons, and I was moments away from returning him to the nursing home. But I said, “One last cast, Dad,” and though his cast barely cleared the weed edge, it did, and the water exploded. On my father’s very last cast of his life, he landed his biggest bass ever, an 8 lb. 14 oz. giant. What was he using? A Tequila Sunrise PowerWorm, I kid you not.

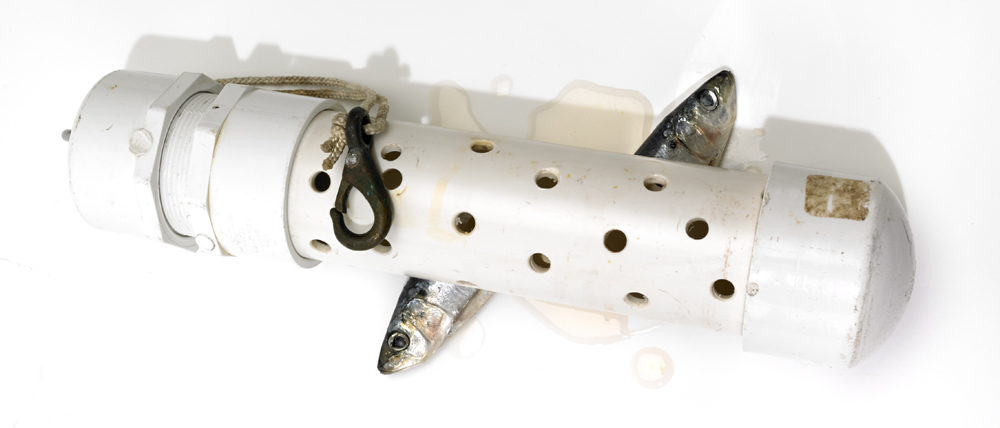

Berkley’s Gilly Soft-Plastic Swimbait

Designed by pro fisherman Mike Ioconelli and inspired by Japan’s ultra-realistic lures, the Gilly is a PowerBait infused soft-plastic swimbait. It’s versatile in that it can be hooked and fished in multiple ways; it’s durable, scented, but what really separates it from the scads of similar baits on the market is it’s incredible action. Engineers spent months perfecting its balance so it swims upright, just like a real bluegill. One look at the bait in the casting tank amazed me. It’s available in three sizes from 90mm to 130mm and a variety of HD colors. I can’t wait to try some on my home lake this summer.