THE BURMESE PYTHON sat still as Bill Booth eased forward. It was coiled and hidden in a tangle of brush and vines, but Booth could see enough to know it was a very big snake. So he crept forward until he could spot the python’s head, just visible through the green leaves. Then he crouched low and reached out with his right hand.

I had tagged along with Booth for four days and nights while he searched wildlife-management areas around the Everglades for a snake like this one. Booth—a 53-year-old firefighter who stands 6 feet 4 inches and is built like a Florida Gators lineman—has been hunting, fishing, and camping in the Glades his whole life. He’s an easygoing Southerner, but his big teddy-bear persona didn’t fool me. Booth is that guy who, on a dare, holds a lit fire-cracker for just a split second longer than any of his friends.

Early on during the trip I had asked him how he goes about actually catching a python once he finds one. His reply: “You grab it behind the head and keep it from wrapping around you.”

That’s one man’s simple solution to a complex ecological problem.

The Python Problem

Burmese pythons have been spreading through South Florida for decades—the first invaders were released by negligent pet owners or sprung from a snake-breeding facility during Hurricane Andrew in 1992. Pythons are efficient predators that adapt perfectly to the warm climate and thick, wet habitat of the Everglades, and they grow large enough that they have no natural predators. Researchers estimate the invasive python population at anywhere from 30,000 to more than 300,000 snakes, and they now range from the -Miami suburbs through the Everglades wilderness. The estimates vary so widely because pythons are difficult to find—every snake sighted indicates 100 more in the wild, according to the United States Geological Survey.

This growing population of apex predators has put a hurt on local mammal populations—pythons have devastated native marsh rabbit numbers—but it has also created a new, weird, exciting, and headline-grabbing hunting opportunity. Python hunting is allowed year-round in 22 state wildlife areas. There is no bag limit on pythons, and they “may be taken by any means other than traps or firearms (unless provided for by specific area regulations),” according to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. The public is not allowed to hunt pythons inside the 1.5-million-acre Everglades National Park.

“Populations of fur-bearing mammals are virtually nonexistent, and studies show that’s because of pythons,” says Randy Smith, spokesperson for the South Florida Water Management District. “Pythons are disrupting the entire ecosystem of the Everglades.”

License to Thrill

Bill Booth is one of the state’s licensed python bounty hunters—both the FWCC and the SFWMD contract hunters to catch and kill pythons. Booth gets paid minimum wage to search for Burmese pythons, and then receives a bounty for every snake he brings in. The bigger the snake, the higher the payday. These guys aren’t getting rich—the state-record python taped 17 feet and brought in $375—but the extra money pays for gas and helps motivate the area’s best snake hunters to bag more pythons. So far, hunters for the SFWMD have caught 870 pythons, which added up to 6,182 feet of serpent.

Besides removing snakes from the landscape, the python hunters are providing another useful service: They’re stirring up publicity. Big snakes make for big news. That state-record snake, caught in December, made national headlines. Booth has hosted a variety of media members and television-show hosts on python hunts. Last year he took out Troy Landry from Swamp People, as well as Ozzy Osbourne, and this year he’s working on a pilot episode for a Discovery Channel show.

More awareness about invasive pythons makes it less likely that pet owners will release their unwanted snakes in the Everglades, unwittingly contributing to an ecological disaster. Booth also hopes that more positive attention on python hunting might help persuade the park service to allow snake hunting in Everglades National Park, which Booth sees as the great Burmese python motherlode.

“They have this nice little breeding ground [in the park], and all the snakes have moved out from there,” Booth says.

The publicity has also sparked a growing interest in snake hunting among regular sportsmen looking for an adrenaline rush, a unique hunting experience, and a python-skin trophy. In the past few months, Booth has started guiding sportsmen looking for the chance to catch a wild python. He’s already taken out 15 hunters, and more are booking every week.

In the Hunt

The old war adage “hours of boredom punctuated by moments of terror” applies perfectly to python hunting. We spent our nights driving levy roads looking for snakes in Booth’s truck’s headlight beams. We poked along at 10 mph through miles and miles of cypress swamp and marsh grass. It was early spring, and the snakes were just starting to get active at night. The hotter, muggier, and buggier it is, the better for catching pythons. Each night, we hoped to spot snakes on gravel roads soaking up heat left over from the day. Then, first thing in the morning, we’d drive those same roads, looking for snakes sunning in the ditches.

During one of our long, slow drives, Booth showed me a photo on his phone of a kid in his 20s from New Jersey who had come down to participate in the Python Challenge—a tournament that Florida used to promote. The kid had blood running from his head and arms, and a big grin on his face. Booth said the kid caught a python while his dad was filming him, but the snake bit him multiple times and was about to overtake the kid until his dad jumped in and helped wrestle the snake off his son.

“If a big snake gets ahold of you and you are by yourself, you’re not going to be able to overpower it,” Booth says. “They’re all muscle and they’re very, very powerful. They can kill you.”

After three nighttime and morning patrols, we had yet to spot a single python. Big pythons don’t move much and don’t have to feed very often. And the cover was so thick, we could have passed snakes without ever knowing it.

“You cover hundreds of miles over a week, and you come up with one or two snakes,” Booth says. “It’s a lot harder to find them than you think it is.”

We did spot water moccasins and black snakes and hundreds of alligators. Just as interesting is what we didn’t see: not a single small mammal during our whole trip.

So on the last day, Booth decided we should try taking his boat down one of the nearby

canals. As the sun rose over the cypress trees, we slowly motored down the canal, searching the banks for a glimpse of python scales.

By lunchtime we had made it a few miles without finding a python, so we got out on one of the small islands along the canal to tromp around. The island was about 60 yards wide by 200 yards long, and was completely overgrown with papaya trees and gumbo-limbo.

“Watch yourself,” Booth said as we worked around the island. “You don’t want to step on a water moccasin out here.”

We pushed through the scrub and briars in a loop, and were headed back toward the boat when Booth pointed and grabbed me by the arm.

“Look at that! It’s a Burmese.”

And sure enough, a 2-foot section of snake was visible in the vegetation about 10 feet ahead of us. Then all hell broke loose.

Booth grabbed the snake just behind the head and jumped on its body, trying to flatten it out with his legs. The snake instinctively coiled around Booth’s forearms and tried to turn to bite its attacker. Because this was an exceptionally large python, Booth instructed me to grab the snake’s tail and pull it away from him to keep it from wrapping around his torso or neck.

I found the writhing tail and yanked it back to stretch out the snake. I was shocked at how incredibly long it was. The very tip of the snake’s tail was bone hard, and it wrapped around my hand and pressed into my wrist as I pulled. It smelled putrid—somewhere between a rutting bull elk and a rotting fish. Even though I was clear from any real danger, I couldn’t help but wonder what I should do if the python sunk its teeth into Booth. The .22 rifle, which Booth had brought along in case of an emergency, was back in the boat.

Booth wrestled with the snake and eventually pulled it loose from the tangle of vegetation. Cold-blooded critters don’t have the endurance that warm-blooded mammals do, and Booth was able to hold on to the snake just long enough to play it out. When the python finally tired, we stuffed it into a laundry bag and hauled it back to the boat. Eventually, Booth shot the snake with his rifle while it was coiled in the bag. Back at camp, we measured it at just under 15 feet long, and Booth guessed its weight to be about 120 pounds.

“It’s too bad we have to kill them,” Booth tells me as he skins out the python. “But these snakes just don’t belong here.”

The Super Predator

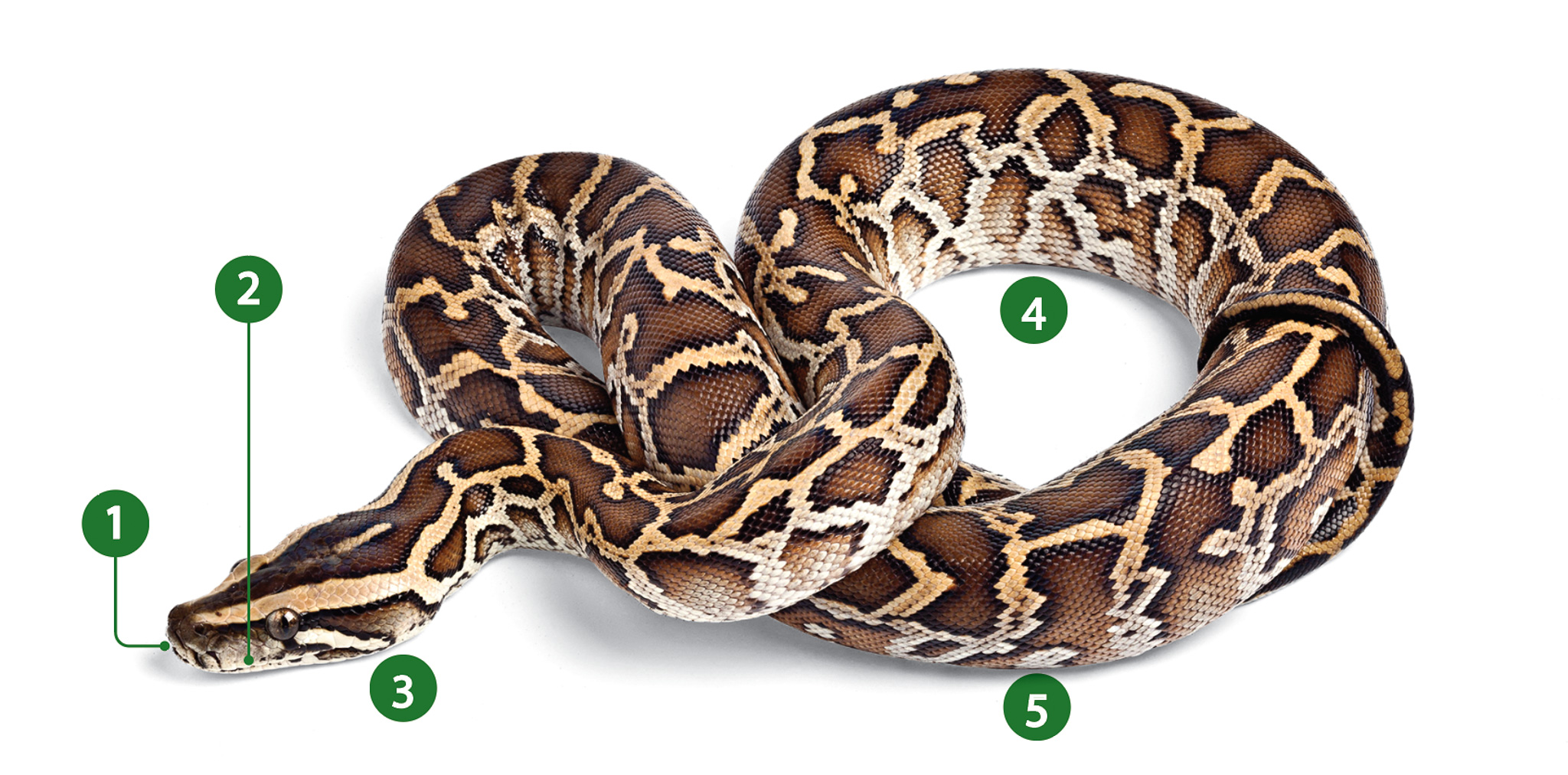

Burmese pythons are docile by nature (there is no record of an unprovoked wild python ever attacking a person in Florida), but these characteristics make them the top predator in

the Glades.

- Tongue: Chemical receptors help with stalking prey.

- Teeth: Six rows of needlelike teeth curve back toward the snake’s gullet and are designed to catch and hold struggling prey.

- Jaws: A flexible system of muscles and tendons allows the snake to swallow large critters whole.

- Body: Powerful coils constrict and cut off blood circulation to the prey’s brain, killing victims surprisingly fast.

- Digestive system: Stomach enzymes and acids break down prey quickly. After a large meal, a python can go for months without feeding again. Pythons commonly eat small mammals, but researchers have found them with alligators and full-grown deer in their stomachs. After swallowing a supersize meal, a python can increase the size of its heart, intestines, liver, kidneys, and pancreas to help with digestion.

This story originally ran in the Spring 2018 issue. Read more OL+ stories.