Bass will take just about anything that suggests food to them, but it has to have a natural look, smell or move.If an angler can satisfy any of those requirements when a bass is hungry, he might get a strike.

But that principle only goes so far. To some degree, bass are conditioned by instinct to expect their food to conform to certain natural laws. A frog, for instance, is not supposed to be bobbing in the waves of a New England lake a half-mile from shore in November. Such anomalies, duplicated by lures put in the wrong place at the wrong time, probably repel bass more than they attract them. On the flip side, an angler can increase the number of strikes he gets by observing the rules of engagement as they apply to seasonal determinants. Consider bass and bugs.

A Taste for Insects

In summer, bass prey primarily on minnows, frogs, crayfish and juvenile fish. Sure, they’ll eat the occasional terrestrial insect encountered along the shorelineÐa clumsy caterpillar here, a wayward June bug thereÐbut it’s more a snack than the main meal. When the days begin to shorten, however, and a chill creeps into the mornings and evenings of Indian summer, bugs play a larger role in the diets of bass. Perhaps the mental picture of a fat bluegill or shad is replaced by the image of a plump cricket, but whatever the reason, something in the genetic memory of bass tells them it’s time to start prowling the banks for the stray insects that just sort of let go of their summer perches and drop into the water.

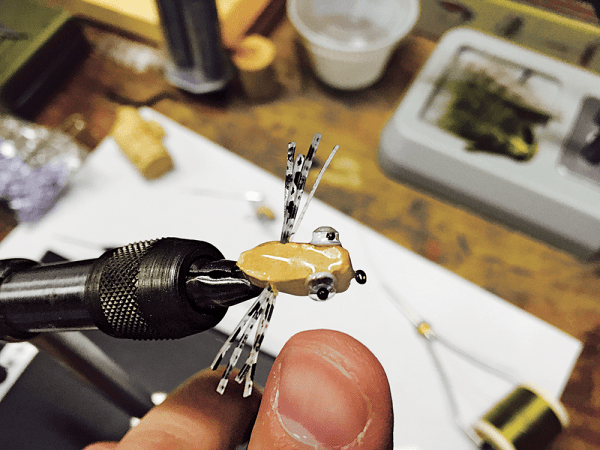

Flyfishing tackle and big poppers or imitators such as Dave’s Hopper are old favorites to catch bass with a taste for terrestrials. Plug fishermen can choose from a number of topwater lures that suggest that they are bugs by their finish or duplicate the real thing.

Lures that mimic bugs are nothing new. The first one patented was called The Flying Hellgrammite, an oxymoron if ever there was one. Introduced in 1883 by Harry Comstock, the sinking lure was a wooden imitation of a hellgrammite, the submergent larval form of the dobsonfly.

In 1939, lure maker Fred Arbogast carved a cicada or summer locust out of a piece of broomstick, screwed a curved metal bill to its nose and called it a Jitterbug. The floater sold well. The following year, rival lure manufacturer James Heddon’s Sons started to market a topwater plug that Jim Donaly had invented in 1906. Donaly named it the WOW. When Heddon’s Sons obtained rights to the lure, the company changed the name to the Crazy Crawler. Like the Jitterbug and another Arbogast introduction, the Hula Popper, the Crazy Crawler still is being marketed and catching plenty of bass.

The Jitterbug, Hula Popper and Crazy Crawler are suggestive topwater lures. They’re not shaped like anything in particular, but to a bass, any one of them could be a frog, insect, field mouse, baby bird or even a baitfish, depending on the color pattern the lure wears and how the plug is retrieved. A newer generation of insect imitators such as the Rebel Crickhopper, Cat-R-Crawler and Bumblebug is less subtle in appearance and represents hard-plastic clones of living insects.

Lures that imitate bugs range from 1/10-ounce (in the case of the Rebel family of baits) to 3/8-ounce or so (for bigger plugs like the Hula Popper).

Be the Bug

Contrary to the angling adage “big baits catch big fish,” downsizing insect baits may draw more strikes from bass of all sizes than bigger versions.

“I use smaller lures like the Crickhopper and the 1/8-ounce Tiny Torpedo i n the early fall, and the bass I catch then are about the same size as the ones I catch in the summer on much bulkier baits,” observes Bill Schultz, a bass fisherman who lives near Milwaukee. “I caught a 51/2-pound largemouth in a Green Bay feeder creek last year and a 31/2-pound smallmouth in Sturgeon Bay. Those are pretty good fish for up heere and they both took 1/8-ounce lures that were about an inch long. Maybe the fish are just programmed to look for food in smaller bites in the fall.”

A medium-action spinning rod and reel loaded with 4- or 6-pound-test monofilament matches up well with the ultralight baits. Schultz employs an ultralight Shimano spinning reel teamed with a six-foot, six-inch light-action spinning rod marketed by St. Croix. Often, Schultz fishes from the bank so the longer rod helps him cast the light baits greater distances.

Bug baits can be especially effective when fished along banks overgrown with shrubs and trees, since that’s where bass expect to find insects. Considering the diminutive size of such lures and the small amount of movement required to present them properly, these topwaters are ideal choices for quiet farm ponds and slow-moving streams. However, the lures still can fool bass in swifter rivers, as long as they’re kept in slack water.

Insect lures should be retrieved in a manner that corresponds with the behavior of their natural counterparts. When a horsefly hits the water it might lie there immobile for a few seconds and then begin its feeble attempts to move away. A grasshopper might begin a series of erratic scudding movements across the surface, separated by short pauses. It’s not necessary to move the plug more than a few feet before cranking it in and trying again. Be prepared for a hit the moment you start reeling in the lure. Sometimes no retrieve is best; simply letting the lure stay where it lands for a minute or so might result in a jarring strike. Some purists might scoff at the notion of using a plastic plug that looks like the mother of all insects, but that’s their call. Bug baits are especially effective this time of year and in the end fishing is all about giving bass what they want, not what you want to give them.