Imagine a lake where there’s very little fishing pressure and the bass grow big and largely unmolested. An angler doesn’t need specialized gear or even a boat on this lake, and he can fish it thoroughly within an hour or two.

Actually, it doesn’t take much imagination to conjure up such a scenario. It already exists throughout America in the form of farm ponds and privately owned reservoirs of various sizes.

Farm ponds across the nation have spawned several generations of bass enthusiasts who gained their early fishing education walking the shorelines of these small lakes. Such bodies of water have always been ideal places to introduce youngsters to fishing. But farm ponds are not just child’s playwe are talking serious bass action here.

“There are jillions of farm ponds in every corner of the country that provide good fishing,” says Bill Dance, longtime host of TNN’s Bill Dance Outdoors and the designer of several bass ponds in his native Tennessee. “As a youngster, I got my first taste of bass fishing in a pond, and I still enjoy fishing farm ponds whenever I can.”

“There’s a lot to like about fishing farm ponds,” adds Kenyon Hill, a professional bass fisherman who grew up fishing numerous state soil conservation lakes in Oklahoma. “The best thing about it is that, by their very nature, farm ponds eliminate the hardest part of fishing in general: locating the bass. The fish are right there, not somewhere two miles or so down the lake, which is usually the case when you’re fishing a big reservoir.

“And farm ponds are notorious for giving up big bass. As a rule they don’t get much fishing pressure, so the fish grow big and aggressive.”

Such lakes are particularly productive in the spring and fall, but many remain prolific throughout the year. Even ponds in southern latitudes that contain clear water can be good winter fisheries for anglers who use small lures and light line.

As a rule of thumb, the bigger the farm pond, the more productive it is likely to be, because it typically contains a greater variety of bass habitats. Most ponds are fished on foot, but the larger lakes are better exploited by a johnboat equipped with a bow-mounted electric trolling motor.

It is important to approach a farm pond as you would a large lake, regardless of whether you are hoofing it along the shoreline, puttering around in a small boat, wading or tubing. Farm-pond bass are no different than bass in a huge lake. With that in mind, farm-pond veterans look at ponds as miniature reservoirs and target similar spots that normally hold bass in big waters. That is generally a simple matter, since the layout of the bass’s environment is usually visible from the shoreline. What you can’t see, you probably can judge fairly accurately.

“The first step when fishing a pond is to learn the configuration of the pond and locate the structure and cover,” Dance advises. “Check out the shoreline for visible cover like lily pads or brush that might hold fish. If you’re fishing from a boat and have a depth finder, graph the bottom to look for bottom-contour features, especially any shoreline structure that extends out into the pond. If you’re just going to be walking the bank of a pond you’ve got permission to fish, ask the owner for information such as where a ditch, channel, depression or point might be located in the pond.”

Structure and cover hot spots in a farm pond might include: * A point that extends out into the lake (giving resident bass the option of both shallow and deeper water nearby).

A shallow pocket where bass can dart in and trap baitfish.

Any small creek, branch or ditch that enters the pond.

A culvert that delivers water or creates current.

Any type of wooden cover-stump, log, treetop or boat dock.

Shoreline vegetation.

Trees that cast eir shadows on the water.

Establishing the prevailing depth of the bass is a key to scoring consistently in farm ponds. Although Dance often catches fish off mid-depth structure and deeper spots, Texas biologist and farm-pond expert Bob Lusk believes that most farm-pond largemouths live in shallow water (eight feet or less) throughout the year.

Once potential bass hangouts have been pinpointed, it is critical to take the proper approach, especially when fishing afoot.

“When you walk the bank, it’s very important to be as quiet as possible and fish each area thoroughly,” Dance suggests. “As you move from one spot to another, it’s best to circle out 30 to 40 feet away from the shoreline if you can. By circling out, it’s less likely you’ll spook fish along or close to the bank.”

Hill emphasizes simplicity, particularly in regard to lure selection. Imagine a lake where there’s very little fishing pressure and the bass grow big and largely unmolested.

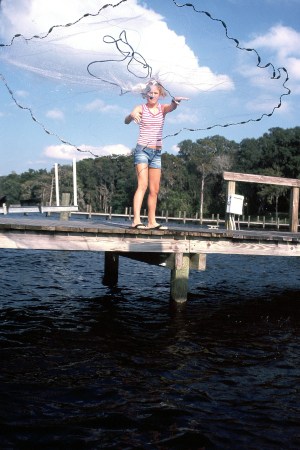

|| |—| | Survey a farm pond’s cover and structure; then develop fishing strategies accordingly. Photo: Bill Buckley | An angler doesn’t need specialized gear or even a boat on this lake, and he can fish it thoroughly within an hour or two.

Actually, it doesn’t take much imagination to conjure up such a scenario. It already exists throughout America in the form of farm ponds and privately owned reservoirs of various sizes.

Farm ponds across the nation have spawned several generations of bass enthusiasts who gained their early fishing education walking the shorelines of these small lakes. Such bodies of water have always been ideal places to introduce youngsters to fishing. But farm ponds are not just child’s playwe are talking serious bass action here.

“There are jillions of farm ponds in every corner of the country that provide good fishing,” says Bill Dance, longtime host of TNN’s Bill Dance Outdoors and the designer of several bass ponds in his native Tennessee. “As a youngster, I got my first taste of bass fishing in a pond, and I still enjoy fishing farm ponds whenever I can.”

“There’s a lot to like about fishing farm ponds,” adds Kenyon Hill, a professional bass fisherman who grew up fishing numerous state soil conservation lakes in Oklahoma. “The best thing about it is that, by their very nature, farm ponds eliminate the hardest part of fishing in general: locating the bass. The fish are right there, not somewhere two miles or so down the lake, which is usually the case when you’re fishing a big reservoir.

“And farm ponds are notorious for giving up big bass. As a rule they don’t get much fishing pressure, so the fish grow big and aggressive.”

Such lakes are particularly productive in the spring and fall, but many remain prolific throughout the year. Even ponds in southern latitudes that contain clear water can be good winter fisheries for anglers who use small lures and light line.

As a rule of thumb, the bigger the farm pond, the more productive it is likely to be, because it typically contains a greater variety of bass habitats. Most ponds are fished on foot, but the larger lakes are better exploited by a johnboat equipped with a bow-mounted electric trolling motor.

It is important to approach a farm pond as you would a large lake, regardless of whether you are hoofing it along the shoreline, puttering around in a small boat, wading or tubing. Farm-pond bass are no different than bass in a huge lake. With that in mind, farm-pond veterans look at ponds as miniature reservoirs and target similar spots that normally hold bass in big waters. That is generally a simple matter, since the layout of the bass’s environment is usually visible from the shoreline. What you can’t see, you probably can judge fairly accurately.

“The first step when fishing a pond is to learn the configuration of the pond and locate the structure and cover,” Dance advises. “Check out the shoreline for visible cover like lily pads or brush that might hold fish. If you’re fishing from a boat and have a depth finder, graph the bottom to look for bottom-contour features, especially any shoreline structure that extends out into the pond. If you’re just going to be walking the bank of a pond you’ve got permission to fish, ask the owner for information such as where a ditch, channel, depression or point might be located in the pond.”

Structure and cover hot spots in a farm pond might include: * A point that extends out into the lake (giving resident bass the option of both shallow and deeper water nearby).

A shallow pocket where bass can dart in and trap baitfish.

Any small creek, branch or ditch that enters the pond.

A culvert that delivers water or creates current.

Any type of wooden cover-stump, log, treetop or boat dock.

Shoreline vegetation.

Trees that cast their shadows on the water.

Establishing the prevailing depth of the bass is a key to scoring consistently in farm ponds. Although Dance often catches fish off mid-depth structure and deeper spots, Texas biologist and farm-pond expert Bob Lusk believes that most farm-pond largemouths live in shallow water (eight feet or less) throughout the year.

Once potential bass hangouts have been pinpointed, it is critical to take the proper approach, especially when fishing afoot.

“When you walk the bank, it’s very important to be as quiet as possible and fish each area thoroughly,” Dance suggests. “As you move from one spot to another, it’s best to circle out 30 to 40 feet away from the shoreline if you can. By circling out, it’s less likely you’ll spook fish along or close to the bank.”

Hill emphasizes simplicity, particularly in regard to lure selection. Although he has his favorite baits, he recommends “matching the hatch,” which involves selecting lures that resemble the size and color of the dominant bass forage in the pond (probably shore minnows or bluegills).

Florida farm-pond addict Sam Aversa is a proponent of utilizing big baits in lakes where he knows big bass live. Among his favorite lures are a Heddon Zara Spook topwater lure and a Texas-rigged, 10-inch plastic worm. Regardless of the bait he selects, Dance uses a series of fan-casts when he’s pond fishingeither from the bank or a boat.

“Start with a cast as close to the target as you can,”advises Dance. “Then, on your next cast, place your lure out just a shade farther. If your first cast was at the 9 o’clock position, for example, make your next cm the shoreline. What you can’t see, you probably can judge fairly accurately.

“The first step when fishing a pond is to learn the configuration of the pond and locate the structure and cover,” Dance advises. “Check out the shoreline for visible cover like lily pads or brush that might hold fish. If you’re fishing from a boat and have a depth finder, graph the bottom to look for bottom-contour features, especially any shoreline structure that extends out into the pond. If you’re just going to be walking the bank of a pond you’ve got permission to fish, ask the owner for information such as where a ditch, channel, depression or point might be located in the pond.”

Structure and cover hot spots in a farm pond might include: * A point that extends out into the lake (giving resident bass the option of both shallow and deeper water nearby).

A shallow pocket where bass can dart in and trap baitfish.

Any small creek, branch or ditch that enters the pond.

A culvert that delivers water or creates current.

Any type of wooden cover-stump, log, treetop or boat dock.

Shoreline vegetation.

Trees that cast their shadows on the water.

Establishing the prevailing depth of the bass is a key to scoring consistently in farm ponds. Although Dance often catches fish off mid-depth structure and deeper spots, Texas biologist and farm-pond expert Bob Lusk believes that most farm-pond largemouths live in shallow water (eight feet or less) throughout the year.

Once potential bass hangouts have been pinpointed, it is critical to take the proper approach, especially when fishing afoot.

“When you walk the bank, it’s very important to be as quiet as possible and fish each area thoroughly,” Dance suggests. “As you move from one spot to another, it’s best to circle out 30 to 40 feet away from the shoreline if you can. By circling out, it’s less likely you’ll spook fish along or close to the bank.”

Hill emphasizes simplicity, particularly in regard to lure selection. Although he has his favorite baits, he recommends “matching the hatch,” which involves selecting lures that resemble the size and color of the dominant bass forage in the pond (probably shore minnows or bluegills).

Florida farm-pond addict Sam Aversa is a proponent of utilizing big baits in lakes where he knows big bass live. Among his favorite lures are a Heddon Zara Spook topwater lure and a Texas-rigged, 10-inch plastic worm. Regardless of the bait he selects, Dance uses a series of fan-casts when he’s pond fishingeither from the bank or a boat.

“Start with a cast as close to the target as you can,”advises Dance. “Then, on your next cast, place your lure out just a shade farther. If your first cast was at the 9 o’clock position, for example, make your next c