At some point ona special day, a fight with a fish becomes more than just an effort to get itin the boat. Whether it’s because of the fish’s size or its determination, theact of subduing it transcends mere physical labor. The battle becomes a test ofman’s will to overcome whatever obstacles nature sets before him.

Santiago in Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea knew that a fight with a big fish helpsdefine a person. These fishermen know it, too. Here’s how they learned.

Taking a Dive for a Marlin

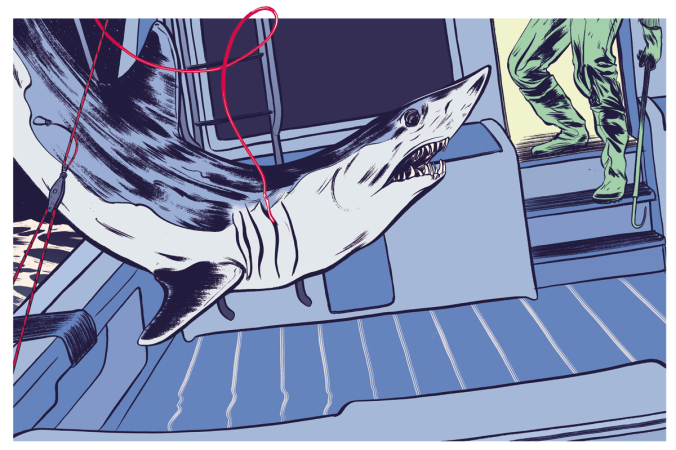

IT WAS GUY HARVEY’S IDEA. After almost four hours of tug-of-war with a world-record-classblack marlin last January off the west coast of Panama, angler Neil Patrickdecided it was time to subdue the fish, tag it and let it go. Either he or the1,200-pound fish had to have relief, and the marlin seemed ready to fight toits death.

Harvey, a noted Florida artist who specializes in saltwater fish portraits and is host of thetelevision series Portraits From the Deep, offered a solution. Although Patrickhad not been able to coax the marlin close enough to tag it, the 15-foot leader was practically within reach. As Harvey saw it, all he had to do was put on hisscuba gear, dive into the water, hook the line from another fighting rig to theswivel of the leader and give Patrick some help by double-teaming the marlinwith two rods. The plan would eliminate world-record consideration, but it wasin the best interest of the giant marlin if it was to survive.

Despite improbable odds, Harvey’s plan was set in motion. He was aboard another boat,where he and his fishing buddy Bill Shedd made ready to join the fray. Patrickwas battling the marlin with a 50-pound-class outfit, which was a bit like taking a knife to a gunfight. At least Shedd was equipped with a stouter 80-pound-class setup. The skipper of the boat on which Harvey and Shedd werefishing eased closer to Patrick’s boat. Shedd and a mate leaped into its cockpit.

Harvey went under the boat for a look. Swimming back topside, he in structed a boat mate to handhim the running line of Shedd’s rig. He then followed Patrick’s line down some40 feet deep, where he would attempt to attach the snap swivel of Shedd’s lineto the swivel that connected Patrick’s line with his leader. All the while,Harvey had to keep a wary eye on the enraged marlin and swim fast enough to keep up with the boats. It took seven attempts, but he finally accomplished hismission.

Thirty minutes later Shedd and Patrick had the marlin boatside. A mate attached a tracking taghigh on its back before another mate cut the leader.

Shedd, president of the American Fishing Tackle Company (AFTCO), can’t say what impressed him more, the size of the fish or Harvey’s intervention.

“There’s no doubt in our minds that the marlin would have been a record, and it put up an awesome fight,” says Shedd, of Irvine, Calif. “But Guy doing what hedid to help ensure that the fish could be tagged and released was really something special. It’s hard enough to attach a leader to a line in a moving boat without having a fish on, but doing it underwater in the middle of a fight like that is just phenomenal.”

Incidentally, the50-pound-class world record for black marlin is 1,124 pounds. Patrick, an Australian who has caught other “granders,” figured the black he foughtweighed more than 1,200 pounds. Everyone else who was there agrees. And that’snot just a fish story. Harvey, Patrick and Shedd are among the 21 members who compose the board of trustees of the International Game Fish Association(IGFA), the registrar of world records for freshwater and saltwater fish.

The Log That Moved

TIM PRUITT, HIS WIFE, Carla, and their friend Tony Pfeiffer had been fishing the Mississippi River since 6 o’clock on the evening of May 21, 2005. By 11:30 they hadn’t had so much as a nibble. Lightning was beginning to flash, and the rumble of distant thunder grew louder. It was time to go, Pruitt decided; the catfish weren’t biting anyway.

Just as the Illinois angler was about to reel in the last line, baited with the forward section of a foot-long skipjack herring, the rod tip suddenly began to arch under the weight of a steady pull. “I grabbed the rod and felt for afish,” says Pruitt, who lives in Alton. “My first thought was that Ihad snagged a log. The current was really rolling. But then the logmoved.”

Pruitt instantly realized two things when he set the Gamakatsu 10/0 Octopus hook: The log wasindeed a fish, and it was huge.

“I must havehit a nerve in the catfish’s mouth when I set the hook because it ripped off a hundred yards of line before we could get the anchor up, crank the motor and goafter it,” remembers Pruitt. “All I could do was hang on. When itdecided to go, it went.” Pruitt, whose bait-casting outfit was loaded with40-pound-test line, fought the fish for almost 45 minutes, until a quarter past midnight. When he and Pfeiffer tried to net it, the catfish was so heavy itbroke the handle.

The anglers then manhandled the fish into the boat as best they could and headed for the nearest set of certified scales. The blue catfish weighed 124 pounds, or 2 1/2 poundsmore than the previous world record, caught in Lake Texoma, Texas, in early2004. The IGFA has since certified Pruitt’s fish as the new world record.

Pruitt wasn’texactly surprised that he caught such a fish, because that’s all he goes after.His previous heaviest blue weighed 95 pounds.

“You cancatch catfish any time of day, but I’m not just interested in catching catfish;I’m interested in catching the biggest,” says Pruitt. “That’s why Ialmost always fish at night, especially in the summer. That’s when the biggestblues like to come out and play.”

Just as Pruitt’sfather and grandfather taught him how to fish, Pruitt is teaching his12-year-old son Brian how to lure big whiskerheads. This fall, Brian hauled ina 55-pound blue catfish while night-fishing with his dad.

The Fight of His Life

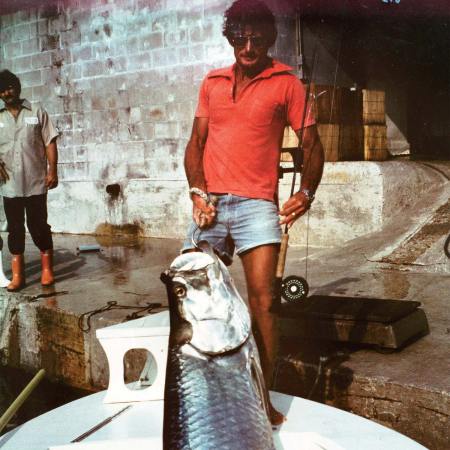

FLYFISHING LEGENDBILLY Pate has set several saltwater records, including the previousworld-record tarpon of 188 pounds. He was the first flyfisherman to catch ablue marlin, too. But the fish he remembers best, and the one that is stilltalked about around the docks at Homosassa, Fla., was a tarpon that didn’t setany records.

Pate, ofIslamorada, Fla., encountered the fish that gained him more fame than any otheron a spring morning in May 1991. Pate usually fished the flats near the mouthof the Homosassa River on Florida’s west coast with a guide or a friend. Thisday, the guide couldn’t go, so Pate fished by himself.

After making theshort run to the fishing grounds, Pate saw that guides and their clients werefighting tarpon just outside the river’s mouth. He gave them a wide berth andcame in south of the armada of fishing boats. Killing his engine, Pate watchedthe action from a distance and noticed that the other boats were gettingcloser. He could tell by the way the flyfishermen were casting that tarpon weremoving toward him. No sooner had he climbed into the forward casting platformof his boat than Pate saw the shadows of a dozen or more tarpon sliding throughthe shallows within casting distance.

“I alwayslike to cast to the biggest tarpon in the bunch, and in this case it was thelead fish,” recalls Pate, who dropped a 5-inch tarpon streamer in front ofthe school. Immediately, the foremost tarpon swirled on the fly and inhaled it.Pate reared back on his heavy rod and the fish went airborne. Though it wasn’tlong, the tarpon looked bigger around than a beer barrel. As it fell back tothe water, Pate began to wonder if he had bitten off more than he couldchew.

Guides andanglers in the nearby boats quickly saw that Pate was tethered to a tarpon thathe couldn’t hope to beat by himself. In fact, Pate had no intention of boatingthe fish until he saw it leap for the first time.

“I thought itmight be a record. It looked every bit as big as my world record at the time[188 pounds],” recalls Pate. “So I decided, “What the heck, I’lljust see how it goes and if I can get it in the boat somehow, I will.'”

Pate, whocontrols his flats boat with two electric trolling motors mounted on eitherside, managed to keep up with the tarpon as it towed him to sea. Luckily, thefish turned and headed back toward shore. The other boats gave Pate a wideberth, and the tarpon eventually played itself out with a series of prodigiousleaps and runs. Three hours into the fight, Pate had the fish on its side. Hisrod was bowed like an arch, but the angler managed to hold onto the tarponwhile he retrieved a lip gaff from under the front deck.

Pate wasconvinced he had a new world record and that he needed to weigh the tarpon oncertified scales. To do that, of course, he had to boat it. “I thought,”How in the world am I going to get this tarpon in over the side by myself?It would be tough enough with two men,'” says Pate. “I looked over myshoulder and saw that one of the guides was coming toward me as fast as hecould go, but he was still a ways off. Without waiting, I put both my hands onthe gaff handle, planted my foot against the gunwale and pulled. About the sametime, the tarpon got its second wind and rushed forward—right into theboat.”

Pate figures thathe’s fought more than 5,000 tarpon during his fishing career. He estimates that”ninety-nine point nine percent of them swam away to fight again.” Notthis one; he had to dispatch the tarpon with a billy club. By then, the helpfulguide had arrived.

“We measuredthe tarpon’s girth and it was forty-four inches. My world record wasforty-three inches around, so that was good,” says Pate. “But it wasseveral inches shorter than my record, and I knew that was going tohurt.”

Back at the dock,the tarpon was hoisted on the scales. It weighed 173 pounds—no record, butstill quite a catch for a solo angler.

“I’ve neverbeen prouder of any fish than I was of that tarpon,” says Pate. “Whenit was over with, after we’d weighed it and everybody had drifted off and I washeaded home in my boat, I thought to myself, “Now, that was reallysomething.'”

Too Tough to Quit

LOUIE SPRAY WAS Astubborn man, even by Wisconsin standards, and he might never had had hisrun-in with “Chin Whiskered Charlie” had it not been for CalJohnson.

Spray was anative son of Hayward, Wis., before it earned the well-deserved designation asthe Muskie Capital of the World. In fact, it was Spray who put Hayward on themap.

By the mid-’40s,when Johnson moved to northern Wisconsin, Spray was the acknowledged muskieking, having already boated two world-record fish. One of them, 59 pounds 8ounces, was caught in 1939; the other, 61 pounds 13 ounces, came in 1940. Bothfish were taken from the famed Chippewa Flowage, formed when the Chippewa Riverwas dammed in 1923.

When Johnson cameto town, he was one of the most famous and revered outdoor writers in thecountry. Declining health and his doctor’s admonitions had forced him tojettison much of his workload, and he chose Hayward as the place where he wouldlive out the remainder of his life doing what he loved best: fishing.

Spray was cutfrom rougher cloth. A lumberjack in his early years and a bootlegger duringProhibition, Spray had become a respectable barkeep by the time Johnson arrivedon the scene.

Spray and Johnsonshared a mutual respect for the other’s fishing talents. When Johnson moved toWisconsin, Spray was 49 years old and seldom fished anymore. But then Johnsoncaught a new world-record muskie of 67 pounds 8 ounces from Lac Courte Oreilleson July 24, 1949, and Spray decided it was time to come out of retirement. Heset out to catch a bigger muskie, and on October 20 of that same year, he foundwhat he was looking for.

Spray knew aboutChin Whiskered Charlie because he had seen the fish on a number of occasions,cruising the clear waters offshore what is now the Indian Trail Resort andsearching for careless perch or crappies. A muskie that was cunning enough toreach 69 pounds 11 ounces and 63½ inches long wouldn’t just fall for anything,but Spray had developed a deadly system that appealed to bigger muskies. Heslow-trolled a big wooden lure as well as a live sucker that was rigged in whatwas called a “quick-set rig,” bristling with hooks. Occasionally Spraywould let the sucker free-swim under a float, then relocate to a new spot andtroll awhile between stops.

Spray startedfishing on October 1 and he didn’t catch anything. He went back the next day,and the next, and several more, with the same results. He slow-trolled ordrifted in straight lines and in big circles; he pulled the baits at varyinglengths from the boat and at different speeds; he stopped and fished in oneplace for a while, then moved to another location. After 19 consecutive days ofthis routine, Spray and the giant muskie finally tangled.

On the afternoonof the 20th day, as Spray was working the sucker toward him with a side-to-sideretrieve, Chin Whiskered Charlie announced his arrival with an enormous swirland took the bait. Spray, who had fishing buddies George Quentmeyer and TedHagg in the boat with him, fought the muskie for more than 30 minutes before itplayed out. Then Spray did something that would eventually keep his name out ofthe IGFA records book: he shot Chin Whiskered Charlie with a .22 caliberhandgun. He kept the firearm with him to subdue muskies. It was a commonpractice in those days.

Having reclaimedthe muskie king crown, Spray enjoyed the title until 1957, when Art Lawton ofAlbany, N.Y., stunned the fishing world with a 69-pound 15-ounce muskie caughtin the St. Lawrence River. Years later, record keepers who examined numerousphotos of the fish became convinced that Lawton’s muskie was too short andlacked the girth to have weighed almost 70 pounds. Spray’s fish was reinstatedas the record, although he didn’t see it happen. Lawton’s record was tossed outin 1992, eight years after Spray’s death.

It was just aswell, perhaps, because Spray didn’t live long enough to see Johnson’s muskiesupplant his in the IGFA record book, either. The IGFA has a stringent set ofrules that govern the methods used to make record catches, and shooting fish topacify them isn’t allowed. Johnson, who died in 1953, used a gaff and not a gunto subdue his muskie and get it in the boat, which was perfectly acceptable tothe IGFA.

Ironically, theWorld Record Muskie Alliance has petitioned the Fresh Water Hall of Fame todismiss Spray’s record on the same grounds used to disqualify Lawton’s fish.Based on an analysis of photos of Spray’s muskie, the group claims that heerred in recording the size of the catch. At press time, the petition was stillunder consideration.

INCREDIBLE CATCHES!

FIVE-SPECIES SLAM Most big-game anglers feel fortunate if they can catch more than two or threespecies of billfish in their lives, but don’t include Hank Manley in theirnumber. In 1997, while fishing off Venezuela aboard his boat, Tribute, Manleybrought to gaff a swordfish, spearfish, blue marlin, white marlin andsailfish—all in one 24-hour period.

ONE TOUGH Swordfish In 1993, while fishing from their 25-foot boat, My Turn II, off SouthernCalifornia, Karl Kogler and Steve Crilly had to take turns fighting what musthave been the most stubborn swordfish ever hooked. The broadbill took a bait at2 p.m. and fought for 23 hours 45 minutes before Kogler and Crilly had itwhipped. The swordfish, which was hooked on 30-pound-test line, weighed 213pounds 8 ounces.

JUST WAIT…It’ll Get Tired Captain Shawn Foster has probably spent more hours witnessing long fish fightsthan any other inshore fishing guide. In fact, he encourages them. Foster, ofCocoa Beach, Fla., gained a reputation in the mid-’90s for catering to anglerswho aim for saltwater line-class records for redfish, or red drum.

During one memorable battle in 1994 on the BananaRiver, light-tackle specialist Raleigh Werking fought a redfish on 4-pound-testline for more than five hours before Foster was able to gaff it. “That fishpulled us up and down,” recalls Foster. “Towing us around finally woreit down.”

ALL BY HIMSELF On June 3, 1973, North Carolina skipper Wade Bailey was cruising along theAtlantic coastline to deliver a new boat. Although traveling solo, Baileyrigged up a ballyhoo on his 30-pound-class outfit and let it drift back. Hedidn’t have to wait long before a blue marlin grabbed the bait. Several hourslater, still clutching the rod, Bailey climbed down from the fly bridge, threwthe engines in reverse and, as the backwash surged in, steered the exhaustedmarlin through the open tuna door and into the boat. Bailey then got on theboat radio, located the nearest marina with certified scales and took themarlin in to be weighed. The fish weighed 484½ pounds and, until 1986, was theIGFA world-record blue marlin for the 30-pound-test class.