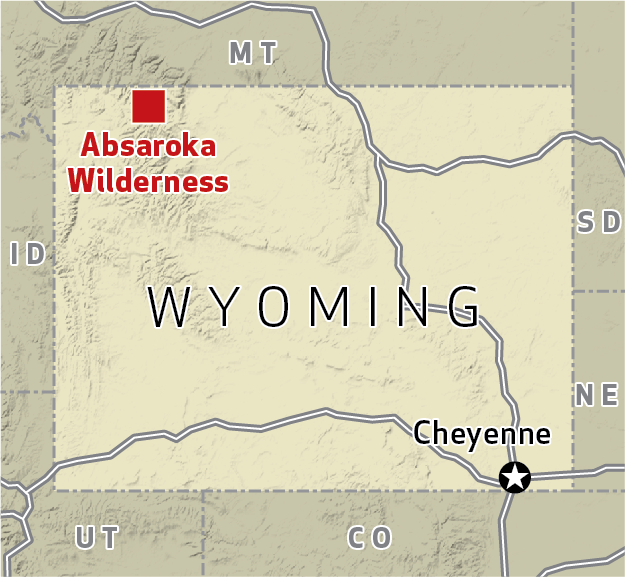

North Absaroka Wilderness, Wyoming

“We’ll base at Camp Monaco,” says Lee Livingston. The French Riviera flashes into my mind before Livingston’s High Plains drawl squelches visions of opulent casinos and bikini-optional beaches. “Up the North Fork. It was Buffalo Bill’s last hunting camp, 100 years ago this fall. He and Prince Albert of Monaco hunted elk and bear and had a big time. Lots of history back in there.”

I want to ask more about this unlikely connection between a Mediterranean principality and Wyoming’s wilderness, but Lee is fully in the present tense, pulling packsaddles off racks and barking orders to his son, Wesley. Together, they divide gear into equally weighted heaps that will be stuffed into panniers: canvas wall tent, sleeping bags and mattresses, canned food, spotting scope, rope, hammer and nails, spare horseshoes, oat pellets, peanut butter.

I throw my hunting pack into the pile to be accounted for. Lee scowls at me as he hefts it.

“We’re hunting sheep, not taking rocks back up the mountain,” Livingston growls before he moves to the corrals, cutting out the string of horses and mules that will carry us for the next 10 days and 60 miles of backcountry trail.

Lee’s reputation as a horseman is why I’m here, in his tack shed planted almost exactly between Cody, Wyo., and Yellowstone National Park’s east entrance. Equal parts endurance athlete and bucking-chute boss, Lee is a big-game outfitter, but his judgment of trophy heads doesn’t interest me as much as his skill with pack trains and wall tents. Get me into sheep country, I tell him—and myself—and I’ll do the rest.

I’ve been repeating a version of that mantra for two decades now, as I’ve applied for bighorn sheep tags around the West. Just give me a shot at a ram… But every year, I get the same terse letters back from game departments from Nevada to Montana: “Unsuccessful,” they routinely say, and I nurse my desire to hunt a curling-horned ram for another long year.

Only this year my envelope from Wyoming Game and Fish is curiously fat, and inside I find an embossed document, as ornate and richly printed as a Gilded Age stock certificate. “Unit 2A,” it says, and below my name, “Any Legal Ram.” I’m on the phone to Lee within the week.

Up The Shoshone

After hours of riding through an apocalyptic landscape of charred and blown-down trees, the stark legacy of the 1988 fire that poured over the ridge from Yellowstone Park, Camp Monaco amounts to an especially large stump overlooking the ankle-deep North Fork of the Shoshone River. Our celebrated base camp looks pretty much like the two million acres of wilderness around it.

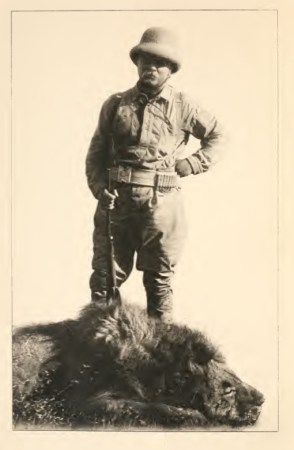

But Livingston turns out to be as capable a historian as he is a stock wrangler. That stump represents the end of an era, he says, the transition of a frontier buffalo hunter to a big-game outfitter, the violent American West reduced to a vacation destination for Europe’s royalty. This wilderness went from a landscape to be feared to one to be protected. Who knew a single stump could cast such a long shadow?

As he sets up the wall tent and pickets the horses, Lee tells the story of this place. Buffalo Bill was down on his luck, his health wrecked and his fortune depleted, relying on shopworn celebrity and land patents around the town named for—and by—him. An opportunity in 1913 to guide a European prince and a party of notables gave the old showman one last chance to occupy the limelight and newspaper headlines. It would be Buffalo Bill Cody’s last grandiose outing; he would be dead within four years.

While Prince Albert’s party was back here, someone blazed a shield on a big fir tree and then painted this backcountry graffiti: “Camp Monaco, 1913,” along with a long-clawed grizzly bear paw. That tree, and its distinctive badge, stood in this clearing and drew backcountry adventurers for decades, as the bark closed in on the blaze and time elevated Buffalo Bill to the status of Western legend. The fire of ’88 finally killed the tree.

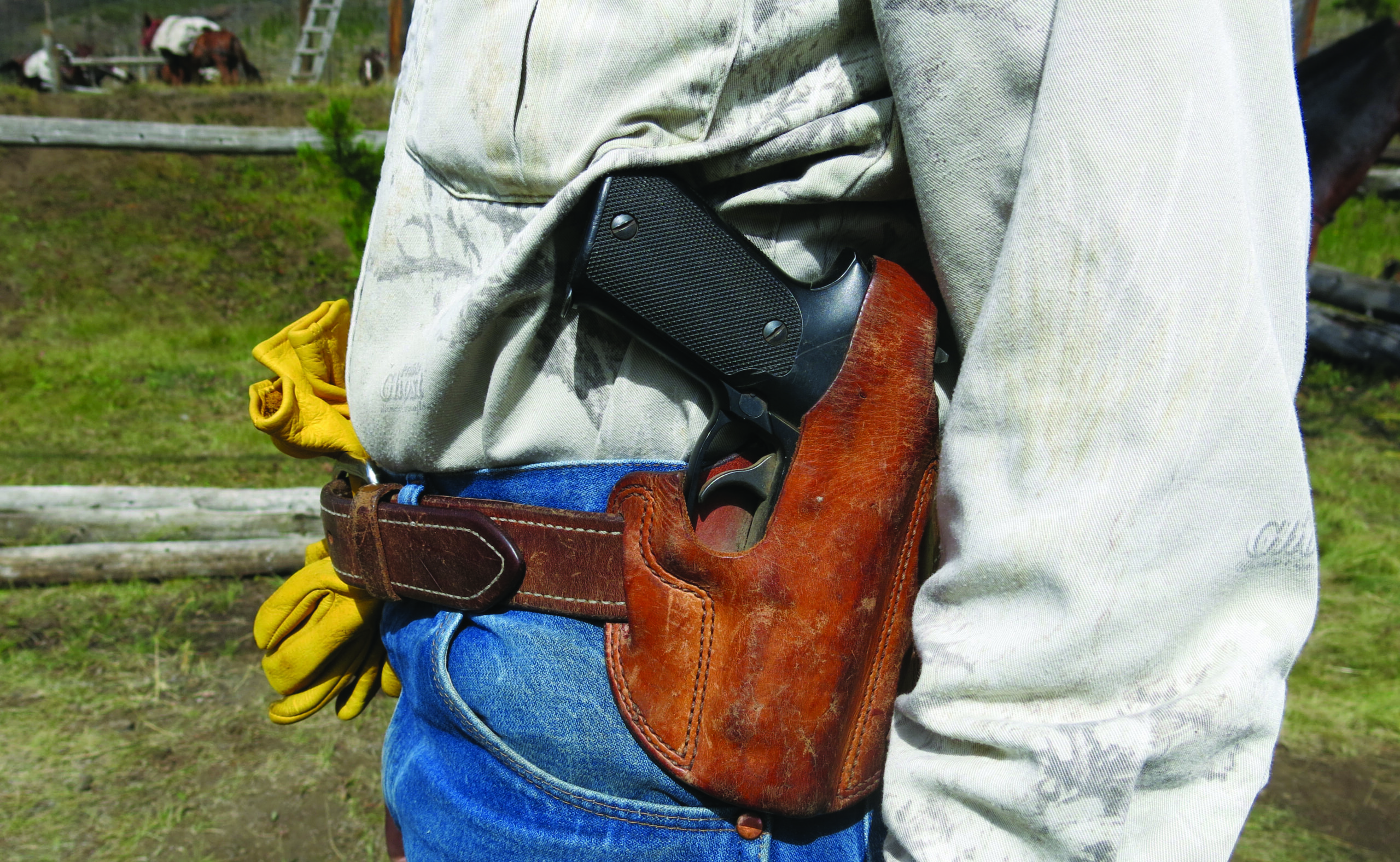

Lee is done with the tent now, and is starting supper on the wood stove. Wesley is out buckling bells to the necks of horses, so he can find them before sunup by their melodious clanging. Nobody goes anywhere in this grizzly country without a sidearm or pepper spray.

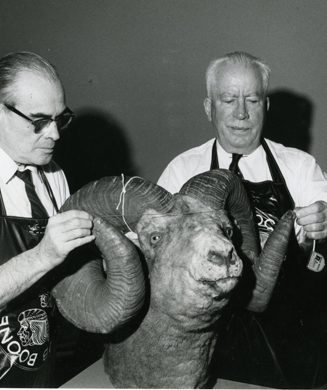

“That old tree would have fallen and rotted, but a bunch of guys in Cody decided it was worth saving,” says Lee, turning pork chops in an iron skillet. “Somebody called a helicopter. Somebody else had a chain saw. They cut out the trunk and airlifted it to Cody. It’s sitting in the Buffalo Bill Museum now, part of an exhibit about Camp Monaco. You should check it out on your way home.”

Sheep Country

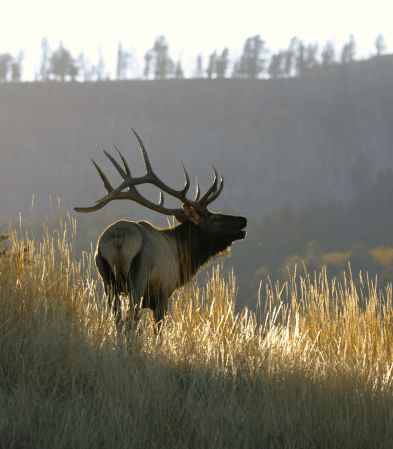

Home is on the far end of a sheep hunt, but though we’re in the heart of bighorn country, the first days aren’t especially promising. We rise before the sun and ride to high ridges so we can glass east-facing slopes. We shift our gaze to west-facing slopes in the evenings. We spot dozens of porcelain-white ewes and lambs, illuminated by the September sun, but we can’t find a mature ram.

Sheep hunting has an undeservedly romantic reputation built around final stalks and improbable shots. Ram hunters rarely disclose that 10 times as many hours are spent behind optics, tediously dissecting square miles of alpine rock, than are spent getting close to sheep.

Finally, on the third day we spot a decent ram high on a peak above Camp Monaco. He’s probably worth a closer look, but we decide to check other ridges before committing to a long, grinding climb up to him.

Backcountry hunting is all about mobility, but the value of a wall tent is that it provides a relatively comfortable base of operations. Maybe we should move camp to another drainage, I suggest. Let’s give it a couple more days, Lee says, and would I fetch some water?

By now, we’re like a small, capable family. Each of us has a role: Wesley wrangles the stock. Lee cooks and captains the camp. I get water, do the dishes, and pack lunches for our saddle bags.

I grab my S&W .44 and a 2-gallon pail and duck out of the tent into the last light of the evening. I’ll hike a half mile down the river to a little tributary that runs clear and cold. I take my time, enjoying the twilight and ruminating on the disappointing day, as I shuffle across the clearing where we picket the horses. The Camp Monaco stump is a horseshoe’s toss to my right.

Something catches my eye in the hoof-churned earth. It’s metallic. I snatch it up and scrape it with my thumb. It’s a coin. I laugh out loud. At every campsite I struck this past summer with my family, I found a penny. My windfalls became so predictable that my daughter accused me of planting coins just so I could find them and revel in the attention of discovery.

But as I knock the slag off this coin, I notice it’s different. Duller. More substantial. It’s the color of a penny but the size of a nickel. In the last glow of the evening I see the date: 1912.

I quickly slip the coin in my pocket. I don’t know what to do. It’s like I’ve seen my parents naked. I’m rattled and off-kilter and a little embarrassed. I collect the water, hardly aware of what I’m doing, and stumble back to camp somehow changed by my discovery. I’m elated and suspicious by turns. Is this a trick? Some backcountry prank that Lee pulls on first-time sheep hunters? Or could this be real, maybe Prince Albert’s nickel? Or Buffalo Bill Cody’s? Deliberately tossed off or lost from a woolen pocket a full century ago. How did it find me after all this time, after enduring wildfires and processions of hunters and a century of winters?

I don’t say a word to Lee. But to me, it’s a sign. Tomorrow will be the day.

Above The Wreckage

and the author’s sheep gun, a Forbes Rifle chambered in .30/06.

Lee must be feeling the same expectation because he suggests a change of plans. We’ll ride to a basin at the very head of the Shoshone River drainage. It’s not an area that’s known for rams, but it’s time to widen our search of this huge, alpine hunting district so at least we can eliminate the headlands from future consideration.

After miles of nocturnal riding, we dismount at sunup and pick apart the basin with our optics. I’m alarmed to see the decades-old wreckage of a small airplane shattered against a sheer headwall, looking like a moth smashed on a lampshade.

The next hours alternately flash and crawl by. We spy a lone ram bedded in a high grassy basin, high above the wreckage. Even at this distance, we know he’s mature, and killable if he stays in the basin. We ride a mile, then picket the horses in the stunted grass and make short, breathless work of another mile-long climb at 10,000 feet above sea level.

We peer into the basin, but the ram is gone. After several anxious minutes, I finally relocate him, feeding away from us in a boulder field. I spider my way within rifle range while Lee spots from a vantage point. I place a solid hit with my Forbes .30/06 and waste a second shot anchoring the ram. He’s on a slope so steep that when I finally lift his head to thank him for 20 years of persistence, the ram skids 40 feet on the loose scree and nearly gets away from me, tumbling down to the shattered airplane. I hold his head like a rodeo bulldogger and finally stop his slide.

I drag the ram to a flat spot while Lee fetches the stock, and then we carve up the carcass, loading sheep meat in packsaddle panniers and lashing the head to the back of a balky mule. While Lee tightens the lashing, I turn the secret coin over in my pocket.

Date With History

The main thing I recall about our pack off the mountain was how sure I was that it would end badly. The pack stock was bleeding with rock-cut hocks and wild-eyed with unfocused anxiety. I was sure my horse would knock loose a rock the size of a suitcase that would crush my legs. But Lee’s confidence prevailed, and we rode into Camp Monaco that evening as conquering heroes. Sure, we still had to make supper and fetch water, but everything was different. I was a sheep hunter.

Later that night, with a bellyful of ram meat and celebratory whiskey, I staggered out of the tent into the night. Up on the meat scaffold, above the reach of grizzlies, I could see my game bags heavy with mutton swinging in the mountain breeze and my ram’s horns silhouetted by the starlight. The horses’ bells played across the meadow and the Shoshone River chattered in the dark.

I stood on the Camp Monaco stump and drew the antique nickel out of my pocket. This is a gift—this place, this ram, and this experience so long anticipated but so unexpectedly complete. I balanced the coin on my thumbnail, felt its weight and its history, and flicked it up into the wild, immense night.

For more backcountry adventures, click here.