For those not indoctrinated in the cold-weather arts of hard-water fishing, tip-ups—also called ice traps, fish traps, or tilts—are mechanical strike indicators that suspend lines under the ice. When well made and properly fished, they are instruments of exquisite practicality. Each dangles a spool of line and hook (typically adorned with a minnow) beneath a small hole. When a fish strikes the bait and moves off, the submerged spool spins, tripping a small, pop-up flag above the ice. The flag signals the bite.

The rest is up to the fisherman, who rushes to the hole, sets the hook, and plays the fish by hand. If the fish is big—and many of the biggest fish of the year come through the ice—this hand-over-hand fight on water locked tight by frigid weather and accumulated snow is a primal pleasure.

We often hear that the golden age of one outdoor item or another was long ago. My father maintains that Johnson Silver Minnows were better when they were plated with real silver—as children, we were forbidden to fish with them, lest they be lost. With tip-ups, the golden age is now.

There is no sense denying the continued effectiveness of those tip-ups of yesteryear. But many have been improved upon by a new generation of craftsmen. Tip-ups found in tackle shops or via direct order from their makers today are sturdier than most of the old products, and they often have features that the old traps lacked. Moreover, a whole host of tip-ups on the market retain firm local roots, right down to manufacturers who cut or mill their hardwoods near their homes.

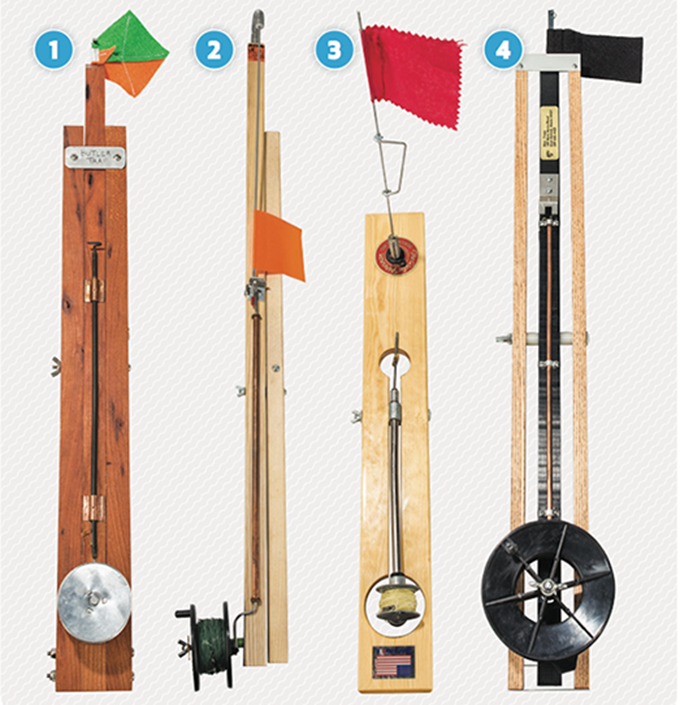

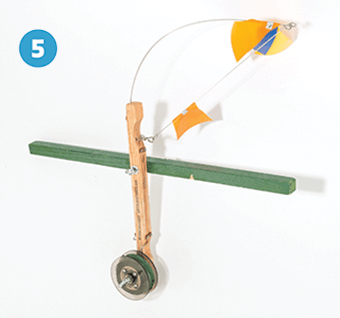

The tip-ups shown here hail from small workshops and businesses. There are differences among them. Some fold in an H-like shape, others open like an X, a design known as cross trap. One line of tip-ups—Beaver Dam (3), now sold by Uncle Josh (unclejosh.com)—is made in a rail style; these devices are built around a single wooden plank that rests across the hole, and legions of Midwestern fishermen swear by them. Rick Rand, of Little Man Traps (5; littlemantraps.com), makes traps that unfold in the shape of a Z. Some anglers will argue endlessly over the relative merits of one tip-up over another, but all of the styles shown here work.

Many tip-ups display design touches that reveal a trap-maker’s particular hand. Take Jack Traps (jacktraps.com), which possess a sturdiness and finish that rivals that of fine Mission furniture; a set of these will probably last deep into the next century—unless you back over one with your truck. Indian Hill Ice Traps (indianhillicetraps.net) are a muscular match, with heavy powder-coated spools, high-visibility flags, and a design that reduces the number of wind flags. Heritage Traps (2; heritagetraps.com) feature a simple drag on their reel, which some anglers like for keeping large baits from tripping the flag. (Jack Traps offers a clip, much like a downrigger clip, that prevents lively bait from pulling line off the spool, but retains the free-spool feature that allows a running fish to feel no resistance after the strike). Max Traps (4; maxtraps.com), offers a hybrid tip-up that mixes new technology with old. Its upright is poly UHMW and the base slats are local white ash; the poly’s water resistance prevents ice buildup at the waterline, which makes picking up and stowing the equipment at nightfall easier.

Then there is Butler Ice Fishing Traps (1; facebook.com/ButlerIceFishingTraps), made by Oliver Butler. My sons and I ordered a set of his tip-ups last year. He sent traps made from his neighbor’s aged cherry tree; it had been freshly felled and milled. These traps are unique—the grain on each is unlike any other’s, and the wood has a rich tone. Butler’s own story matches the close-to-the-earth feel his tip-ups emanate. He started making traps for sale in 2008, when he was briefly out of work during the worst of the housing slump and needed an alternate source of income. “I found a set of my great-grandfather’s old traps, and I had a set that was my father’s,” he says. “I love icefishing, and I was like, ‘What can I do to make money?'” A sideline in the trap trade followed. His design blends the features of antique traps he inherited with his own preferences. Butler Traps fold up with a snugness achievable with a carpenter’s workbench certitude. He’s sold about 800 traps so far.

Mike DeVillers, of Indian Hill Ice Traps, has manufactured about 15,000 tip-ups since he started in 1998. He does all the woodworking in his father’s barn, and the finishing work and final assembly in his basement in Worcester, Mass. “I went from 40 traps a year to 100 to 300 traps a year. Now I am doing 2,500 to 3,000 traps a year,” he says.

But the purpose here is not to rate these tip-ups. All are a testament to craftsmanship. To borrow a line from Max Traps: If you’re not catching fish, you’re in the wrong place.