The old chocolate-colored bear moved deliberately; age and experience had endowed him with caution. He also moved with purpose, intent on enjoying the donuts, grain, and syrup he had found on a little canyon-side bench. As he neared, a flicker of movement—something out of place—caught his eye. He hesitated for only seconds, then faded into the Idaho bush like a wisp of smoke. The donuts would have to wait. In the blind below, my son and I looked at each other with wide eyes. That was a huge bear.

ALONG FOR THE RIDE

I glanced at Ivan, riding in the shotgun seat of my pre-’94 Dodge Cummins as it roared north toward Idaho. He stuffed the remaining half of a hard-boiled egg into his mouth, eyes turned thoughtfully toward the road ahead. His face was pale, hardship having left a recent signature. We were en route to Table Mountain Outfitter‘s bear camp on the edge of the Frank Church River Of No Return wilderness, and my passenger, my 11 year-old, was to hunt a bear. A compact Savage rifle chambered in 6.5 Creedmoor and topped with a Bushnell Elite riflescope rested behind his seat, sighted in with Federal’s brand-new 120-grain Trophy Copper ammunition. It fit Ivan well, proof provided by tight little groups on his targets.

Barely a month earlier I had received a late-night email from Outdoor Life‘s editor-in-chief, Andrew McKean. He asked if I would be available to represent OL during a fast approaching Idaho bear hunt with the Sportsmen’s Alliance. “No way in hell,” I thought in response, glancing at my son, sleeping in his hospital bed. Swallowing a lump in my throat I went back to the email. Any other time it would be an honor. But Ivan was less than 24 hours into his new life as a Type 1 diabetic, and I would not be leaving his side anytime soon.

That’s when the light came on. I emailed Andrew back, and in a flagrant breech of etiquette asked if I could bring my son, and if he could hunt the bear. I figured that an adventure in new country would break Ivan away from the drudgery of doctors, hospitals, and checkups and hopefully turn his spirits. For five days I heard nothing. Then the phone rang, and Andrew’s voice on the other end of the line said, “Everyone is on board.”

I had to swallow another lump.

THE HUNT BEGINS

The first morning of the hunt found us standing on a mountainside while almost 30 hounds dashed excitedly around the trucks. Their enthusiasm was contagious, and I felt again why so much of the thrill of bear and lion hunting revolves around the dogs. It was Ivan’s first time among hound dogs, and he was grinning from ear-to-ear as they dashed up to him, skidded to a halt so he could rumple their ears, and then dashed away again. Scott and Angie Denny of Table Mountain tethered two dogs atop the hood of their Toyota and a handful more on the platform on top of the dog box. The other two houndsmen followed suit and the whole cavalcade divided into a cobweb of winding, steep-sided mountain roads. Veteran strike dog Lucy danced excitedly, paws kneading at the carpeted hood, nose weaving methodically back and forth across the wind, searching for the scent of a bear. Her apprentice, Charlie, hunkered down and held on, having been promoted to strike-dog-in-training just a day or two earlier.

The dogs treed a bear that morning in a canyon close to the road, a young black boar. Ivan was excited, but agreed with Angie’s suggestion that he pass on the young bear to give it an opportunity to mature. Then, surprisingly, we treed another, a small but mature chocolate-colored sow this time. I watched Ivan with interest; he wasn’t ready to shoot this bear, and I wondered if the time would come when he would be ready to shoot one.

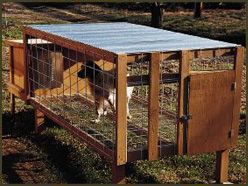

That afternoon, another one of the guides, a tall young man from Wyoming named Tyler showed Ivan and me our way to a bait setup. We popped up a blind and settled in as Tyler freshened the bait and then faded into the woods on his way back to the truck. Ivan tried hard to be vigilant, but sleep had been in short supply and he was fading fast. I told him to relax and sleep for a few minutes, and I’d keep watch. Two minutes later he was snoring.

That’s when the huge chocolate-colored bear showed up.

I could see the boar making its deliberate way up the draw, still seventy-five yards away. I calmly, then frantically tried to wake Ivan. No luck—he was out. Finally, in desperation, I pinched and twisted his cheek. His eyes opened, tried to focus, and then he grabbed his rifle and settled in for a shot, still trying to make his eyes work. The bear stepped halfway into a shooting lane at about 60 yards, but saw something he didn’t like and was gone, sneaking his way up a ravine and out of sight. We grinned huge grins at each other, whispered in shock, and waited for him to return. He never did.

WAITING FOR THE BIG CHOCOLATE

Morning of day two found us plunging into a deep, rugged canyon the likes of which Idaho is famous for. The sound of distant hounds urged us onward, eventually leading us to the tree. The bear was an average-sized chocolate boar, but Ivan elected to pass. I could tell his heart was set on the big chocolate bear from the night before.

Afternoon found us in the blind again, waiting for the chocolate boar. I had never seen Ivan so intent before, and I knew then that he would pull the trigger when the time was right. He wanted that big bear, and wanted him badly. Nightfall came, and we vainly tried to manufacture a shot at the big brown boar as he snuck through the brush above us. Then, just as darkness closed its hand over our little canyon, a big black boar stepped out of the timber. Ivan was starting to squeeze the trigger when the bear stood tall on its back legs, then dashed away into the brush. The chocolate bear had chased him off, and shooting light was gone.

Day three found us following the hounds hard after a bear that refused to tree. He would stop and fight the dogs for a moment, then run again. The bear eventually escaped across the river into the Wilderness, leaving us gathering tired dogs from all over the mountain. That afternoon we sat again in the blind, waiting for the big chocolate bear. He came, and we watched as he made his way through the timber above, never stopping, just giving us short glimpses as he moved through the trees. Patiently waiting for a standing shot didn’t pay off, as the bear disappeared into a thicket and never re-emerged. Later the big black boar from the night before stepped briefly into an opening, looked around, but was gone before Ivan could settle in for a shot. Darkness fell, and once again we crawled wearily onto our cots by 12:30 a.m.

LITTLE BEAR

Morning of day four was a repeat of the previous day’s race, the bear running hard, scattering hounds all over the mountainside, finally escaping across the river. Ivan’s demeanor was serious as he readied his gear and rifle for the afternoon hunt. I asked him if he was worried. All the other hunters had killed their bears, and Ivan said quietly “What if I don’t get one?” I told him that was possible, but even if he didn’t get one, it would be okay. He nodded in agreement but added, “I would really like to get a bear.”

Earlier that day—right after we returned from the morning hound hunt and ate lunch—Ivan had practiced making a shot on a walking bear. I tied a long string to a rolled-up sleeping pad, and one of the other hunters dragged it through the trees as I coached Ivan through making a good shot. He would dry-fire his rifle as the “bear” slid through a gap in the timber. Ivan was confident when we finished our practice session. If the big chocolate bear repeated his performance of the day before, Ivan was ready to make the challenging shot.

We hiked into the blind, hopes high that tonight would be the night. As we approached Ivan whisper-shouted, “There’s a bear!”

Was it the big one, I asked? He didn’t know; he just got a glimpse as it ran into the brush. While we set up the blind (we took it down and carried it out every night, so the bears wouldn’t ruin it) Tyler spread some “secret sauce” along the bears’ path through the timber, hoping it would stop the bear long enough for a standing shot. Ivan and I settled in for the long wait.

It turned out to be a short wait as I spotted a bear through the brush, up along the path of secret sauce. Ivan found the bear in his scope as I studied what bits and pieces I could see through the thick brush with my binocular, trying to determine if it was the big chocolate boar. It seemed too blond, and too small. I whispered as much to Ivan, and he whispered back, “Can I shoot it anyway?” I looked at him a moment, cheek glued to the riflestock, eyes bright with excitement as he watched the bear through his scope.

“It’s your hunt. He’s not one of the big ones, but you make the decision.”

“I want to shoot him,” he replied, his whisper brimming with excited hope. We watched, and it seemed forever before the bear stepped into an opening, finally offering a clear shot. “I’m going to shoot him,” Ivan said, and the bear collapsed in a heap at the sound of his shot. “Stay on him,” I whispered as Ivan racked another cartridge into the chamber, but the bear wasn’t getting up.

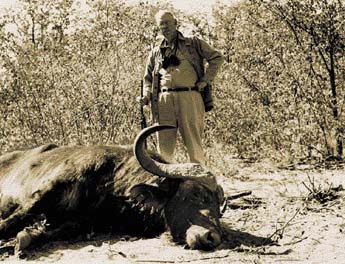

I watched Ivan, a brilliant smile the likes of which I hadn’t seen in months lighting his face. We whispered (out of habit) as we re-told the story, broke down the blind and waited for Tyler to join us. Ivan gave him a jubilant hug, and we climbed the hill to the bear. Compared to the big bears we’d been seeing, this was a little one, but it was a boar, with a beautiful blond coat. Ivan’s shot had been perfect, cleanly killing the first game animal ever taken with Federal’s new 6.5mm 120-grain Trophy Copper bullet. And his smile was perfect too, the most perfect thing I’d seen in a long time.

Read Next: The Old Dogs

As we headed the old Dodge toward home I jokingly said, “We’ll have to start calling you Little Bear!”

Ivan laughed, enjoying the reference to one of our family’s favorite children’s storybooks. “I think I want to make a bearclaw necklace,” he said. “And bear sausage with the meat, and a bearskin cape with the skin, like the mountain men wore.”

That sounded good to me.