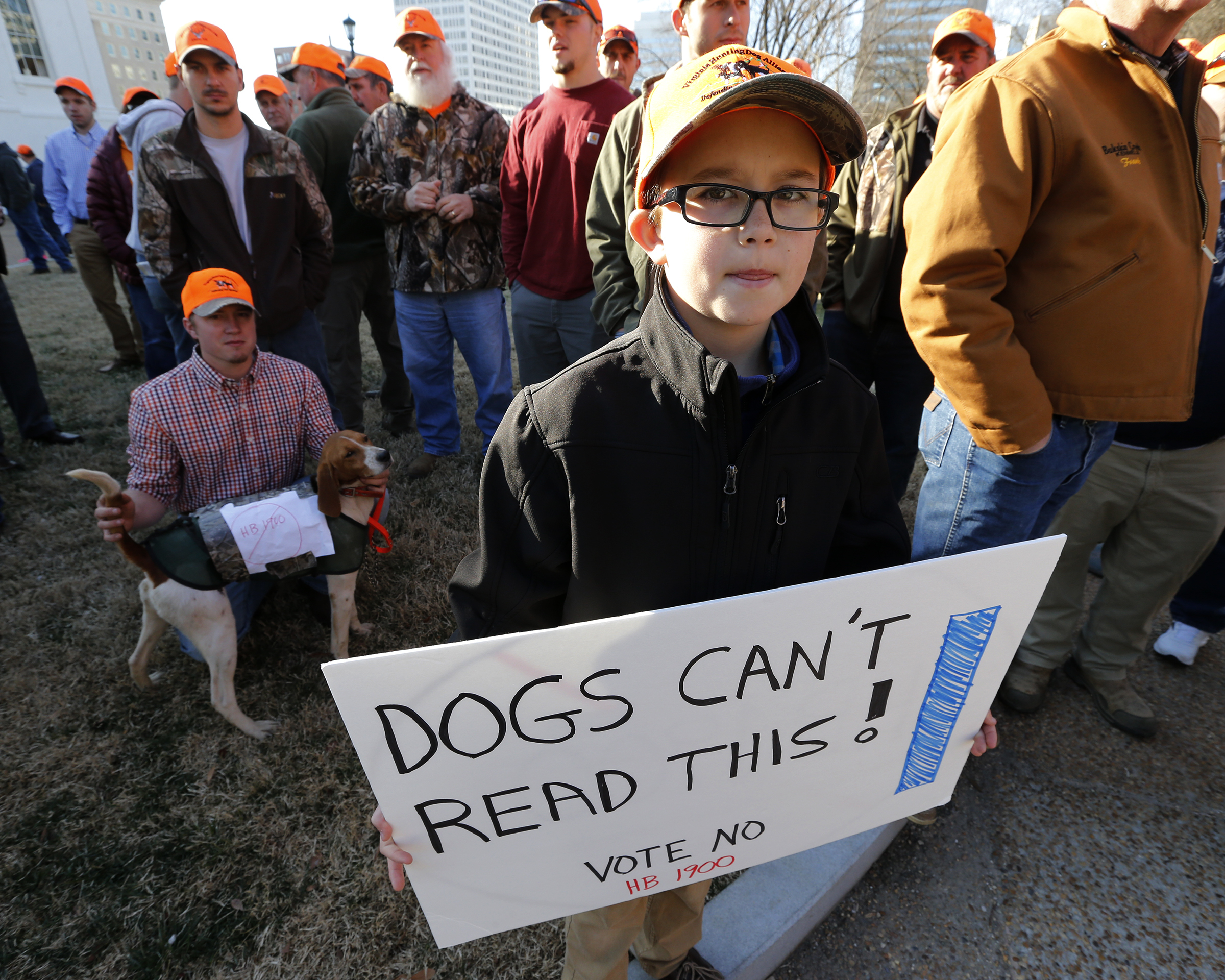

A gathering of hundreds of people in hunter-orange hats in front of a government building to protest legislation being debated inside is a sportsmen’s show of force, a statement that there are legions of hunters who both vote and care about the wildlife they pursue. But a gathering last month was different. The issue being debated inside the Virginia General Assembly pitted hunters against hunters in a dispute that is essentially a clash of cultures that defines the changing eastern half of the state.

The 150 men, women, and children standing on the still-green grass and rusty fallen leaves in January in front of the Assembly building were there to protest a bill that could be used to fine deer hunters who use dogs, which is legal in much of eastern Virginia, if their dogs run on to the property of a person who doesn’t want them there.

If a fine sounds benign to you—after all, in a lot of states a landowner can legally shoot any dog caught chasing deer on his property—the protesters would disagree with you These hunters were there to defend an age-old but increasingly controversial type of hunting, coursing deer with packs of hounds, that the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries (VDGIF) says about 55,000 state residents take part in every year.

We all know what typically happens to American traditions, especially a misunderstood one, when it runs howling into a clash with modern culture. The tradition goes extinct. This is what keeps H. Kirby Burch, CEO of the Virginia Hunting Dog Alliance (VHDA), lobbying, giving speeches, and persuading hunters to show up—wearing their distinctive hunter-orange hats—in the state capital. In this case, tradition has won the latest round, at least for now. The bill that would have criminalized dog trespass failed on a close vote last week. Supporters of the measure, which include a number of suburban landowners, vow to take the issue to the courts and to reintroduce the legislation in another session.

CHANGING VALUES

I met with Burch the night before he was to lead a rally in Richmond. He has the soft, Southern roll of the tongue found deep in the Old Dominion, a cultural leap away from northern Virginia (which basically make up the suburbs of our nation’s capital).

“The idea that dogs can trespass is ludicrous,” began Burch. “They can’t read no-trespassing signs.”

“But their owners can, right?”

“Yes,” said Burch, “and dog hunters try to stop their dogs from chasing deer onto property where they are not wanted, but that isn’t always possible. Look, deer dogs sell for a minimum of $500. The GPS tracking collars they typically wear these days are hundreds of dollars more. Owners don’t want them lost and they don’t want them killed on roads. These hunters also aren’t the rednecks they are often portrayed as. They are a cross section of society. They are almost all good, law-abiding people who enjoy the social tradition of hunting deer with dogs.”

Burch is defending a traditional pastime, a way of hunting deer in his region that can be traced back to the early days of our country. It is his lifestyle and passion. And it is under pressure.

It’s being pressured by hunters who you can’t help but have sympathy for, especially when it comes to their own property.

Take Chad Hensley, a native of western Virginia (where chasing deer with dogs is not legal) who has hunted deer for 28 years.

“I was introduced to deer dog season as soon as I moved here” to the eastern side of the state, said Hensley. “I was building my house on the 37 acres I purchased, and was attempting to bowhunt, but I gave up after one morning because of trespassing deer dogs. As I was getting down [from my stand], I heard what sounded like a dogfight. As I walked to the top of my field, I saw my new neighbor’s dogs had pinned a deer hound against a fence of mine. I quickly ran up and saved it. I and called the owner to come and get it. He thanked me and asked, ‘Have you seen the other 17?’ I knew I was in trouble then, because he was only hunting 300 acres behind me.”

“This worry proved to be all too true,” said Hensley. “I can barely hunt my 37 acres during the deer gun season. There are packs of dogs on it almost every day. And in Virginia, a hunter can go on any property without asking permission, even if they’ve been asked not to—as long as they don’t have a gun—to retrieve their dogs. This isn’t a hunting issue. It’s a property-rights issue. I am not opposed to hunting deer with dogs. I just want them to leave me alone. This legislation would simply give landowners like me a tool to curb bad behavior.”

Burch maintains that complaints from landowners about dogs on their property are pretty low. (On a statewide basis, dog-based complaints averaged 4.9 percent of all hunting complaints, with a couple of counties exceeding 20 percent, according to the VDGIF.) But he also said he gets calls all the time from landowners like Hensley who are hoping he’ll convince hunting clubs to keep deer dogs off their property. He says there are often solutions, but that finding them isn’t always easy.

Burch is polite enough not to use names, but I get the feeling he was talking about Hensley when he said, “One person from Northern Virginia recently bought something like 50 acres right in the middle of thousands of acres owned or leased by some of the biggest dog clubs in Virginia. How do you keep deer dogs off a property like that?”

Mike Hicks, a deer dog hunter and landowner of 400 acres who is backing the legislation, said, “A person who has a quarter-acre lot has the same property rights as the person who has 10,000 acres. Most clubs don’t have thousands of acres to hunt because of urban sprawl. They are typically hunting on small parcels. For smaller properties, short-legged beagles or bird dogs, like I use, make more sense. As responsible dog hunters, we should be using the best tool for the job.”

INCOMPATIBLE HUNTING STYLES?

Such is the conflict occurring in areas of the South where hunting deer with dogs is legal. But before we dig deeper into both sides of this controversy, put yourself in both sides’ hunting boots for a moment.

Do you know a hunter—even one—who wouldn’t like to experience the beating cacophony of hounds in pursuit of game amidst the camaraderie of a big orchestrated hunt with friends and friends of friends all gathered together in the autumn forest? Can you imagine your pulse beating as the hounds come through the woods toward you and can you feel the cold sweat in your palms and on your fingers touching gunmetal as you tell yourself to shoot well? This is the experience William Faulkner knew and brought to life in his classic tome Big Woods.

Alternately, imagine yourself in a treestand on your own land. All around you is the lovely reverie of opening day. It’s Christmas morning for a deer hunter. But then you hear hounds coming across your land. There is the same music of hounds on a hot track and the feeling of cold sweat on your palms, but now for an entirely different, even sickening, reason. Those dogs are chasing the deer you’re hunting.

Those two real feelings, two realities in opposition, are causing this battle among deer hunters that is occurring in areas of the South, such as in eastern Virginia. This is why some are trying to solve conflicts with legislation.

HEART OF A TRADITION

Besides Virginia, eight other states in the South (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, and South Carolina) allow deer hunting with dogs in some areas. A nationwide survey in 2008 conducted by the VDGIF “found that 70 percent of the states with deer dog hunting reported that problems between landowners and hound-hunters (of any game) were a serious concern; only 6 percent of the states that do not allow deer hunting with dogs (but allow other forms of hunting with hounds) indicated serious concerns with this issue.” So bear and cougar hunting with hounds, and even the increasingly popular coyote hunting with hounds, does not seem to be causing the same level of conflicts.

“Actually, our biggest public-relations problem is that in deer season, people will see hunters in orange standing along public roadways,” said Burch. “These guys don’t have guns. They are blockers positioned to grab dogs that might run into a road or into private property. People see these guys with coolers in the back their trucks and assume they have beers. But really, all they have is water for their dogs.”

This style of hunting can certainly be very visible. It isn’t like rabbit hunting with beagles, where, hunters will often take stands and wait for the rabbit to circle back. Whereas, with most deer hunts with dogs, hunters surround a property. Dogs are then released into one side of the land. The dogs get the deer up and chase them—maybe out of thick cutover or swamps. The standers, who typically use shotguns loaded with buckshot, might be in a treestand or on the ground along trails. They shoot deer as they flush out of the cover. They are then supposed to grab the dogs, but that isn’t always possible.

The VDGIF looked at available research and found that “the average deer chase lasted 11 to 33 minutes and extended 0.8 to 2.4 miles. Historically, hound hunts for deer took place on farms with contiguous areas in excess of 20,000 acres. Today, most deer clubs have access, through ownership, leases, or informal agreements, to areas 1,000 to 5,000 acres in size, much of which is fragmented.”

This is why landowners who have small acreages east of the “dog line” in Virginia might at times be overrun by deer-coursing dogs.

A report by the VDGIF noted that “[c]hanging land uses, demographics, and societal attitudes are exerting pressures on the sport not seen a generation ago.” This is because the human population of Virginia has been growing at a rate of 1.4 percent each year since 1960. There are now more than 8 million people in the state. Much of this growth has been in Northern Virginia, but the VDGIF says “some high-growth urban and suburban areas are open to deer hunting with dogs (e.g., Richmond, Hampton Roads).”

Also, between 1959 and 2012 in Virginia, the total farmland acreage and the total number of farms have decreased by 36 and 54 percent, respectively, according to the VDGIF. In 1959, more than half (52 percent) of Virginia’s land area was farmland, compared to only 33 percent in 2012.

THE LEGAL LANDSCAPE

The legislation introduced in Virginia, which failed Feb. 6 on a 47 to 48 vote, would have imposed a $100 fine for the first occurrence and $250 for a second incident, on any hunter whose dogs run on a property where the owner has given notice “in writing or by placing signs prohibiting dogs where the signs may reasonably be seen.” The money would go to help local governments with animal control.

Landowners like Hensley say this is just a tool to help landowners prosecute the few bad actors who knowingly let their dogs go in places where they are bound to run across private property where they are not wanted.

But Burch said, “I have no redeeming graces for the bill. It is a bill to do harm because someone has an agenda.” Burch feels it would pit neighbor against neighbor and that it would unfairly penalize hunters whose dogs inadvertently cross a property line in pursuit of deer.

When asked if this legislation is being pushed by people moving into areas that traditionally allow this practice, Burch said, “No. It is mostly being pushed, state by state, by a couple of big-money groups with agendas.”

John M. Morse, Jr., chairman of the VHDA, outlined this fear on Facebook. He wrote:

Many of you may already be aware of at least 2 groups formed on Facebook, whose goal appears to be to outlaw deer hunting with dogs or failing that at least repeal or modify the “Right to Retrieve Law”’…. These groups are Virginia Landowners and Virginia Whitetail Deer Fair Chase Hunters. We have learned this group held a meeting with a high dollar/high influence lobbying firm on 1/3/15. The amount of money required to retain this firm should cause all of us alarm.

The reason for attacking hound hunters is the same; to make commercial hunting and deer farming practical in Virginia as they have done in Texas, Florida, and South Carolina. The four steps necessary for them to make money in any order are:

1) Make Sunday Hunting legal (This has been accomplished)

2) Make baiting legal

3) Outlaw deer hunting with dogs

4) State Regulation of Commercial hunting outfitters and Guides

Burch told me, “They want to form big commercial hunting operations with Texas-style feeders for deer, but they don’t want to pay to high-fence their properties. To do that, they need to get rid of deer hunters who use dogs.”

The VHDA actually lobbied to make it a misdemeanor for a hunter to intentionally release dogs on another person’s land so they can hunt without the consent of the landowner. This law passed, but Burch notes that it has not been enforced. People like Hensley, however, point out that finding a pack of dogs on your property is not enough evidence to prove the intentional release of those animals. “It has not been enforced because it’s impossible to enforce,” he said.

“The problem,” said Hensley, “is a hunter can release his dogs on a 100-acre section he has access to knowing full well the dogs will run onto adjoining private property and you can’t stop or punish him according to current law, which is why this [new] legislation is necessary.”

Some states, such as Georgia and Florida, have minimum acreages that a hunter must have access to before he can release deer dogs. That isn’t the case in Virginia. In fact, the VHDA has a “Hunting Dog Owner’s Code of Ethics” on its website, which says hunters should only release dogs on property they own or have access to, but it doesn’t stipulate a property size or mandate any intent for hunters to keep dogs on property they are allowed on.

Meanwhile, Virginia is unique in that if a hunting dog strays onto another person’s property, the hunter has the legal right to retrieve the animal even if the hunter has been previously asked not to trespass. According to a report by the VDGIF: “Virginia appears to be one of only two states where hunters can lawfully retrieve dogs even when access has been expressly denied by the landowner. In Minnesota, the other state with a similar dog-retrieval law, dogs cannot be used to hunt deer.”

Some landowners, such as Donald Wright, a landowner in the town of Virgilina, in Halifax County, have called Virginia’s “right to retrieve” law unconstitutional.

Other states use different regulations to alleviate problems.

Alabama law, for example, prohibits the release of deer hunting dogs from public roads or rights-of-way without permission of adjacent landowners. Louisiana law specifies that it is unlawful to “stand, loiter, hunt, or shoot” game from a public road or right-of-way. Other Southeastern states, such as Arkansas, Florida, and Mississippi have statewide prohibitions on hunting from or near public roadways. Virginia and North Carolina have varying state and local laws regarding road hunting.

Also, to encourage deer hunters to keep dogs on properties where they have permission, Alabama, Georgia, and Florida have developed permit or registration systems to increase accountability of deer hunters using dogs. Permit systems for deer hunting with dogs were developed after other approaches failed.

THE FUTURE OF DEER COURSING

The number of hunters who chase deer with dogs has been shrinking for generations. It requires a lot of room, so it has been dwindling with the decline of an agrarian society and the growth of suburbs.

On the upside, Kirby Burch points to the communal aspects of hunting deer with dogs. “It can be hard to get a youngster to sit for hours in a stand on a cold day,” said Burch. “But take him out with his father and maybe mother, uncles, and grandfather to have this big, active experience and you’ve hooked him for life. That’s why this social type of deer hunting is still so popular in Virginia. It is a powerful way to include the next generation and to teach them to be upstanding adults.”

Of course, there is a lot more to this story. There is now a case in the courts in Virginia in which a person who uses dogs for deer hunting allegedly stabbed a landowner during an argument. While the victim survived, and it isn’t clear if the alleged attack was over trespass issues related to hunting dogs, it has been used a lot as an example of how bad these conflicts can get. There are other cases of landowners allegedly killing or wounding hunting dogs. Burch mentioned a “Navy SEAL” who allegedly “killed three hunting dogs” recently. He said this person is “guilty of three felonies.”

Virginia’s dog-trespass bill has been voted down and is unlikely to come back in another version before the Assembly adjourns Feb. 25. Proponents, who argue a trespass law would give landowners a tool to stop bad behavior by a few, may seek a court ruling that revolves around property rights. Opponents of the legislation see it as another attack on the age-old tradition of chasing deer with hounds. But no hunter interviewed said they want deer hunting with dogs banned in Virginia. All sides seem eager for a compromise so they can enjoy their land and their cherished methods of hunting deer.